Driftwood

Sabie Bellew

→BFA IL 2022

“A weary soul collects his final years ashore, alone but for cracked shells and other broken things. A weathered face burnt by wind, salt-stained eyes and salt-stained boots sagging half asleep. Just as breathing waves put the greatest stone to sand, so too the gentle knock of endless tides work their solemn will upon the life of man. Silent tales of years at sea ever slipped soft and easy from those cracked lips. Perhaps his words were but a trembling white fist, all bone and years clasped about tattered memories long come to dust, a silent prayer to gods long dead. Awash with day’s dying red ember I sat close upon his driftwood bench; smooth and white, it twisted in feral elegance like some huge old bone carried far from home. There I listened to his words.”

– Driftwood by Blacksole Cryston, Tales of Land and Sea, 1293 A.T.

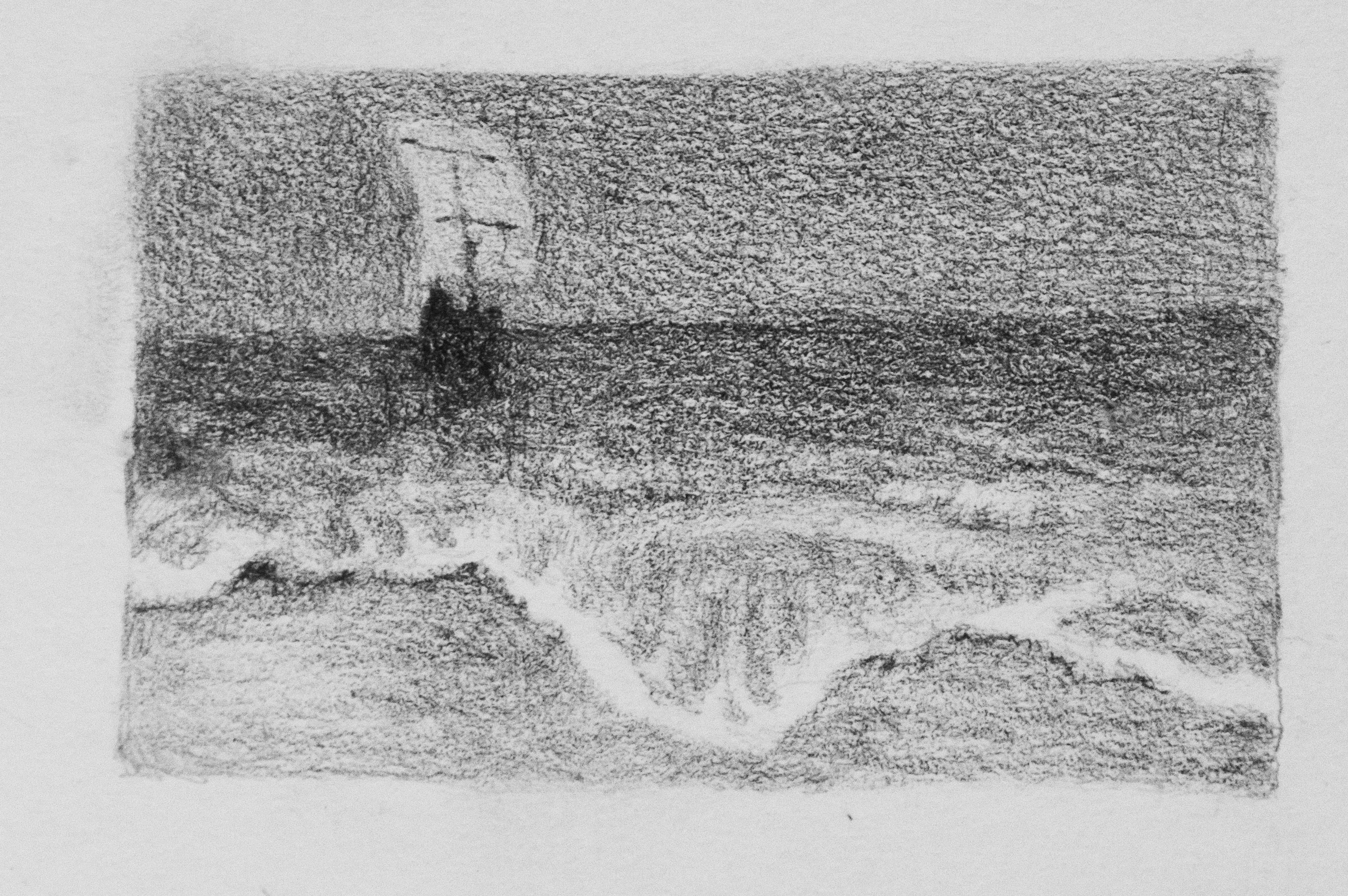

Save for digging clams and chasing crabs, there had been little to occupy either Ulfyn’s mind or time over the past two weeks. Distractions were necessary—they kept those memories of what had happened somewhere deep where they could not hurt him. So he paced the beach. To his left, shrubs and bushes gave way to a thin piney forest too small for a name. To his right, the sea yawned on forever. At low tide this part of the beach would stretch most of a mile, the sky and shore forming a mottled grey mass punctuated by a spackling of white seabirds and black rocks. The fine sand felt good between his toes, despite the cold. The air was chilly too, though a strange warmth in the southern breeze told of spring’s end. He tried to focus on pressing his weight slowly into the ground, feeling how it forced the sodden grains upward between his toes. He looked around to see if anyone was coming—it was not safe to stay here, but where else could he go? He turned his gaze downward; the sight of the deep sea still set feverish rushes of panic through his bones if he stared too long, though not half so bad as when he was away from open water altogether. He pushed the thought away, concentrating on the feeling of displaced sandspiders wriggling under his feet and scurrying about the ankles. Some crawled under his damp and sandy linen breeches, others had made their home amongst the overgrown mess of tangles and burrs that had become his beard and hair. Their bites itched fiercely, though it was nigh unavoidable on the east coast. Already it was noon, and the promise of naked steel pressed on his mind.

Two weeks past, Ulf had been squatting on Heryn’s porch, gutting fish for dinner when Reynard arrived. Thin and pimpled, with only seven and ten years to his name, Reynard had approached the coastal village sat upon an old garron. He wore rusty mail over an ill-fitting shirt of boiled leather, the splintered and faded sigil of house Lidden barely visible upon a small wooden shield strapped to his back. Around his neck was tied a stained and tattered handkerchief. The only exception to his meager raiment was the finely tooled leather scabbard that hung from his belt, engraved with delicate floral patterns inlaid with silver and onyx petals. His sand-colored hair fell straight and greasy over round shoulders, framing a narrow face with sharp, handsome features upon which a wispy mustache was struggling into existence.

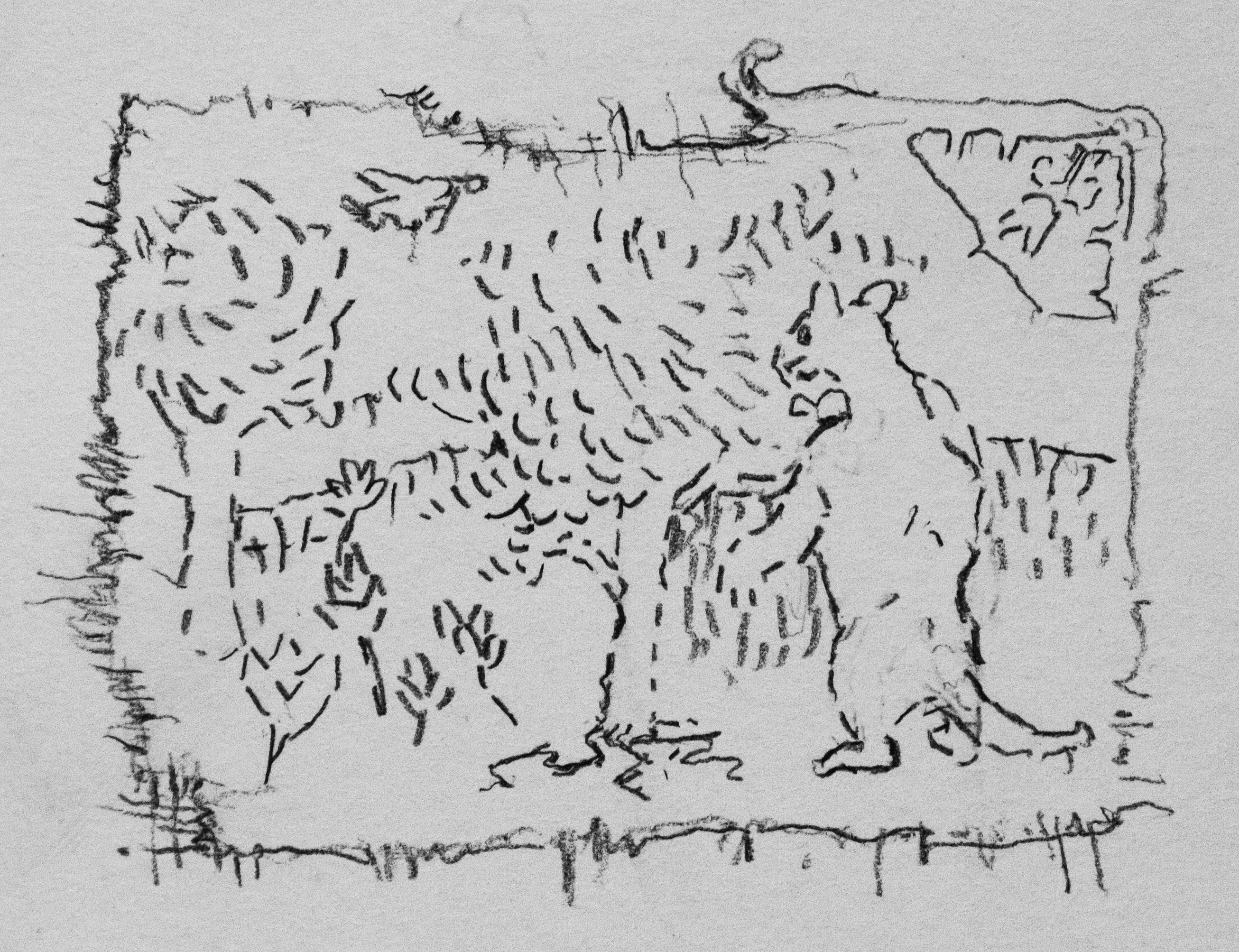

He had changed so much that it took Ulfyn a long moment to recognize his childhood companion. Reynard was no longer the twitchy kid who would squat over tidepools with Ulf in search of strange slimy creatures when his father came collecting levies. Back then Reynard would ride all day just for a walk with Ulfyn’s younger sister Ysmay, and even wore her favour for a local squire’s turney when they were only four and ten. It was a white cloth with uneven patterns of trees, sheep, and ratbears reaching for leaves, done in coarse brown thread. She had kept it since before she could walk. His overwrought performance of highborn gallantries as the tourney drew near grated on everyone, save for Ysmay, who found it all hilarious. He and Ulfyn trained with wooden swords amongst trees that peered over the coast. Despite being almost twice as old as Reynard, they both left bruised and limping when the day was done.

No, this man had put many long leagues between himself and that boy. He shot a cold glance at Ulf and rode on as a stranger might, grey-green eyes betraying no sign of recognition. Does he remember me? It made Ulf think of a poem his mother would recite, a line when she felt the weight of years upon her: “Just as breathing waves put the greatest stone to sand, so too the gentle knock of endless tides work their solemn will upon the life of man.” He returned to gutting fish, ate with his sister and her kids, and fell upon a bed of loosely bound straw by the main door as dark filled the sky.

Before dawn had broken on the next day he was ripped from sleep by two pairs of thick arms wrapping about his limbs in the dark. Panic sent dread-strength through his body. Writhing, he tried to scream but his mouth was smothered by a huge sweaty palm, caked with calluses. He bit, unthinking, mouth filling with the taste of blood, cockles, and salt. The hand twisted away with a grunt, though by that time they were already moving.

Next he was upon the shore, bound at hand and ankle by frayed rope. The first light of day spilled across dozens of familiar faces sat upon stumps and driftwood logs in a wide circle around him. Reynard stood ahead, pacing in tight circles as idle conversations conceded to a drifting hush.

“Forgive me for the harsh awakening old friend, I thought it would be best to settle this confusion with haste, lest we keep these fine folk from their day’s toil.” He did not wait for a response. “The tales have travelled as far as Hayford, each wilder than the last. Lady Cassandra bid me see to these rumors, bring justice if need be.” His fingers ran casually across the hilt of his sword. “Rumors, however, can be fickle. I would hear the truth from your own lips and those of whoever might … cast light upon this strange tale. So, dear Ulfyn, just what exactly transpired on your last voyage?”

Ulf breathed deep, praying the words might flow from him sound and even. “Twelve moons past we set sail for Spider Isle, me and eleven others. The pilgrim hills passed Tenfowl a while ago so we thought to trade sweetwater to the bug eaters, now that the well is good, and fish oil too. It’s not so bad as they say up there, if you keep good company.” He could tell his voice sounded shaky and strained. From only a few words his tongue had turned stiff as salt cod, his throat a dry rasp. Yet he pressed on. “Then we were to sail east to the deep sea, hoping the summer wind might take us to Seastone in ten days rather than twenty. Then we would come back. A five-week round trip.”

“Yet six and thirty came and went before you returned. Alone.” A deep voice called out from across the circle. Before Ulf could reply, the woman beside him addressed the gathering.

“He returns nude and filthy, hardly more than bones stretched with skin, all wide-eyed and gaping like some fish! His sister is a kind soul to look after the broken thing for so long, but three moons have turned and we are no closer to knowing what happened to those men. What became of our brothers, our husbands, our sons?” A quiver in her voice threatened tears. “Where is my son? What became of Donnel? I say Ulfyn lost his mind at sea. Wouldn't be the first time either, we’ve all heard the tales. Killed my boy, him and the rest I say.” A fog of murmurs lifted from the beach. Ser Reynard turned to Ulfyn.

Kneeled over on the beach, his head swam. “What had happened to the others? I was no better than any man on that ship,” he thought. “Why did I survive while they died? Maybe I did kill them, went mad at sea just like she said. Maybe my head would mean justice for those families.” Sensing the press of silence, he tried to choke out a reply but his chest clenched the words before they could escape.

“Guilt holds his tongue, Ser,” said the woman.

“Then it would seem I have no choice,” said Reynard, drawing his sword. “I am sorry. Though might be this is a mercy, from the look of it.”

Before he could fully comprehend the situation Ulfyn was pressed to the sand. So this is it. For some reason he felt no panic now. All he could think about was Reynard. How he had changed. “Mercy,” he thought. The contempt in the knights' words were nothing more than a thin scab over palpable fear and sadness. Reynard had come knowing he might kill me, perhaps wanting to, for lady Cassandra. Maybe the fool thought his Lady might reward him with that lordless ruin, Tenfowl Tower. To think it would be the broken lover who had stayed beside Ysmay to the very end, giving whatever small comfort he could as he watched sweetrot devour his first love from the inside out. The kid who stood watch all night as her body disappeared into the black sea. Pride had not eased his tears then, but it did now. Might be he never wants to know such pain again. Someone wrapped a strip of cloth tightly around Ulf’s eyes and ears, such that the world sounded muffled and distant. He had felt brave for being so calm in the face of death. The execution was taking longer than he had expected, and certain animal instincts were waking from their dormancy. From somewhere behind him, Ulfyn heard furious shouting in a familiar voice. By the way Heryn’s shouts swelled, it was clear she was sprinting in a red rage, shouting about people breaking her door and waking her kids and trying to steal her brother and shame on you. A brassy bang rang out like a struck pot followed by curses and more yelling from Ser Reynard. Ulfyn heard her say something about a storm and how “he cooks and helps keep the house orderly.” After only a few moments, it seemed tensions began to ease by the muffled arguing receding from legibility. The cloth was unraveled to reveal anger and discontent etched upon every face about him. Ser Reynard spoke first, frowning. “The matter of your innocence has been called back into question, it would seem.” Reynard’s eyes scanned the ground by his left boot which twisted back and forth to form a small hole in the sand. “Perhaps the gods have seen fit to spare you another day.” A low rumble flushed the encircling townspeople. He brought his eyes forward to Ulfyn. “Though you ought to thank your sister. Were it not for the respect I bear her, the spiders would already be gorging upon your life's blood. I will grant you a fortnight. Should you be found here or on any land held by house Lidden come dawn of the fourteenth day, you will not see dusk. This, I swear by my honor as a Knight.”

He had survived that day, but the threat of retribution was far too great to bring upon his sister or her family.

And so he left, but not truly. Sleeping among sandbanks and tall grass, living on clams, barnacles, and blackberries for thirteen days, he had been cast to the shore like an old net. More often than not his death seemed a small thing next to leaving this coast. This may be my last day. He had known this would come, but only now the weight of it filled him, buried him. He realized he may never see another summer, so he recalled one from years long past: a boy of no more than twelve, he would play with his sisters in the shade under his squat two room home in Saltbank, only a few miles from where he stood now. He and Heryn would pretend the stilts holding it up were trees in the Renholt, the cursed forest island where rain never ceased and few who entered ever returned. The creaky footsteps of his parents above were demons hiding in the canopy, waiting to swoop down and eat them. Ysmay would slap her tiny hands in the sand and laugh, or get it in her mouth and cry. Back then little Reynard would follow him and Heryn everywhere, squeaking out half-remembered ribald jokes he hardly understood and laughing too loud.

How the sun would blaze. He remembered how bright the red of his father’s back would be when he would return from days at sea. How it peeled off in huge strips throughout the week.

“Like a crab,” Heryn would whisper to him at night with a grin he could hear in her voice. “That’s how he got so big,” his mother confirmed the next morning. “New skin means a chance to be stronger than who you were yesterday.” Later that day he stood sweltering beside his father at the base of a shallow dune, the stiff grass poking through the sand pricked his calves. On a regular day, he would not mind, but it was not a regular day. Facing the ocean, he could only see the top half of their boat above the colossal mounds of seaweed. The green mass seeped an air so foul it could buckle the knees of even a seasoned seaman, should he be caught unprepared by an unfortunate turn of the wind. The breath of the deep, the locals call it. Though the tides of time had washed away his father’s features and the sound of his voice, his words remained.

“Tarry not Ulf. We’ve fish to catch.”

When his legs refused to move, his father had crouched beside him, speaking softly. “Do not be afraid. Today is a gift. You will learn what it is to shed your own blood for a world that will thank you not. What it is to care. That is all we have when the sun sets on our life and all we can offer to the lives that come after. I know you can do it. I’ll be right by your side the whole time. I promise.” He rose, giving Ulfyn a pat firm enough to send him stumbling forward. Turned pale, almost grey, from weeks of relentless beating by a midsummer sun, the piles of sea sludge teemed with such a density of sandspiders that one could be forgiven for thinking it was boiling. The only way to their boat was through. He remembered being afraid, remembered the terrible crunching first step as his leg punctured the seaweed’s membrane. The hot, fetid stench that followed had hit like a warhammer. Even his father had wretched. Reeling, he watched his skin come alive as an angry carpet of sandspiders scrambled over him, fighting for purchase on any scrap of exposed flesh. They had spent most of the day tearing bloated red sandspiders from each other and tossing them in a slitted holding basket lined with shark oil to be used as bait through the week. It had been a hard day, but even so, memory brought Ulfyn a momentary stillness. A blissful respite from the constant threat, the ever-encroaching inward spiral of consciousness clawing at every moment of idle thought. His father had been beside him on that day just as he had promised, had done the same when he was young. Their legs appeared as chewed meat for weeks to come, and itched for months. When they returned, though, the seaweed was largely gone, picked and nibbled by the new generation of sandspiders and pecked flat by seabirds looking to sup on the bugs. For a moment, Ulfyn felt almost normal again.

The peace did not last long. A steady beating rose from behind, a horse pounding the sand. Ser Reynard had come, as promised, he thought. The bites on his ankles itched fiercely, but he knew what had to be done. Then he noticed the rider’s sword winking in the sun, drawn to the side as if he were charging into battle.

That is not good, he thought. Not what I was expecting. As the garron thundered forward, Ulfyn broke into a sprint, scrambling up the dunes through brambles and shrubs until the treeline was in view. Hooves tore through sand and roots behind him, plate mail shifted over the horse’s quaking back only feet away. Cold steel whistled as he dove past a tree. It found purchase with a sickening thunk. Ulf shot to his feet, turning to see a cursing Reynard sprawled across the dirt, his sword lodged two inches deep into the flesh of a pine, the horse blithely galloping into the forest.

“You need not kill me,” Ulf panted as the knight gained his footing.

Reynard paused as he tugged the sword free. “Of course I do.” he replied with a grunt, dislodging it from the tree. “I swore on my honor. Tell me, what use would lady Cassandra have for a knight who cannot keep his word? I cannot be useless. I will not. No longer.”

“Your vows are to uphold justice, yes? What justice will you bring by cutting me down?“

“Peace to those families, Ulf. Vengeance. Tell me true, did you kill those men?

“I don't think so. Something bad happened out there, Reynard. Beyond myself, I think.”

“And what cause do I have to believe you?”

“Why would you ask?”

They stood silent for a long time until Ulfyn drew forward to stand before Ser Reynard. He laid his left hand upon the sword and with a sharp inhale pulled a streak of bright blood across its length as Reynard looked on in shock. “Show them this sword. Tell them you slew me, buried me at sea. We are not far from Snakespine river. Once I cross there I will be on Barlowe lands. I shan't return. This I promise.”

“How do I know you won’t come back?” Reynard asked.

Ulf felt a bit faint. Blood was pulsing from his hand, thick and black. His eyes met Reynard’s.

“I swear it by Ysmay’s bones, Ser.” They looked into each other for a time. Wordlessly, the young knight undid the old handkerchief about his neck and wrapped it tight around Ulfyn’s hand, the brown threading disappearing as it grew dark and heavy with blood. Reynard’s arms folded around Ulfyn, the lobstered steel gauntlet and couter pressing cold against his tunic, Ulfyn returned the embrace.

“I could not save her with this favor,” Reynard said in a voice that shuddered. “Perhaps it will stop the blood.” They broke apart, each nodding a silent goodbye. Ulfyn turned, then, making for the stream.

“Should thee wake past yond where winds bite bitter clean through cloth and stem, past black waves bent ever by profaned muscle, seen flushed furious by their crowns of spit; land a fading dream, the night sees a soul sink into a deeper kind of sea. Past here gapes the end of our world, a maw that chews upon the careful seam of sea and sky, gnash and grinds 'til only glass stretches ever far from home, here find reflection loose in meaning. Aye, black and endless is that water for black and endless be the secrets kept below. ‘Neath these waters the lonesome kraken dwells. This I know.

Not those to rend a cog in warm westerly oceans, but something aged past the breadth of time, an endless quickening in the wet. In the depths this creature waits, for what I cannot say. But in its bowels a sadness 'ever stirs. Grief has filled the inky deep, unruptured by light nor sound. A despair subtle and severe holds fast, such as man cannot know. So old are these beasts, so alone, they wept till oceans rose from salty tears, then seas and lakes and stream, so evermore could their cascading melancholy hew mountains with its flow. Here they built their bed of sorrow, endlessly muttering silent songs to the void, no ear to cross save mine. There they were and there they stay, humming blindly in their dark.”

– Driftwood by Blacksole Cryston, Tales of Land and Sea, 1293 A.T.

Sable Bellew enjoys drawing, writing, good food.