No Longer Transparent:

A Conversation with the Curator

Irene Chung

→MFA IL 2024

↥ Yuxuan An (MFA SC 2023), Still need to talk about it, chainmail scrubber, scrubber yarn, beads, buttons; worn by the artist; photo by Honglin Cai

IC: Thanks for talking with me about No Longer Transparent, Yuxuan. I hope you don’t mind if I start by sharing your powerful exhibition description, which appears in the entryway at the Gelman Gallery:

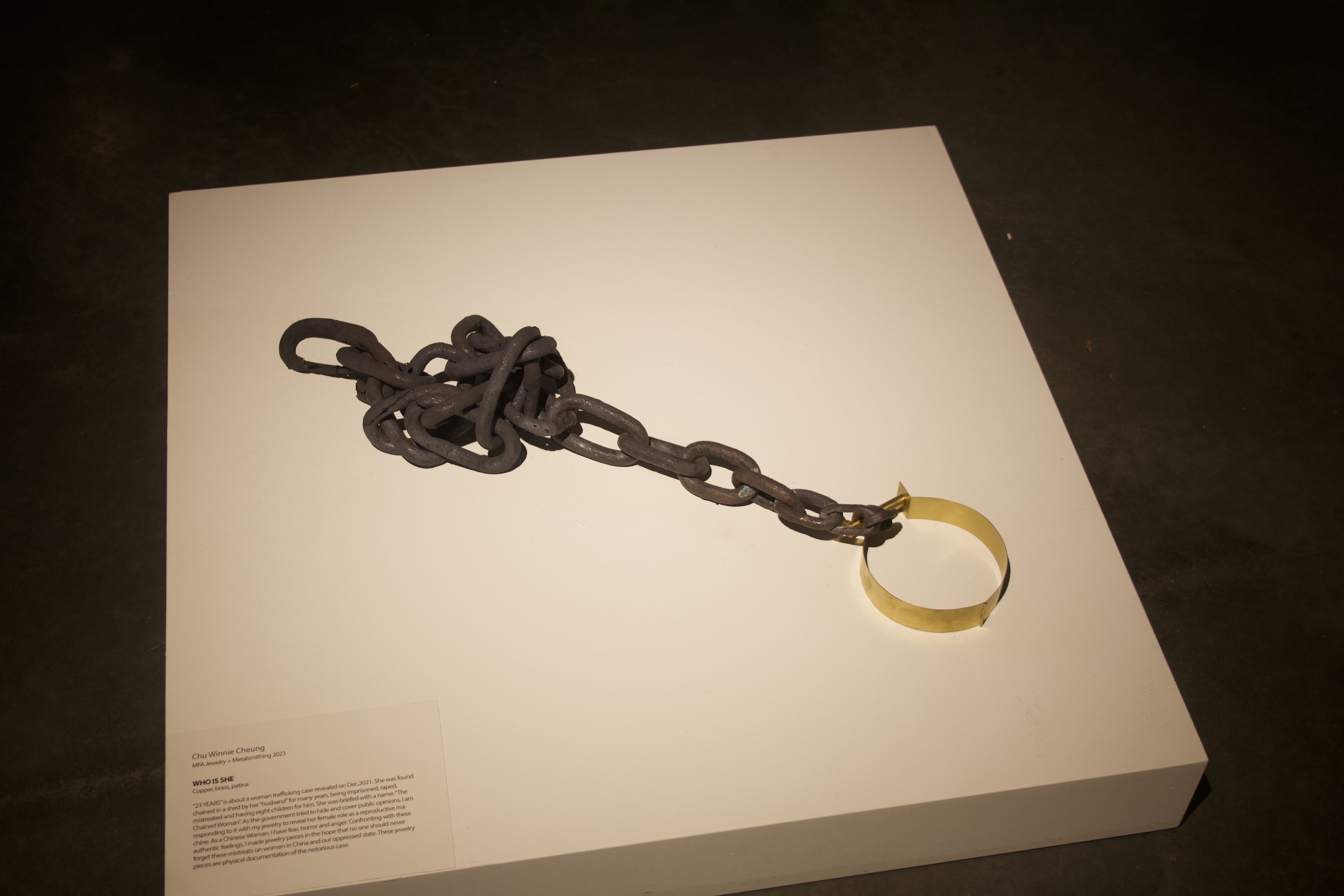

Even during modern times, Asian women still are often treated as objects. In China, the “Xuzhou Chained Women” caused a massive public outcry, but has since gradually faded out of the public consciousness without resolution or justice. In the United States, the 2021 Atlanta spa shootings took the lives of 6 women of Asian descent, adding to the fear they already felt after multiple attacks during the pandemic. Recent events like these have brought pain to Asian women, whose suffering is seen as insignificant.

As James Baldwin said in his speech on “The Artist’s Struggle for Integrity,” New York, 1962: “You must understand that your pain is trivial except insofar as you can use it to connect with other people’s pain; and insofar as you can do that with your pain, you can be released from it, and then hopefully it works the other way around, too; insofar as I can tell you what it is to suffer, perhaps I can help you to suffer less.”

Through this exhibition, we hope that we can come together to bravely tear away the suffocation, and become no longer silent and no longer transparent. Through our collective strength, we hope to confront what has been deemed acceptable and convey our aspirations for the global liberation of Asian women.

The objective of this exhibition is to give voice to Asian women and their life experiences during the pandemic. Could you tell us a little bit more about your personal goal for this exhibition and how you feel about the “Xuzhou Chained Woman” incident, especially for those who didn’t know about it?

YA: Firstly, I’ll respond to your second question. “Xuzhou Chained Woman” is a tragic event, in which a woman was found chained inside a shed in Xuzhou, China. It is also a news story that involves various structural issues and criticisms, so it’s difficult to summarize here. Instead, I’d like to talk about my thoughts on this incident. I feel hopeless like most of the public who were following the news. Despite women becoming more robust and more socially active nowadays, countless women are still living under the shadow of patriarchy in East Asia, in which females are still constantly being objectified and sexualized. Oftentimes their value is reduced to their reproductive function. This story from Xuzhou is just the tip of the iceberg—there are so many women remaining silent under oppression, and I believe more stories need to be told.

Another thing that upsets me, as well as the public, is that the authoritative power has not been scrutinized after this incident. This news came out and received the same amount of attention as the Beijing Winter Olympics at that time, but the government failed to conduct a thorough investigation. The identity of the woman remained unknown, and many activists also disappeared from the Internet. Everyone is living amid mystery and misinformation.

In the meantime, I don’t want the public to forget about her and other women who might be suffering from mistreatment and abuse.

IC: How important is collective memory in relation to this exhibition?

YA: In the post-pandemic era, the news about hate crime and incidents towards the Asian community is fading out quickly, and I believe a lot of stories and events have to be remembered.

When you find the news and the public are not on your side, you are the only person who can protect yourself. I had been living in New York for a year and a half, since the beginning of the pandemic. Whenever I was alone walking outside at night, I always walked fast and pretended to be well-defended because of my small figure. I think this is what a lot of Asian women were experiencing during the pandemic, and I think the feelings of fear and trauma need to be documented and shown to the public. In this way, we can form collective power and empathy. We need someone to initiate telling our stories, and I’d love to do this for our community. I think my main motivation is the urge to express mutual feelings among our group during the suppressed pandemic era. I believe that we all need a platform to tell our stories more publicly. I am grateful and glad that RISD gave me this opportunity.

IC: As an Asian female curator, it’s clear you felt this task

was urgent.

YA: I think there is still a stereotypical impression that Asian women are obedient, so they are usually deemed unimportant and secondary and are easily forgotten and neglected by the public. While women’s rights activism in Western society is fighting for abortion rights, equality in the workforce, and other civil rights, the women’s rights movement in Asian is focused on abuse, sexual harassment, female domestic roles, and their reproductive function. That’s how I know that we still have a long way to go.

And this is true in the US as well. I think Asian women in the Western context are living in a similar situation.

I also wanted the show to represent women in the broadest and most empowering terms. I was inspired by Johanna Hedva, who writes in “Sick Women Theory”:

Though the identity of “woman” has erased and excluded many (especially women of color and trans/nonbinary/genderfluid people), I choose to use it because it still represents the un-cared for, the secondary, the oppressed, the non-, the un-, the less-than. The problems of this term will always require critique, and I hope that Sick Woman Theory can help undo those in its way. But more than anything, I’m inspired to use the word “woman” because . . . the word itself can be empowerment.

In this exhibition, I am not representing females based only on their biological sex. I consider the word “woman” to encompass different forms of females. This is why this show includes work from Asian sexual minorities. Because East Asian culture tends to emphasize family and traditional gender roles, we are facing more hardship than others. I hope to show this expansive side of the story through this show. We have to support each other in opposition to patriarchy.

IC: In your statement, you quote from James Baldwin’s speech “The Artist’s Struggle for Integrity.” Could you elaborate on it? What do you think are the functions of artists in our society?

YA: Having creative rights is already very fortunate compared to many people. Because we have these rights, I think artists should be more accountable and take more social responsibility or pay more attention to social issues. It can not only be about observing life from a macro approach, like in sociology, but also through a fine lens, and discovering those non-mainstream, alternative topics, and diversifying our society.

In a speech in 2019 Chizuko Ueno, Japan’s most well-known feminist, told the audience,

“Your advantages come from the privileged environment you grow up in, and you should use your ability to help others. Do what you can, and admit your vulnerability and help each other out.”

If those of us who hold higher education degrees won’t voice the issues, who else will tell the story for us? Living in a world filled with insoluble problems, we need to gather together.

IC: Thank you for sharing that perspective and your deep commitment to bringing us all together. As an artist in the show, I appreciated it! Tell us, what was the curatorial process like? Are there any special moments you would like to share?

YA: I was very excited when I received so many submissions because the speedy response from the artists was beyond my expectations. What touched me the most is that a lot of participating artists shared their thoughts with me in the submission form. Although we did not know each other at that point, I could feel their trust through their words,and that was the moment when I realized the exhibition

was meaningful.

I also felt very inspired to see many artists who are much younger than me discussing very bold and powerful topics through their work. That gives me confidence, and I am very much looking forward to seeing their future work.

IC: What were some of the logistical parts of the curatorial process like for you? Walk us through it.

YA: It was interesting to gauge how to balance the whole space, which was like making a new re-creation from those works. Mark Moscone, Director of Campus Exhibitions, provided me with lots of valuable advice. I also want to thank Kevin Hughes and Gunnar Norquist for helping me set up everyone’s work. I very much appreciate them.

In terms of the ambiance of the exhibition, I think it feels sentimental, because all the artists are telling stories from their struggles and traumas. I am very proud of the participating artists’ work. I feel that we are in this together, and I did my best to display their work in the best possible way.

IC: Do you want to share your plans for your career development?

YA: I hope to continue to be involved in the art industry in different ways. As opposed to being just an individual artist, I will continue to gather collective strength with like-minded people to convey powerful messages to the public and to help those in need. I am hoping to see more urgent societal changes in the future.

IC: Thanks for your time for the interview.

YA: My pleasure.

Yuxuan An (b. Taiyuan, China) is an artist based in Providence, RI, and New York, NY.

Irene Chung (b. Taipei, Taiwan) hopes to tell stories that provoke thought and social changes.

No Longer Transparent is on view at the RISD Museum until December 11, 2022.