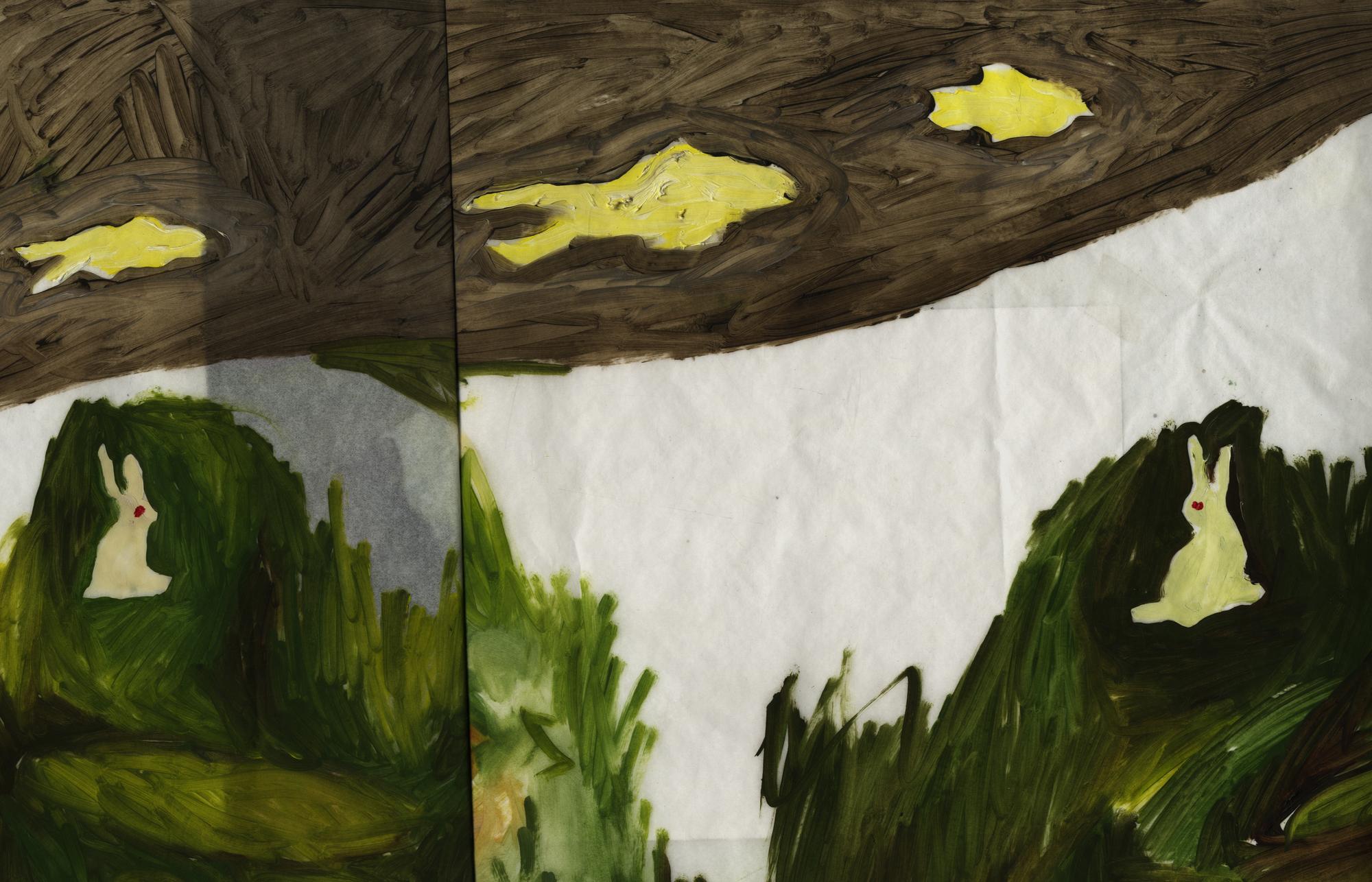

Tales of Fish in the Sky

Brady Mathisen

→BFA SC 2023

1

2

He sits on a bench that faces a park. The park is clear and empty, just a rectangular patch of grass with two trees, one on either side. There are no interruptions in the skyline, just the soft gray of the morning’s cloudy cover. He sits with his knees together, his two dusty shoes: two trees stuck into the ground in their stillness. He wears brown pants, and the creased line down the middle of each leg is much softer than it first looked at the moment of pressing. Wrapped around him is a sweater of softly knit greens and blues, and on his face sits a pair of round glasses that magnify the lines around his eyes. His silver hair verges on shaggy but it is not unkempt. On the bench, he waits three hours, still and silent aside from his breathing and his shaking limbs.

The aquarium across the street opens and he stands, walking over to the entrance. There are no words exchanged between the door attendant and the man as he enters the building. It is a relatively small aquarium and there is only one tank; however, the tank is massive and fills the majority of the warehouse-sized room. It casts the remaining space in a deep blue with soft lines projected onto the concrete floor which mimic the motion of the tank’s contents. The only sound in the room is the shuffle of the man’s feet on the floor, shifting to find his position to stare at the tank, transfixed by its inhabitants.

They’re all orange and no larger than the size of a child’s palm, but there are hundreds of them that fill the tall tank, sparkling and oscillating in waves of motion. He inspects a few near the front: a small one has sprinkles of yellow on its tail; another has bulging eyes full of introspection. The old man adjusts his gaze to the whole group and sees how they interact. Sometimes they form grouped lines in the tank and then patterns, weaving themselves through the water’s own motion. Sometimes they are still, frozen, with inquisitive glances at the man. He wonders what they think of him, what they say to each other. They are all goldfish and they are spectacular.

The man had stayed there for hours when the lights turned off, letting him know the aquarium was closed. He had been the only visitor the whole day. He loves those fish with everything in him. He steps back outside to a street darkened by the sun’s departure and walks back to the park and reclaims his bench seat from earlier that day, planning to sit for just a moment. It takes him a minute to sit with his creaky knees but eventually a cane rests across his lap. As the man tips his head up to the sky, he sees a peculiar sight: the stars, which do not ordinarily shine bright here, are glorious. They are shaped like the fish, swimming free in the night’s waves.

3

And so I ask the water, “What is sky?

The sky is always above us, one does not look down at the sky—Is the sky relative?”

The water responds and I continue, “If the sky is what is above, does that expand past a colloquial sense of the term sky, the atmosphere’s air? And for the beings that exist under, what is their sky?”

In my own thoughts I think, so the moles underground have a sky of dirt, and the crabs underwater have a sky of sea, perhaps.

“I have seen your perfect reflections of sky on your surface. Water, what is your relationship to sky? As you evaporate, do you become sky?”

“Then can we all claim to have a sky full of sea?”

The answers I am given are not transcribable into the written form, but the sounds of lapping waves are the most profound answers I’ve found in search of understanding the sky.

4

The fish of the seas were content, as were the fish of the rivers, as were the fish of the ponds. Some of the fish of the sea, a group of seabass, loved the strong current. On days that the sky was gray and the sea was a dark blue, they would swim as hard as they could against the forceful waves and propel themselves great distances and before returning: a game. The five of them were silver and glittered like small stars in the dark waves when the light hit them. Their fins were dark, almost black. The fins were invisible when the sun was down, just a whisper of movement seen only when the water was calm. One of their favorite activities was to jump out of the water in small parabolic arcs.

One day as they leapt, something remarkable happened to one of the sea bass. He did not feel himself begin the descent back into the waves of a familiar home, but rather continued to feel the fresh wind. His fins were flapping fast, and they kept him above sea level like little wings.

Right above the surface he flew, his back-tail and small fins keeping him soaring. The other bass saw this action and attempted it for themselves, but they did not succeed. As always, they dove in the air before starting the inevitable descent back into the deep blue.

This flying bass was delighted by the experience. From above, a group of seagulls noticed the commotion, for they had never seen such a strange looking bird. What was it doing, so shiny silver, soaring close above the waves and not diving for food? One seagull flew down and asked the fish how he learned to fly. The fish responded that he was not sure. They conversed further, the seagull describing the clouds and the feeling of rain; the bird describing starfish and the ocean’s floor. Just as the fish enjoyed being out of the water, the seagull found joy in being so close to the textured surface, and so they flew there for a while, a bird below sky and a fish above sea.

5

The fish begins to engorge itself on my insides: first my stomach, then my intestines, then my kidneys and liver. Soon all that remains inside my skin’s encasing is water; it consumes my bones and uses my skull for shelter and resting. The fish, massive and filled with my blood, finds itself at home in my skin full of water. What a joy to be full of fish.

Brady Mathisen is a critically acclaimed “artist,” “writer,” and “fish lover.”