Zooming In and Out

Tongji Philip Qian

→MFA PR 2020

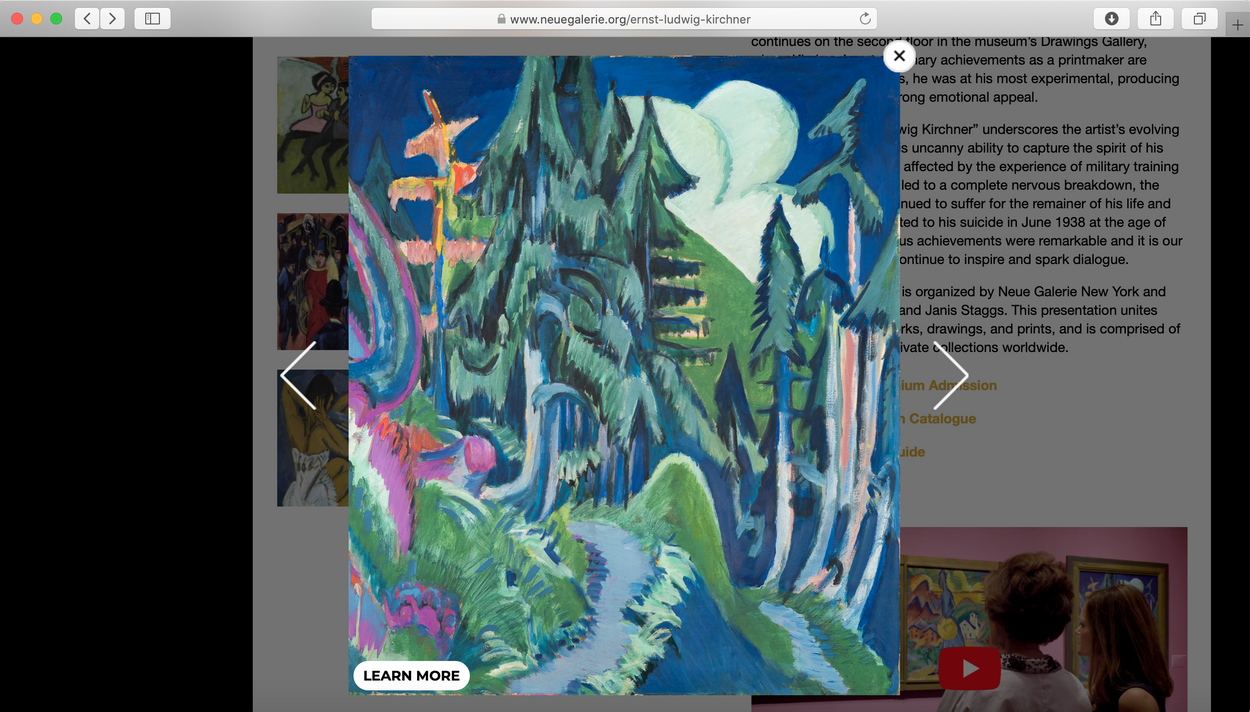

Ernst Ludwig Kirchner painting on the Neue Galerie website. Screenshot by the author.

Ernst Ludwig Kirchner painting on the Neue Galerie website. Screenshot by the author.I once discussed with a curator the nature of being an artist and a critic, and we thought the difference lies in the definition of an artistic practice and a creative one. Art might rely on a physical studio, whereas creativity does not. Also, studio visits happen frequently for artists, but critics rarely stay in their space to be critiqued. Improvement, although faint in both cases and sensible at best after-the-fact, is more desired and treasured for artists. Critics are relatively exempt from critique; as long as they believe what they say and stand by it, their view flies, no matter how turgid or off-base their prose may be.

This was the debate that preoccupied me for the past two years as I developed my thesis. But things have changed. Under the peculiar social and political environments brought forth by the coronavirus, such discussions become irrelevant. They are not essential. They do little to combat against the virus and the dreadful deterioration of humanity. As people celebrate styles of social distancing at Prospect Park in Brooklyn and appreciate the artistry embedded in hand-made masks, are we taking this moment seriously enough? The pandemic is not yet a rupture—as this term implies an eventual return to the norm—and it is far from historical, as we are still in it.

But let’s look ahead. It will be a privilege, in some way, to come out of this troubling time. Ernst Ludwig Kirchner did. He survived World War I and the Spanish Flu, and managed to continue his painting and printmaking endeavors. Such global events, however, left irreducible marks on his mind, which crystalized in renewed subject matters and color palettes. He no longer showed desire to wander the streets of Berlin, painting flamboyant prostitutes, but instead moved to the bucolic Swiss mountain town of Davos to ameliorate his trauma. Urban scenes departed, and natural scenery entered his canvas. Kirchner’s uncanny life events paralleled his miraculously painted psychological landscapes, and his suicide at the age of fifty-eight left a tremendous artistic “package”—one with an undeniable accent of tragedy and, of course, a profound story.

It is curious to notice how artistic information becomes accessible during this pandemic. Museums open and expand their virtual collections for free, and conversations with curators and critics, because of Zoom, have never been so easy. Museums are no longer ceremonial spaces due to the ambiguous demarcation of their boundaries. New York City might not be as charming a place to live anymore, because the whole world shares access to its vibrant art collection.

As physical travel gives way to psychological deriving, one thing stays the same. It is the power of a story. Numerous Kirchner paintings across the globe can be viewed online, but the story is ever more robust because we can suddenly feel his struggle. His world becomes closer to ours now, and his use of the color pink to outline forests no longer bothers us. Instead, it gives us pleasure. In this sense, art-historical, third-person narration joins forces with our first-person perspective, and we are granted immediate access to his story, only to compare it with our own. It is like wearing a pair of Kirchner glasses—we start to steal the cigarette from the dancers in Berlin and slide down the blue slopes in the Swiss Alps. Fiction and reality begin to merge, and one day it becomes zeitgeist.

In my first art history class in college, I learned not to use the word “interesting.” It is vague, ephemeral, and even ethereal. But I kind of like it now, because we live in an interesting time.