Chronic Pain and Fermentation

Chronic Pain and Fermentation

Ralph Davis

→BFA SC 2022

I am trans and I have chronic pain. RISD would say that I am differently abled. These factors make it difficult for doctors and specialists to tell me when I will feel better, or if I will feel better. Being trans and being in pain are often linked to one another, in ways that are flattening and often humiliating. It is familiar to feel powerless in exam rooms.

My research into fermentation began in a rigid, studious place. I wanted to see if my kombucha would react positively if it was sung to, read to, or otherwise accompanied. Thixs is because my ingrained idea of research was tied so heavily to a preposition following the word “research” itself. I knew what it was to be researched upon, researched on, researched by. I am more familiar with the role of examinee and less so with examiner.

My pain flared up when I returned to my hometown. I wasn’t sleeping well—not necessarily because of pain, but because of my preoccupation with the threat of pain. In some ways, the anticipation of pain and discomfort had become more life altering than the pain itself.

At the beginning of all of this (March), while packing our things, reconstructing our lives in different walls in different cities that didn’t love us, I was distracted by my surroundings so much that I almost didn’t notice the pain at all. Maybe it wasn’t even there. When I arrived at a place of rest, a house I half grew up in, outside of Chicago, I was confronted with a sudden lack of distraction. In some ways, it was the least distracted I have ever been. Soon, within this stimuluslessness, I had resettled, if only a nominal resettling. Every time I sat still, I became completely preoccupied with my Pain Brain. this is not right. this is not right. this is not right. It was a new pain, one that I wasn’t sure could be helped.

And this was really scary. At first, the solution to this preoccupation was to remain otherwise occupied. To make (bread) and make (jewelry) and make (paintings, meaninglessly) until I became exhausted, and then to fall into bed and close my eyes fast enough to disorient the discomfort. What was scarier was when busyness stopped working.

My mom says that the gut is the first brain, and the thing between your ears is your second. At 3 AM, on my last dose of antibiotics (which did little for my pain and less for my gut health), I ordered a scoby on eBay after minimal research—mostly just to feel the thrill of capitalism and to get that little text message from my credit card company that a charge of $7.23 had been detected from an online source.

A scoby is an acronym: a Symbiotic Culture of Bacteria and Yeast. It is a little mat of plant cells and bacteria that turns tea into kombucha, one of the best boosters of gut microbiomes. When it arrived, I felt love, which is a stupid thing to say, but that’s what happened. I felt something vague that I hadn’t since I left my family in Providence. I felt responsibility for this small disk, balancing between two walls of a plastic bag, floating in yellow liquid. I felt power too: I would decide where it would live for the rest of its life, its diet, its temperature, its food, its pain, its relationships, its fate.

Soon it was sinking to the bottom of a glass jar and I was outside that glass jar, watching it exist in a world I had created. I wanted it to grow so badly, even though I had always thought having specific expectations for a developing child is toxic.

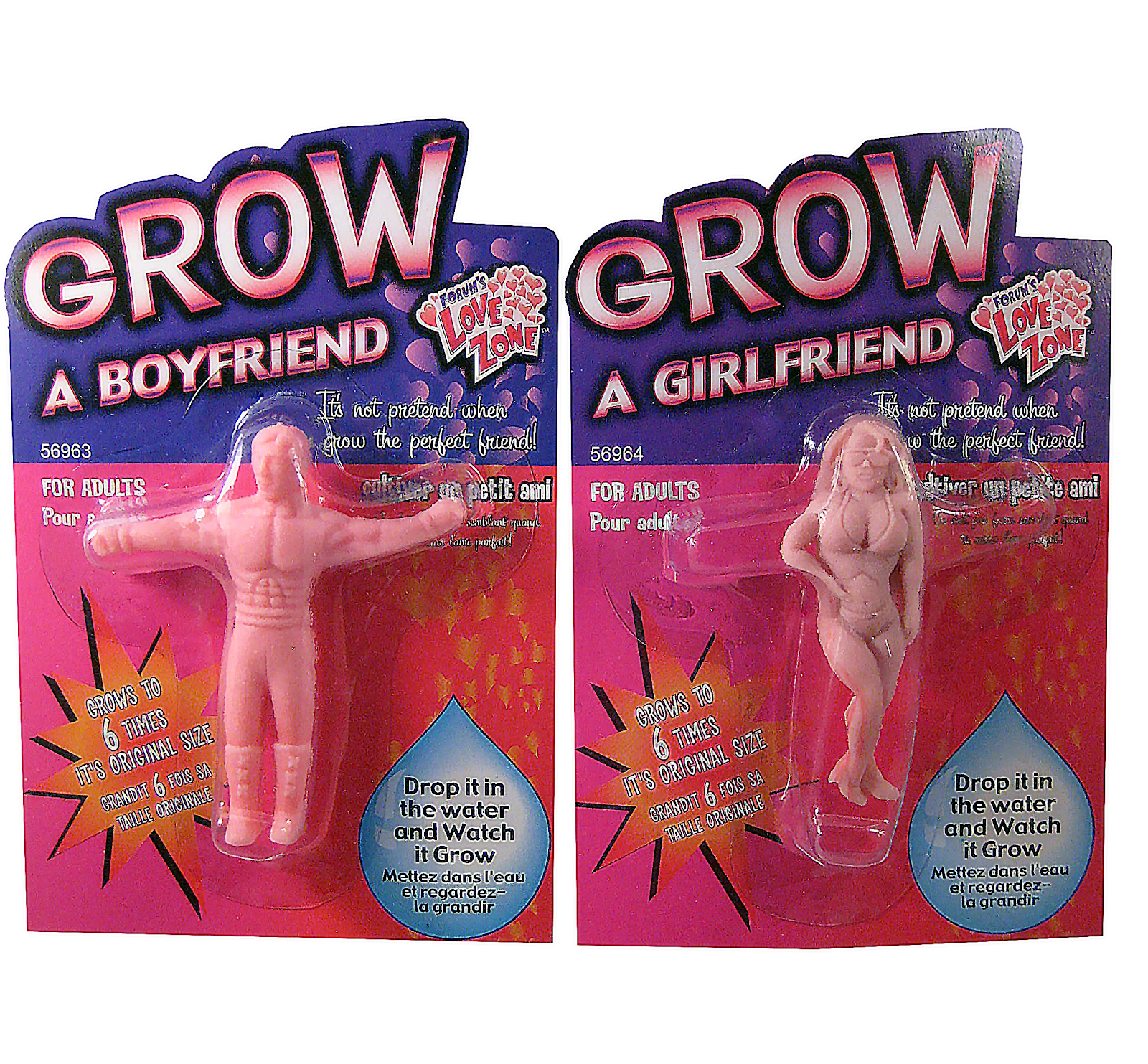

At first it was much like watching one of those small foamy men grow in a bowl of warm water. Dead, but not stagnant.

Bathbombs for instant companionship.

Then I thought about the sea monkeys I raised and killed on accident as a toddler.

Then I thought about the community I left behind in the midst of a pandemic, watching these impossibly small yeast particles form families in fast-forward. I felt all the feelings of loss, nostalgia, love, passion, and guarded hope that I cope around instead of with.

I was thinking about a lot of things, but I wasn’t thinking about pain.

Over and over again, I am reminded of the importance of cycles. Within fermentation, within transness, within love. Every time something goes away, I am convinced it will never come back again. Chronic pain is similar—some mornings it is difficult to move my legs. Some mornings I don’t think about them at all.

Some of this rigidity of thought is due to my age. I am very young, but will never be this young ever again.

If the pain continues, will I be able to walk at 25?

The answer is: maybe.

There might be days, much like today, when I can wake up to a mind given freedom from the body. I physically feel the absent weight of pain that is so often a part of me and yet so deeply unfamiliar.

There surely will surely be days of hunched resignation.

I know some people who keep track of their menstrual cycle with a calendar. Through enough use of this system, they create evidence of a cycle. Not just a hormonal one, but a way to expect the somewhat unpredictable. This has happened before, they say, and this will happen again and again and again until it doesn’t.

This I admire so deeply. And maybe I will have the courage to keep a calendar like this of my own pain. On Thursday, I felt great. This weekend, I wanted to stay in bed.

Saturdays have become brewing days. When I wake up, I hold a joy that sits in my gut and my sacrum. Something approaching the pride of motherhood I’d imagine. The anticipated act is simple. I dip a straw deep into the vessel. I remove a small amount without disturbing the tender scoby, who I have named Miriam. If the brew tastes ready, I remove the scoby from the surface of the wide mouth with a clean, gentle hand. It feels like a slice of skin, resting there: sometimes a labia, sometimes the bottom of a soft strong foot. This step I take seriously. I rehome the well-fed scoby into another jar, one with many other scobies inside, resting and growing and waiting to eat and create again. Some of them are thicker than others, three or four weeks old. They exist on a gradient of yellow brown to white, bubbling, ugly, by all accounts, and organ-like (a case cannot be made for the beauty of a scoby). Some feel like tissue paper, completely translucent in the light, only days old. I feel a sense of pride looking at this jar full of life, but I cannot claim any ownership over the little ghosts floating there. I know they would reproduce with or without me. They, at once, feel love and complacency.

I pour the sick, dense liquid into another vessel, this one with a stopper. The liquid feels sterile then, without Miriam, but of course it is not. A week ago, this was only tea, no more exquisite than the fat left sideways in a Dunkin’ Donuts cup found in any Providence gutter. The process turns dark red black tea to a golden yellow, turns sugar into tiny worlds of gas, submerged. The scoby does not care whether you’re going through a breakup, have just lost your phone, or are having a bad pain day. It is about as responsive as concrete, and more politically moderate. Every week, unflinchingly, I give care and love. It takes the loose shelter, food, some sounds of a house well lived in, maybe a song in between loads of dishes done, and becomes something completely out of my control.

Every week, I remember what it felt like last week to perform these same actions. If I wanted, I could create a schedule, log it in Google Calendar, and be certain of something for once. Last week on Saturday I felt this way inside my body; today is Saturday again and I feel different. Last Saturday I needed new meds. This Saturday I have them. Next Saturday, I will know what it feels like to have a small camera inserted inside my body in order to run some tests. But I know that I will return to this action, a ritual one, that fixes me to this spot and discourages distraction.

These are cycles, gestation. It is chemistry. It is both intensely predictable and wildly enigmatic. I can communicate with this scoby in a jar about as much as I can communicate with my own body, with all its shortcomings and aches. My body and the scoby both react more favorably to female voices than male ones. Our favorite Grateful Dead album is Pembroke Pines ’77. Neither of our bodies understand English, Spanish, or Latin.

I am not sure whether this is research I am conducting or therapy. However, because of this series of rituals I hold myself to, I can begin to empathize with examiners. I have become an examiner in the sense that I have no control over the actions or non-actions within fermentation, I can only watch. I cannot control what happens day to day within my body either, whether I will get ill or get better. This process has also discouraged me from considering these binaries.

I am at once sick and well, in pain and in bliss, accompanied and alone, a soul and a body.

Does singing to my scoby make my pain better? It is impossible to say. Like many fixed factors of this life (taxes, capitalism, internet issues), there is only so much to be done preceding exhaustion. I know that the time fermentation requires has provided me with a weekly scale that is legible only to me. I know that within my scoby, there is the memory of my clean hand holding it, and it holding me. I know that I feel accompanied walking with these microbes inside of me, like a medium-sized church.

Ralph Davis, Untitled, 2020

Ralph Davis, Untitled, 2020