Girls Just Want to Be Dead and in Your Inbox: The Bastardization of Folkloric Oral Tradition for Digital Social Capital

Katherine Fu

→ BFA CER 2025

WINNER: With its humor, mystery, introspection, and universal themes, this essay beautifully embodies writing redefined. Overall, it lays out a compelling critique on a cutting-edge topic. Readers are taken in by an engaging voice that blends personal and scholarly genres, discussing historical context, personal experience, and careful analysis with casual vernacular uncommon in academic texts. All this is done in a multimodal form that does a lot of work for the piece. The incorporation of images provides real-world texture; the all-caps headings and star-shaped bullet points reinforce voice; and the color scheme of green and white text on a black page evokes nostalgic html aesthetics as well as the “dark forest” beyond the campfire. This piece seems to take up the invitation to push boundaries at every opportunity, but fine-tunes those choices to be purposeful and effective.—Meredith Barrett

In 2016, like most other 12 year olds, I desperately wanted more friends. My motivation, however, perhaps diverged a bit from typical preteen desires to gain social standing. I admit it would’ve been nice, but I didn’t need to be popular. I needed to escape Carmen Winstead.

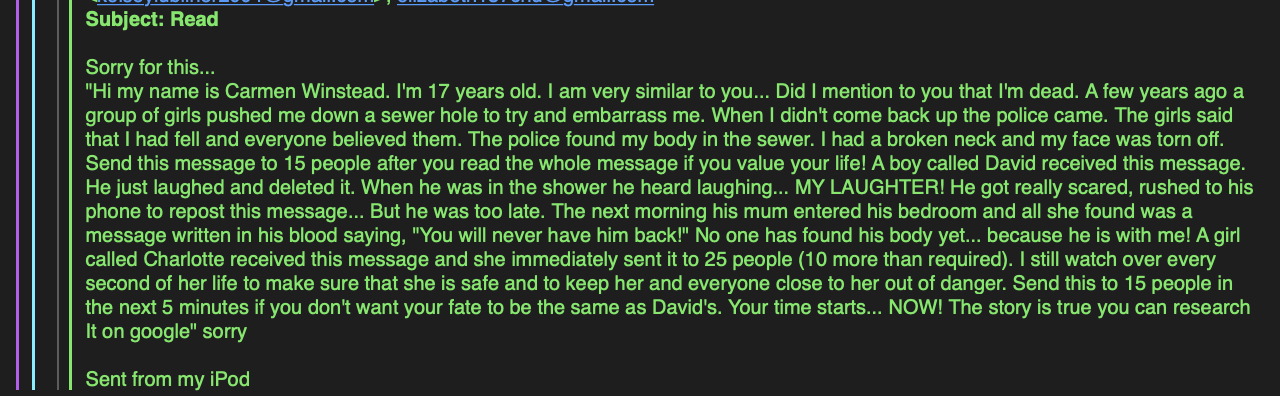

I met Carmen through an email from a friend. Her brief yet urgent plea appears above. To me, Carmen was real, and Carmen was coming. I needed those 15 friends to be free from her karmic clutch, and looking at the sad eight email addresses I could muster up, I was fucked.

THE CARMEN CASE STUDY

Aside from scaring all of the preteens in the general vicinity of my elementary school, Carmen’s story presents a fairly holistic representation of the state of contemporary digital folklore and its mechanisms. At its core, the process of creating folklore is as follows: a folk group, meaning a collective with at least one shared characteristic, shares oral content within the group. Over time, this manner of sharing becomes standardized and forms the tradition through which their subsequent folklore spreads. These same guidelines apply on the internet, albeit in different forms. Any number of exclusive in-groups could be a folk group and as James Bacon notes in his 2017 thesis tracking digital folklore, “The digital vernacular contains many of the same types of folklore found within the oral tradition.”1 The word “vernacular” here replaces the term “oral” and refers to the inaudible lingua franca of the internet; dialogue on the web occurs predominantly through visual (memes, reaction photos) and written communication (emails, tweets) as opposed to vocal.

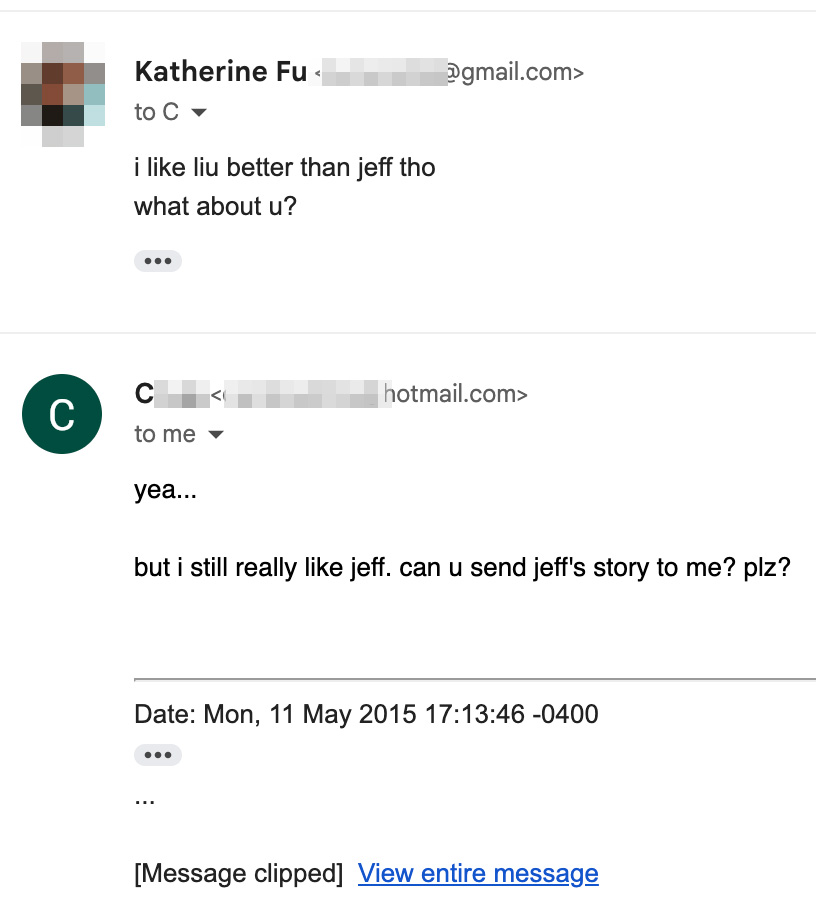

A friend and I exchanging our favorite internet horror legends

The birth child of the chain mail and the urban legend, Carmen draws on two popular forms of messaging. Chain letters predate the inception of the internet, with “luck letters” appearing in the 1900s promising good luck to distributors.2 Urban legends, while cohering generally to the classic folklore framework, have adopted more of a modern connotation to imply recency. The former provides Carmen with the ability to reach a vast audience. The latter gives her the karmic and superstitious backing to ensnare them. With the steroidal impact of the internet, the power of both chain letters and urban legends, and thus Carmen, expands astronomically. With every email received, as many as 15 new emails go out. Carmen spreads at an exponential rate. The speed at which information disseminates on the internet creates the perfect breeding ground for such digital folklores to capture the collective consciousness. These legends continue expanding to a point of murky origin, unclear termination, and no return.

WHO CARES?

The easiest and most obvious response to Carmen-like schemes is, “Who would believe that?”

I would. I did! And you would too.

Let us examine the campfire story. The classic campfire tale relies on the illusion of intimacy and a deceptive environment to impart terror. Stories typically pass down from an uncle or a grandfather or a friend-of-a-friend who swear the teller to secrecy. Having established sufficient credibility, the storyteller tells their forbidden story under the cloak of darkness and surrounded by a ring of trees. The dark forest is paramount to the potency of the campfire story. It narrows the realm of strict reality to a circumference of firelight. The shadowy world of possibility gives the teller’s story life. Of course, there is no way of confirming that say, Bigfoot, truly exists, but in the inky expanse behind your back, there is no way of knowing that he isn’t standing right there either.

In “The Internet Aesthetic, Experience, and Liminality,” Stephanie LaFace proposes that as the Internet’s experiential features “give rise to liminal and aesthetic experiences, what emerges is consideration into new manifestations of being …We switch from a driver to a user, from a citizen to a tourist, from an engineer to a client. Thus, we dis-organize ourselves in a delusion sense only to individuate into different crystallizations of the self.”3 Extrapolating from LaFaces’s conclusions, we see that not only does the digital landscape create a liminal space of probability, but the liminal identity of users engaging with digital folklore establishes an ever-changing relationship with sincerity. Carmen’s closing line tells the recipient to google her story, but on Google, any number of users could post articles with the purported truth. In a subversion of the intimate relational aspect of the traditional campfire story, digital folklore provides the opportunity for innumerable authors to generate believability without requiring them to ever extend past the role of a stranger. The internet is our dark forest. Carmen’s home. Faced with the threat of infinite truths and their infinite consequences, the safest thing to do is to believe.

TIKTOKIFICATION

It is that small inkling of doubt that keeps Carmen, and digital folklore, alive. Not only is Carmen in good company, but her fearsome crowd is inventive and ever-growing. Digital vernacular adapts to the evolving nature of the Internet, following trends to mold preexisting lore to new structures and to establish new foundations for tales to come. Though email remains a highly popular form of communication, the inception of various social media platforms such as Instagram, Snapchat, and TikTok have shifted the usage of email towards older and more formal demographics. More than a billion people globally use TikTok, with around 73% of Gen Z, now between the ages of 11 and 26, on the app regularly.4 This age range places Gen Zers in the perfect position to be susceptible to Carmen’s ghastly charms. Her hunting ground shifts to the world of short form video.

TikToks in their purest form are videos between three to ten seconds long, often accompanied by a song or a soundbite. I focus here on TikTok because of its rapid and intense entrenchment in Gen Z popular culture. Entire careers, ranging from musical artists like Lil Nas X and Doja Cat to model Alex Consani, have undoubtedly benefited from their explosive TikTok success.5 The introduction of TikTok to the field of digital folklore adds a layer of complexity to the type of interaction Carmen-like stories recieve. While a TikTok is simultaneously a form of classic visual digital vernacular, the app itself introduces not only new vocabulary (an audio, a stitch, a duet) but critically, TikTok introduces its algorithm. Enter the beast!

SOCIAL CAPITAL

Often ominously referred to as The Algorithm by its users, the TikTok algorithm recommends personalized content to every user’s page, literally called a “for you page” (FYP). Instead of an inbox full of messages from friends, acquaintances, and the one-off spam mailer, the algorithm curates a string of videos it thinks you might enjoy. When the algorithm hits its target, recommended videos can feel prophetic—see popular phrase: tiktok really said for you page. But the algorithm is also imprecise and assumptive. Users have realized that it pushes globally trending content, often linked to a sound, regardless of personal relevance. It is impossible to avoid seeing the number of views, likes, shares, and comments on a video unless hidden by the poster themselves. Failure and success are presented plainly. The algorithm gives instant reinforcement through this individual form of currency of fame alongside the potential of real money.

Once a TikTok creator reaches 10,000 followers and begins averaging 100,000 views a month, they receive the option to join the TikTok Creator Fund. The Creator Fund, according to varying sources, pays anywhere from two cents to four dollars per view. Combining the digital trend cycle with this financial incentive creates a clear formula for TikTok success that unfortunately flourishes on attention-grabbing shock-value content. Much like Carmen’s original directives in her email to “send [this email] to 15 people in the next 5 minutes [or else],” creators come full circle to the luck letter to exploit the gray area between chance and fear. Oral tradition intersects with this behemoth of an algorithm to create motive, and motive makes a greedier person of us all.

CLAIM CLAIM CLAIM

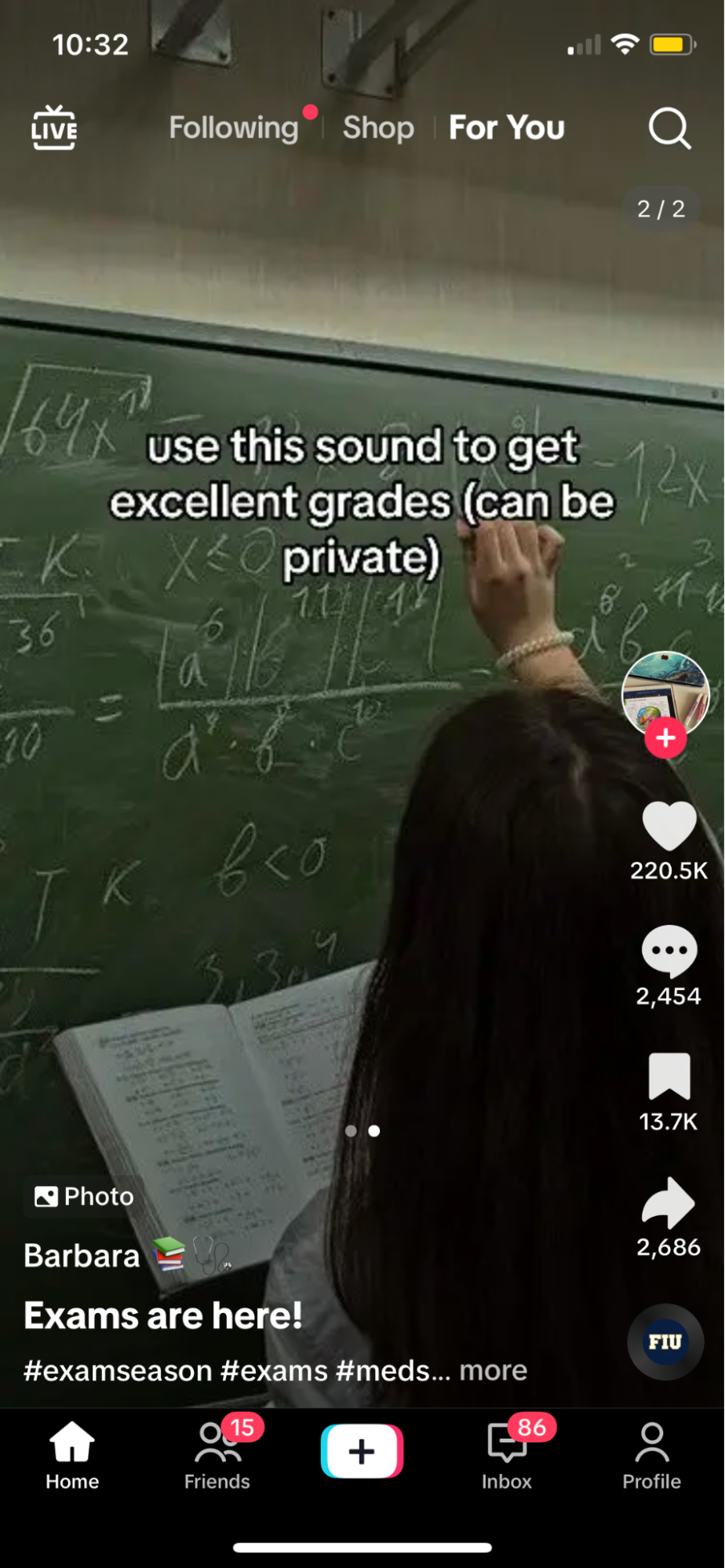

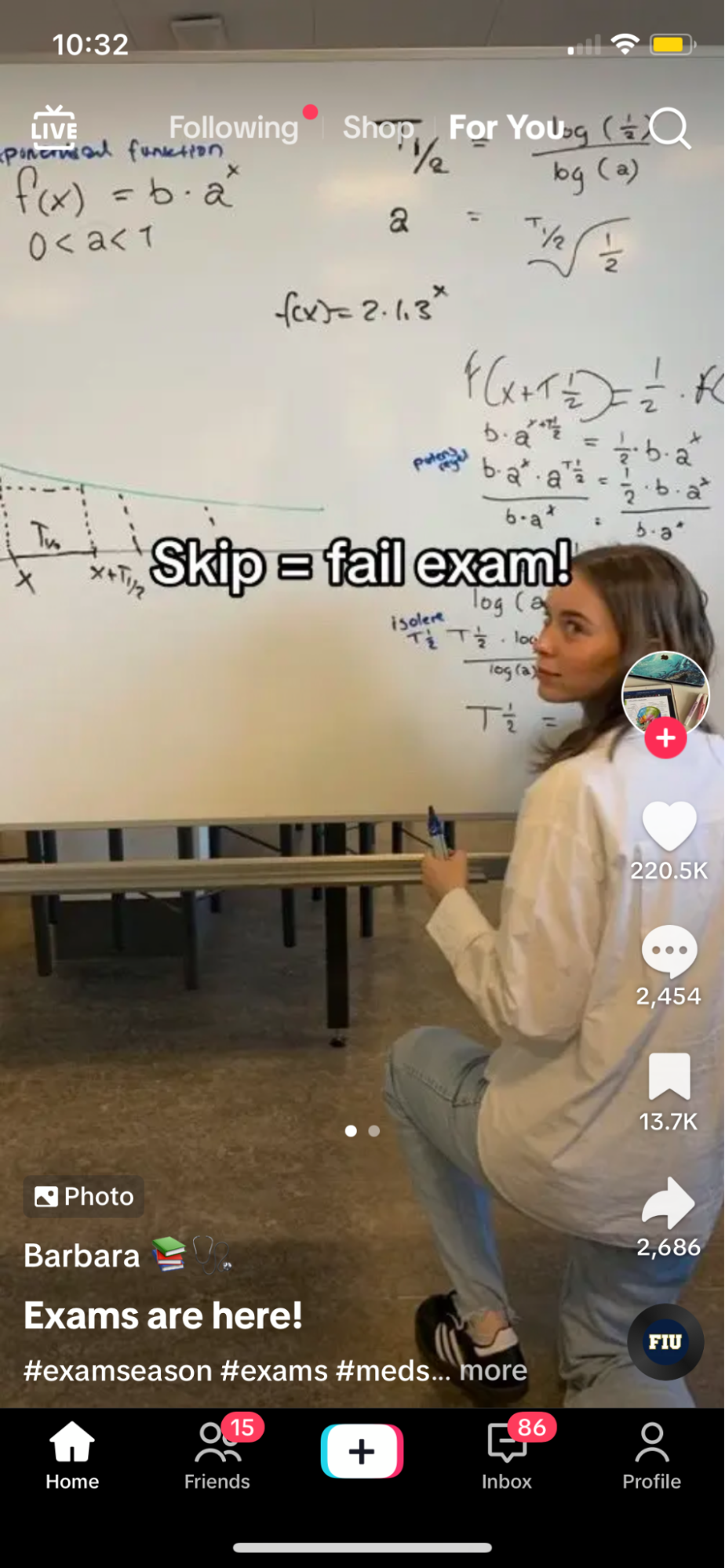

While I do my best to avoid the speculative, manifestation-fixated side of TikTok, my FYP still presented me with the above video this morning. The threat of exam season perhaps seems on the lesser end of the horrors that can befall a disobedient TikTok user, but if we reconsider the average age of a TikTok user, it can feel very real. Similar videos exist for getting good skin, getting a text back, getting skinny, getting a boyfriend. Getting skinnier. Getting a car? Then the needle swings to the complete far end of the spectrum to alarm: use this sound or your mom will die tonight. Use this sound or something terrible will happen at 11:59 PM. The set ups and cruxes of these warnings distinctly parallel Carmen’s messaging. In 1996, folklorist Alan Dundes classified the universal component of chain letters into six components: retention, compliance, compliance via mainline testimonials, copy quotas, effective distribution, and deadlines.6 His structure remains true to this day. This TikTok, as does Carmen, can be broken down to fit each component.

︎Retention, or possession: the FYP wills you to see it, therefore this message is for you.

︎ Compliance, the “or else”: what you gain or lose (i.e., the exam grade).

︎ Testimonials: evidence of the power of the video, provided by either the original lore or the sender (I swear it worked!).

︎ Quotas, or procedure of compliance: what you must do (e.g., send to 15 people, use the sound).

︎ Distribution, or circulation: sharing the video as is, as it says to.

︎ Deadlines, or expiration dates: the timeline for sharing. Evidently, if you scroll, the video disappears alongside your opportunity.

Although Carmen asks the recipient to directly forward her message, here even the simplest interaction with the TikTok propels it towards new victims. This vague notion of “interactions” refers to a sustained exchange with the video. Watching it for its entirety, liking the video, leaving a comment, saving it, or sending it to a friend all constitute actions that up a video’s interactions. Frequent interactions hint to the algorithm what trending videos are. Even accessing TikTok’s “not interested” option, which may seem like the obvious escape route, counts as an interaction, routing similar videos back to your FYP. TikTok users don’t need to actively work to send an email. Intentionally or not, the mere usage of the app, never mind “[using] this sound to get excellent grades,” spurs the algorithmic machine onwards.

CARMEN’S REBIRTH

From the late summer of 2022, an influx of videos appeared on FYPs telling of a certain 17-year-old and her gruesome fate. I immediately recognized her for who she was—Carmen had returned.

To a vast majority of users, however, rather than a reunion, these videos introduced them to the world of the chain letter. Carmen’s world.

One such Carmen TikTok

One such Carmen TikTok

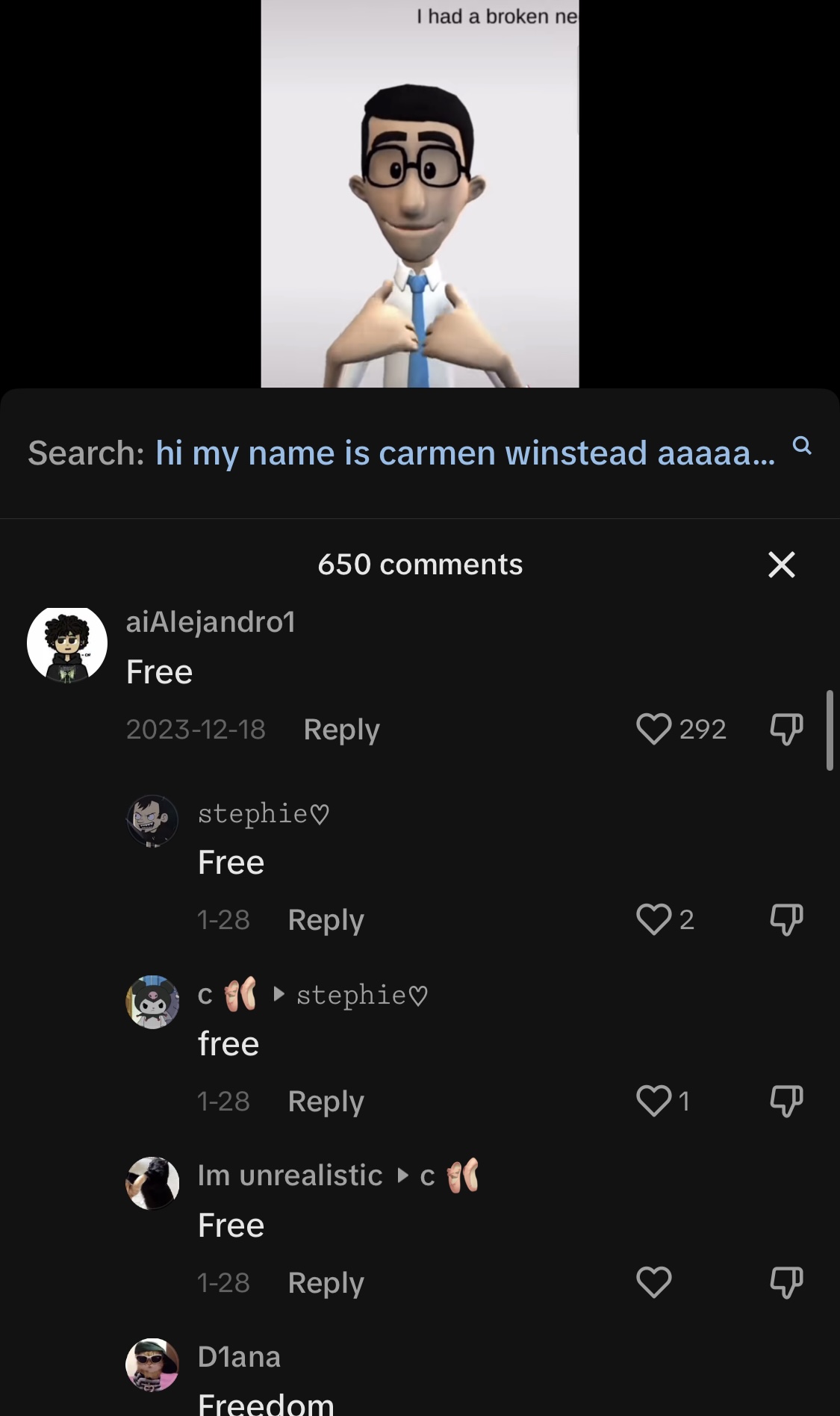

In the face of a new enemy, TikTok users began to use the structure of the app to break loose from Carmen’s grasp. Thus birthed a new form of interaction with digital vernacular, hosted by strangers in the comments section. In a twist of the compliance category of Dundes’s components, a new option was instead to “claim” the intent or energy of the video without formally adhering to its instructions. Inversely, its opposite was to comment “free,” indicating that you had a free pass from the power of the video. At times “free” can serve both attracting and repelling purposes, but users will never use “claim” on a negative video.

Although it may feel soothing to like the “free” comment, functionally the action results in the same way that liking the video would. The plethora of people commenting on chain letter TikToks creates a microcosm of the algorithm within the algorithm. Sure, some may intend to be altruistic, but these comments are an easy and sure-fire way to gain mass amounts of likes on a comment. These likes then translate not only to brief popularity, but also as inter-user exchange, which the algorithm again interprets as a sign that a video is doing well. The algorithm does not care about positive or negative interaction. It cares about bulk. In the creation of this form of reaction, more chances for opportunistic users to chase notoriety. Now, not only can users post a baiting video to gain views and such, other users can ride the coattails of its current to get their own clout. The oral storytelling tradition acknowledges its use of gimmick and its scheming nature to pass along tales. As the digital vernacular on the Internet grows, however, this tradition transmutes poorly under the umbrella of the algorithm. Always steps ahead of the average user and an unpredictable tool for others, the algorithm establishes an entirely different goal far removed from the purpose of scary stories in the dark. Oral folklore perseveres because aside from the fright, there is fun. But all of a sudden you can’t catch a break on an app you downloaded to relax on, drowning in videos and videos of manifestations and claims and dire warnings. And then it really, really is not fun.

CAN THERE BE RELIEF?

My working title for this essay was I’m Still Falling Victim to the Same Things That I Used To. While Carmen’s resurgence did catch me off guard as a specter of my childhood, I moreso found myself completely bombarded and at the whims of these “use this audio or …” videos. My psychiatrist told me I have obsessive tendencies, and I certainly was realizing this was true. I found myself making videos with these audios multiple times an hour to the point that I became exhausted from the mental burden of knowing disobedience could cause a terrible disaster. It felt incredibly unfair that the creators of these videos may have exploited compulsive inclinations I could not control for socioeconomic gain. Again, the easy question to ask is, “Why not just leave?” But it’s hard to run away from the vague sense that karma’s watchful eye is constantly turned on you. The folkloric origin of these videos becomes incredibly important in explaining the type of psychic hold they can have. The realm of fate transcends linear rationalities. In comparison to letting Lady Luck decide whether my dog makes it through the night, a quick tap and a couple of seconds seems insignificant in comparison.

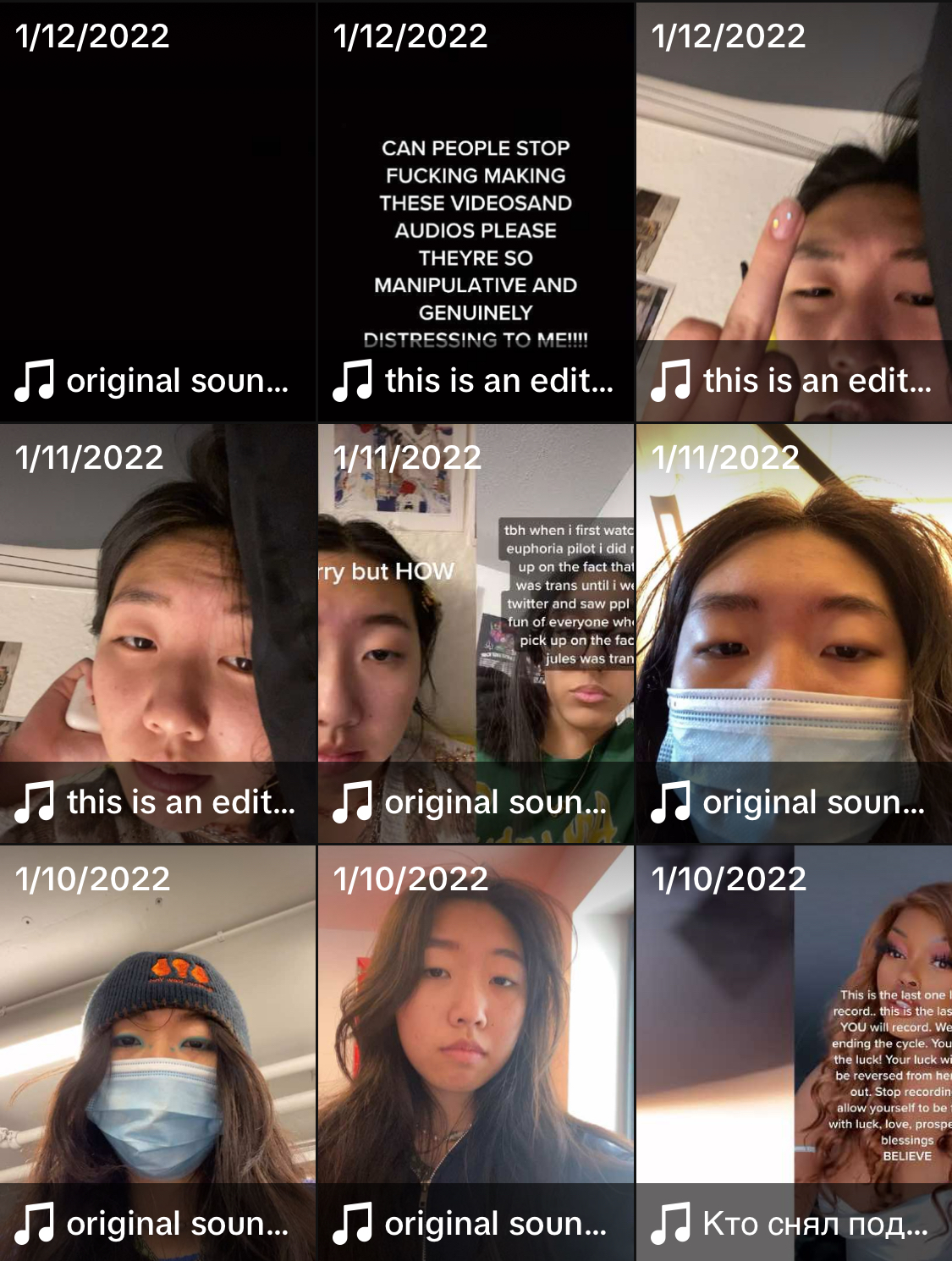

Drafts I made in compliance with chain letter videos, with one clearly frustrated vent on the top middle

Drafts I made in compliance with chain letter videos, with one clearly frustrated vent on the top middleThe only real way for the videos to go away is to speak to the algorithm in its language, which is to say that you are not interested. Genuinely. Instead of finding the button, you have to scroll as if it were the news. An understanding of why these videos end up on your FYP can also help break the mental lock. The algorithm is not a karmic god. It doesn’t know it’s hurting you. And so the hard part is to not let it.

In the years since I first met Carmen, I have seen her in many iterations, some made to scare, others meant to jest. Even though she definitely does fall into this category of chain mail, it’s easy to find the holes in her story. It’s easy for me to ridicule the self that believed her and easier to let her go. There is a hint of that same joy that screaming Bloody Mary in a school bathroom did in Carmen’s tale. TikTok videos don’t have that. Their generic threats, once reckoned with, ring hollow. Collectively, we should not be giving them the time of day. Easier said than done, I know, but there are better things to be doing. Like watching an actual horror movie. Revisiting your emails from middle school. Finding joy in fear again.

NOTES

- Jasen Bacon, “The Digital Folklore Project: Tracking the Oral Tradition on the World Wide Web,” (2011), Electronic Theses and Dissertations, Paper 1398, (2011), https://dc.etsu.edu/etd/1398.

- Daniel W. VanArsdale, “Chain Letter Evolution,” Carry it On, carryiton.net/chain-letter/evolution.html#s3-8eff ective_distribution (accessed February 7, 2024).

- Stephanie La Face, “The Internet, Aesthetic Experience, and Liminality,” CMC Senior Theses, 1675 (2017), http://scholarship.claremont.edu/cmc_theses/1675.

- Lindsay Kolowich Cox, “The History of Social Media since 2003,” HubSpot Blog, blog.hubspot.com/marketing/social-media-history (accessed October 11, 2023).

- Jessica Martel, “16 Ways to Make Money on TikTok in 2024,” Time, https://time.com/personal-finance/article/ways-to-make-money-on-tiktok/ (accessed January 11, 2024).

- VanArsdale, “Chain Letter Evolution.”

Katherine Fu has a year until the rest of his life.