How Is a RISD Broken Ankle Different?

Juri Kang (BFA TX 2025), Alex Hoffman (BFA SC 2022),

and Asher White (BFA SC 2022)

In “The Ethics of Care, Dependence, and Disability,” Eva Feder Kittay designates anyone living without a physical disability as “temporarily abled.” It’s a subtle inversion of everyday language, and its implications are profound. “Human beings are naturally subject to periods of dependency,” she reminds us. “If we conceive of all persons as moving in and out of relationships of dependence through different life-stages and conditions of health … then the fact that the disabled person requires the assistance of a caregiver is not the exception, the special case.” In daring us to confront that our self-sufficiency will, at various moments, break down, Kittay urges us to question our valorization of independence and autonomy, to embrace inevitable facts of life, to develop our comfort with interdependence and collaboration. She is ultimately calling for a massive shift in the way we view disability.

I was reminded of this text as I sat down with Juri and Alex, both of whom, over the past six months, have learned firsthand that our independent mobility is not guaranteed. Juri and Alex each broke an ankle in late August and spent the better half of the fall semester recovering. They navigated around campus using, variously: crutches, a few wheelchairs, a “peg leg” (a knee sling called the iWalk), a scooter, a cane, a cast, and a boot. Juri is a first-year student I reached out to and Alex is a senior whose ankle I watched break before my very eyes during a vacation in Maine. These two students, each on their ways in and out of RISD, met for the first time after hours in a College Building classroom and opened up about their experiences. — AW

I was reminded of this text as I sat down with Juri and Alex, both of whom, over the past six months, have learned firsthand that our independent mobility is not guaranteed. Juri and Alex each broke an ankle in late August and spent the better half of the fall semester recovering. They navigated around campus using, variously: crutches, a few wheelchairs, a “peg leg” (a knee sling called the iWalk), a scooter, a cane, a cast, and a boot. Juri is a first-year student I reached out to and Alex is a senior whose ankle I watched break before my very eyes during a vacation in Maine. These two students, each on their ways in and out of RISD, met for the first time after hours in a College Building classroom and opened up about their experiences. — AW

AW: Hi, you two. So, what happened?

JK: I broke my ankle exactly one week before school started and then I came to college, as a freshman, with a broken ankle. [laughs]

AH: That’s crazy.

JK: Great start to my college experience.

AW: And Alex?

AH: Same. Well, I’m a senior. But yeah, I broke my ankle—my tibia and my fibula—at the end of August.

AW: Exactly one week before school started.

AH: Exactly one week before school started. Wait a minute … [laughing]

AW: Do you think it happened at the same moment, miles apart?

JK: Uh, mine was … August 26th.

AH: August 24th. Beat you!

AW: [To Alex] You’re the trailblazer. You walked so she could run! [laughter] Sorry. Okay, so as people who, prior to having broken your ankles, lived without physical disability, what did you know of RISD’s relationship to accessibility?

JK: It was the peak of COVID when I was in high school, so I couldn’t visit RISD. I didn’t realize how big of a problem the hill would be. As a freshman, you have sometimes two classes a day all around campus. I had a lot of trouble going up and down the hill, waiting for Public Safety to pick me up. I was in a wheelchair at first.

AH: Was it the kind you could move on your own?

JK: Yeah, but if I let go it would just roll down the hill and crush everyone. But I never realized any of this—I didn’t know the campus.

AW: Most people here know that RISD is notoriously inaccessible. It’s a refrain people will occasionally level at the school, maybe abstractly, but I haven’t heard a lot of direct experiences. It just seems to be a tacit understanding …

AH: When I was a freshman, I did POSE, the pre-orientation program, and I was talking with the disability accommodations person at the time. She was talking about learning disabilities, and I was like, “So what do you do to accommodate for people with physical disabilities?” And she said something like, “They don’t really come here. They just know what they’d be getting into.”

AW: Like, “They know better than to even apply”?

AH: Yeah. She was acknowledging that the obvious limitations are just a part of the school. I can’t imagine not knowing this place and coming here with a broken leg.

AW: When was the first moment you realized that this would be challenging? Like, what made you go, “Oh, fuck … ”?

JK: I had two studios for six weeks, each seven hours a day, and those buildings didn’t have the handicapped door-opening button. So I would have to sturdy my wheelchair so I don’t roll back, and then try to open the door to get in, and then there’s a little bump at the bottom …

AW: Like the threshold?

JK: Yeah, so I’d have to try to get over that while holding the door. At What Cheer there’s two bumps and an incline ramp. I also had a cast on, so when I’d shower I’d have to put a plastic bag on my cast. I had never broken a bone before! I didn’t know how to deal with casts and stuff, and my parents are sixteen hours away. I had studio homework so I was up till 3 AM, putting a trash bag on while my roommate’s trying to sleep.

AW: I guess usually you’d have friends or parents you could rely on, but as a freshman entering college and an entirely new group of people … how did you figure it out?

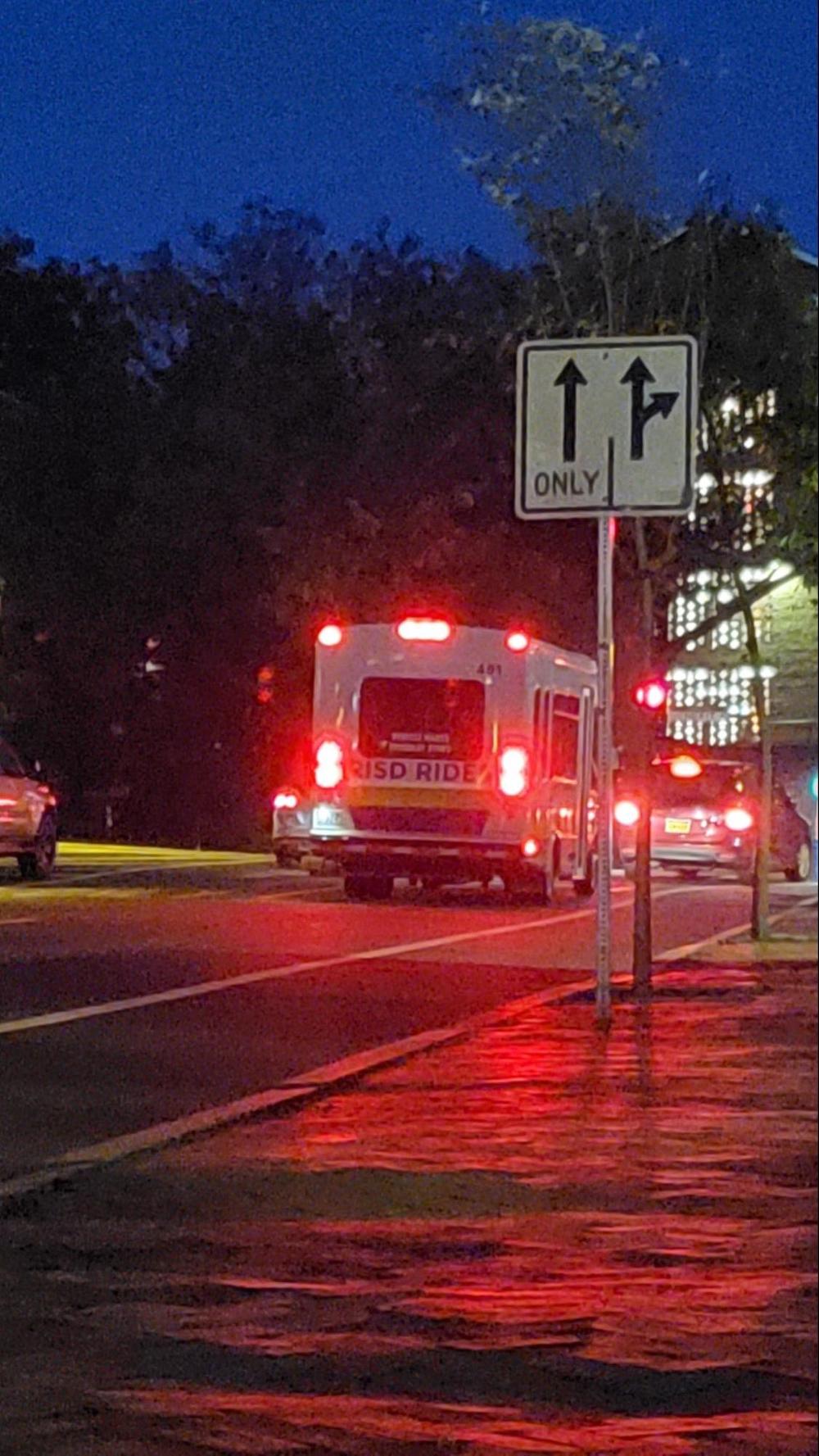

JK: I don’t know how I coped. At first it was really hard to ask for help, and sometimes I sat there for ten minutes until someone I knew would come by. After a couple of weeks, I would just call Public Safety to open doors for me. And they helped me after that, so I really do appreciate Public Safety and RISD Rides.

AW: Were they responsive for the most part?

JK: Yes and no. I understand I’m not their top priority, but sometimes I had to wait on the side of the street for an hour and thirty minutes. I was like, hmm … I would see my classmates go up the hill and to their dorm to eat dinner, and wouldn’t be able to get to my dorm. It was a two-minute walk, but because there was a hill, I had to wait for them to pick me up.

JK: I broke my ankle exactly one week before school started and then I came to college, as a freshman, with a broken ankle. [laughs]

AH: That’s crazy.

JK: Great start to my college experience.

AW: And Alex?

AH: Same. Well, I’m a senior. But yeah, I broke my ankle—my tibia and my fibula—at the end of August.

AW: Exactly one week before school started.

AH: Exactly one week before school started. Wait a minute … [laughing]

AW: Do you think it happened at the same moment, miles apart?

JK: Uh, mine was … August 26th.

AH: August 24th. Beat you!

AW: [To Alex] You’re the trailblazer. You walked so she could run! [laughter] Sorry. Okay, so as people who, prior to having broken your ankles, lived without physical disability, what did you know of RISD’s relationship to accessibility?

JK: It was the peak of COVID when I was in high school, so I couldn’t visit RISD. I didn’t realize how big of a problem the hill would be. As a freshman, you have sometimes two classes a day all around campus. I had a lot of trouble going up and down the hill, waiting for Public Safety to pick me up. I was in a wheelchair at first.

AH: Was it the kind you could move on your own?

JK: Yeah, but if I let go it would just roll down the hill and crush everyone. But I never realized any of this—I didn’t know the campus.

AW: Most people here know that RISD is notoriously inaccessible. It’s a refrain people will occasionally level at the school, maybe abstractly, but I haven’t heard a lot of direct experiences. It just seems to be a tacit understanding …

AH: When I was a freshman, I did POSE, the pre-orientation program, and I was talking with the disability accommodations person at the time. She was talking about learning disabilities, and I was like, “So what do you do to accommodate for people with physical disabilities?” And she said something like, “They don’t really come here. They just know what they’d be getting into.”

AW: Like, “They know better than to even apply”?

AH: Yeah. She was acknowledging that the obvious limitations are just a part of the school. I can’t imagine not knowing this place and coming here with a broken leg.

AW: When was the first moment you realized that this would be challenging? Like, what made you go, “Oh, fuck … ”?

JK: I had two studios for six weeks, each seven hours a day, and those buildings didn’t have the handicapped door-opening button. So I would have to sturdy my wheelchair so I don’t roll back, and then try to open the door to get in, and then there’s a little bump at the bottom …

AW: Like the threshold?

JK: Yeah, so I’d have to try to get over that while holding the door. At What Cheer there’s two bumps and an incline ramp. I also had a cast on, so when I’d shower I’d have to put a plastic bag on my cast. I had never broken a bone before! I didn’t know how to deal with casts and stuff, and my parents are sixteen hours away. I had studio homework so I was up till 3 AM, putting a trash bag on while my roommate’s trying to sleep.

AW: I guess usually you’d have friends or parents you could rely on, but as a freshman entering college and an entirely new group of people … how did you figure it out?

JK: I don’t know how I coped. At first it was really hard to ask for help, and sometimes I sat there for ten minutes until someone I knew would come by. After a couple of weeks, I would just call Public Safety to open doors for me. And they helped me after that, so I really do appreciate Public Safety and RISD Rides.

AW: Were they responsive for the most part?

JK: Yes and no. I understand I’m not their top priority, but sometimes I had to wait on the side of the street for an hour and thirty minutes. I was like, hmm … I would see my classmates go up the hill and to their dorm to eat dinner, and wouldn’t be able to get to my dorm. It was a two-minute walk, but because there was a hill, I had to wait for them to pick me up.

October 12, 2021

After the first half of Drawing studio, I attended THAD lectures, which I normally watched on Zoom from the empty Nature Lab so as to avoid a time crunch. On this day there were two classes in the Nature Lab. With nowhere else to go, I called Public Safety. Waiting outside for them to pick me up, I got stuck behind a truck filled with easels. I couldn’t get out to the street or go back into the building because both paths were blocked. I guess it was just bad timing and bad luck. —JK

After the first half of Drawing studio, I attended THAD lectures, which I normally watched on Zoom from the empty Nature Lab so as to avoid a time crunch. On this day there were two classes in the Nature Lab. With nowhere else to go, I called Public Safety. Waiting outside for them to pick me up, I got stuck behind a truck filled with easels. I couldn’t get out to the street or go back into the building because both paths were blocked. I guess it was just bad timing and bad luck. —JK

All photos by Juri Kang.

All photos by Juri Kang.

AW: What did you sense from your peers in terms of asking for help?

JK: Asking people for help is a good thing, and you should do it. But for some reason for me, it made me feel like I was incompetent. So I struggled with that. And also, it’s everyone else’s first time at college too, and they’re busy, and they don’t know where things are either. So even when I asked for help the other kids didn’t really know what to do either. It was … the word would be frustrating.

AW: Did you get the sense that Public Safety had dealt with this type of thing before? Did there seem to be a protocol?

JK: No.

AW: Woah.

JK: Yeah. At first, I remember them getting really mad at me because the wheelchair wouldn’t fit in the trunk of the Public Safety car.

AH: They got mad at you?

JK: Asking people for help is a good thing, and you should do it. But for some reason for me, it made me feel like I was incompetent. So I struggled with that. And also, it’s everyone else’s first time at college too, and they’re busy, and they don’t know where things are either. So even when I asked for help the other kids didn’t really know what to do either. It was … the word would be frustrating.

AW: Did you get the sense that Public Safety had dealt with this type of thing before? Did there seem to be a protocol?

JK: No.

AW: Woah.

JK: Yeah. At first, I remember them getting really mad at me because the wheelchair wouldn’t fit in the trunk of the Public Safety car.

AH: They got mad at you?

September 13, 2021

In the second week of school, I took this picture to remember how the wheelchair’s wheels had been hooked around the bus to prevent me from falling over. Sometimes I had to attach the hooks myself because the RISD Rides drivers did not know how. Some drivers hadn’t driven a wheelchair user in more than two years. I’m extremely grateful that one made everyone receive training on how to secure the wheelchair for future students’ safety. —JK

In the second week of school, I took this picture to remember how the wheelchair’s wheels had been hooked around the bus to prevent me from falling over. Sometimes I had to attach the hooks myself because the RISD Rides drivers did not know how. Some drivers hadn’t driven a wheelchair user in more than two years. I’m extremely grateful that one made everyone receive training on how to secure the wheelchair for future students’ safety. —JK

JK: Yeah, they were like, “Could you just go on crutches?” I fell on my crutches twice so I was like, “I’m only using my wheelchair.”

AH: It’s also exhausting to be on crutches!

JK: Your armpits hurt so much! So RISD Rides told me I could go back and forth with Public Safety. Okay, so it’s my first studio and it ends at 6:00, and Public Safety tells me, “It’s past 6:00. Call RISD Rides, not us.” I call RISD Rides, and there’s an hour wait. Eventually they come, and I get in. And there’s the wheelchair safety stuff in the back, but most of the staff didn’t know how to use it. This one really nice guy knew how to strap me in. But most of the other RISD Rides people didn’t know how to do it. They told me they all got trained in how to do it again, on how to use the equipment. They hadn’t had someone in a wheelchair for over two years. They were like, “Yeah, we all had to relearn it because of you.”

AW: Alex, did you find yourself relying on Public Safety? Were you using the school’s resources or were you just staying off campus?

AH: Aside from communicating with my teachers about specific things that I would need and communicating a little with the disability accessibility person, I was doing it myself. But I was equipped to—I have a car. And I had gotten surgeries too, so I stayed at home for a month and my mom and my sister took care of me. I had time to adjust.

JK: I’m really jealous. They didn’t give me that option. They said I had to either be fully online for a semester and couldn’t come until the spring, or I could come here and just talk with the disability services people. I felt like if I were online for three months, I’d get so depressed, thinking “I’m stuck at home because of this ankle which will be perfectly fine after two months.” Online school was for international students who had had problems with their visas, so for me it would have gone from 7 AM till noon, then 7 PM until midnight. So I’d never have more than six hours of sleep. It was clear it wouldn’t be possible.

AH: It’s also exhausting to be on crutches!

JK: Your armpits hurt so much! So RISD Rides told me I could go back and forth with Public Safety. Okay, so it’s my first studio and it ends at 6:00, and Public Safety tells me, “It’s past 6:00. Call RISD Rides, not us.” I call RISD Rides, and there’s an hour wait. Eventually they come, and I get in. And there’s the wheelchair safety stuff in the back, but most of the staff didn’t know how to use it. This one really nice guy knew how to strap me in. But most of the other RISD Rides people didn’t know how to do it. They told me they all got trained in how to do it again, on how to use the equipment. They hadn’t had someone in a wheelchair for over two years. They were like, “Yeah, we all had to relearn it because of you.”

AW: Alex, did you find yourself relying on Public Safety? Were you using the school’s resources or were you just staying off campus?

AH: Aside from communicating with my teachers about specific things that I would need and communicating a little with the disability accessibility person, I was doing it myself. But I was equipped to—I have a car. And I had gotten surgeries too, so I stayed at home for a month and my mom and my sister took care of me. I had time to adjust.

JK: I’m really jealous. They didn’t give me that option. They said I had to either be fully online for a semester and couldn’t come until the spring, or I could come here and just talk with the disability services people. I felt like if I were online for three months, I’d get so depressed, thinking “I’m stuck at home because of this ankle which will be perfectly fine after two months.” Online school was for international students who had had problems with their visas, so for me it would have gone from 7 AM till noon, then 7 PM until midnight. So I’d never have more than six hours of sleep. It was clear it wouldn’t be possible.

October 12, 2021

After an eight-hour drawing studio, I found myself less than five minutes by foot from my dorm, but I couldn’t go up the hill on my own. RISD Rides told me I’d have to wait thirty minutes. I waited inside for thirty minutes and then decided to wait outside so I could hop in and get dinner as quickly as possible. As I stood outside, the skies changed color numerous times, and before I knew it, it was dark. I sat out there for over an hour and a half before taking the two-minute bus ride to my dorm. —JK

AW: Did you feel like people were able to talk about disability within your peer group? Was there a vocabulary for it among your classmates? Was it discussed?

JK: Well, I discussed it because I complained a lot. [laughs] I talked about it with my studio peers. I’m very thankful to them. The first week of school, we had a project, and we stayed at the studio until 11 PM, and we called RISD Rides, and the van came, but I couldn’t fit my wheelchair in. The other students didn’t want to abandon me, so I suddenly had these three strangers waiting with me for an hour at night. It was late, and we all wanted to go home. I’m very thankful to them, too. It felt like a lot of people didn’t know about accessibility issues either, and it suddenly became a talking point: This is a problem that some people have.

AH: I feel like it was talked about and acknowledged when I forced it to be, which I had no shame in doing. But that confidence comes from being a senior, and having people I already knew and feeling in command of my experience at RISD at this point. I hadn’t felt that until very, very recently. I can’t imagine having had the confidence to advocate for myself before this time.

JK: It creates such a drop in self-confidence too … If you’re in a wheelchair, people always look down at you! This really got to my head. I never wanted to look good. I never dressed up. It really affected me mentally.

AH: I was a freshman in 2016 and then took time off, so I hadn’t eaten at the Met in two or three years, and suddenly it became the easiest way to feed myself. There were so many times I was just walking around the Met with my peg leg and I was like, I really don’t give a fuck. I’m only thinking about my needs. There is no other point in my RISD career where that would have been possible.

AW: Because it so dramatically forced you to trudge through and be seen?

AH: Yeah! And getting whatever I needed to get done was all I thought about.

JK: I felt that some days. But in the very beginning, it was like—first impressions! But near the end, when I was about to take the boot off, I was like, I really don’t care, I just want this to pass.

AW: Did you have moments of surrender, physically or emotionally?

JK: Yeah. I changed from a cast to a boot, and then RISD Rides wouldn’t come, so I just said "fuck it” and walked up the hill in my boot. And it sort of swelled up. So I just gave up on my injury and walked up the hill on my own. There were moments where I didn’t have time to wait.

AW: Do you come out of those moments feeling defeated or empowered?

JK: Well, empowered … and then it starts swelling. [laughter]

AW: What does it mean to have a broken ankle at RISD? How is a RISD broken ankle different?

JK: A RISD broken ankle is wanting to make art like other people and seeing people working so hard around you that you just sort of ignore that you have this broken ankle and continue to do everything you can.

AH: You just make it fucking happen.

JK: Somehow. “If there’s a will there’s a way.”

AH: Yep.

AW: RISD does prize self-sufficiency, but it really felt like there was no network of care? You were on your own?

JK: There’s kind of a network of care, but everyone has their own life, they have their own shit to do. No one’s going to baby me and care for me except for my family, and they’re not here, so it’s up to me.

AW: It feels sort of libertarian, survival-of-the-fittest …

AH: … in a very RISD way.

JK: You gotta do it all by yourself. It’s a wake-up call.

AW: Waking up into what world?

JK: The real world!

AH: I had an amazing network of support but it was just my friends. It wasn’t RISD, it was the relationships I had established. I had a couple of teachers who were really accommodating which was really helpful, but in terms of surviving around campus, it was mostly me with help whenever I could ask for it from people I love.

AW: I imagine there’s a world in which a student facing a physical disability thinks, “I actually couldn’t have gotten through this part of my life without some sort of institutional structure, a Public Safety team, some sort of administration looking out for me…” Were there spaces of refuge that only RISD could have provided you? Were there moments where you thought, thank god I’m at RISD?

AH: Public Safety only ever yelled at me for where I parked.

AW: What’s an ideal way for a school to allow disabled kids to move around?

JK: Ideally it’s flat.

AW: Bulldoze the hill.

JK: Just get rid of it! [laughter] I wish there were a better system for Public Safety. At the beginning of freshman year, they tell everyone to only call Public Safety if there’s an emergency, and everyone takes it really seriously. Me going to class or going home is not an emergency. If someone has a huge cut on their hand versus me trying to get a two-minute drive back to the quad—I obviously get it. I’m fine with getting picked up later, but I wish there were a system where disabled students could ask for what they need, fully knowing they would get the treatment they deserve. Like a car transportation program for a group of us, so we don’t always feel second.

AH: I understand that the physical landscape of RISD on the side of a hill is difficult, but basic things are so deeply inaccessible. I can think of maybe two handicapped buttons for opening doors on campus that work. I really struggled with opening doors and having to wait for people to open them for me. And RISD has so many old buildings. I couldn’t have gotten to this classroom [CB 302] in a wheelchair. The elevator lets off and then there’s more stairs to come down.

JK: All doors should have the handicapped door opener! I don’t know how expensive it is. But it’s crazy…

AH: We also need more staffing. The accessibility coordinator, in my experience, has been really helpful, but she has an enormous job and is in charge of accessibility for students with both physical and learning disabilities. Everything.

AW: What’s the biggest barrier to the accessibility conversation at RISD?

JK: The fact that accessibility affects such a small community of students. In my freshman year first semester, five or six people had some sort of boot or crutches or something. No one thinks it’s a big deal because it’s five out of five hundred students. Even for Orientation, no one thought someone would show up in a wheelchair. We had to sit on the RISD Beach but I couldn’t get there because there's a curb! No one thinks about that. It’s only something you realize once you’re in that situation.

AW: How do you view the space differently now?

JK: Well, I have to admit, now that I can walk and go anywhere, I don’t see these problems myself! Now I can get in every door. Like, oh, the billions of stairs up to the Met? I don’t care, I can walk up those stairs. When I was in a wheelchair, they were the most frustrating things ever. And now I don’t even realize because I can just walk up the stairs.

AH: It is crazy how as you heal these things you’ve become ultra aware of melt away. For a moment this felt really important to me, and I was horrified by how things were built, and now I’m getting back to my life.

AW: Do you view the Met differently?

JK: Yes! It feels different. I always had to use the Ozzi Box for take out, because there was no space for the wheelchair to fit there.

AH: Wait, like at the tables?

JK: Like at the tables. Too low. My studio finished at 6:00, when the Met was already full. There was nowhere to sit, so I’d ask for an Ozzi Box, but they were usually gone at that point. So I had no way to eat! But I love the people who work at the Met. They’re so nice, they’d be like, “Wait here,” and go wash one. Again, it’s all different now. I feel like I’m starting college over, like I just got to RISD again in the past couple of weeks.

AW: Are you reintroducing yourself? Do people see you differently?

JK: Dude, people see me so differently. I don’t tell people I was in the wheelchair, but I feel like all the freshmen saw me in the wheelchair at least once. I met this girl the other day and after we got closer, I mentioned it, and she was like, “No way, I was wondering where they went!” And I was like, “I’m right here.”

AW: They think you’re a different person.

JK: Yeah. They don’t know who I am. So I really do see everything in a new way. For a while it was what defined me—I was the only freshman in a wheelchair.

AW: How has the process of recovery and its timeline affected your semester? Is it overwhelming to suddenly see the campus in new ways?

AH: I just really recently started being able to take some little steps without crutches. It’s crazy how the moment you’re able to do that, so much opens up to you. It’s like every step is so much easier. Everything gradually gets simpler and simpler. Before, two steps was like a flight of stairs. I would decide not to go places because it would be too exhausting. I love Providence, and I also love walking. I used to walk so much every day, and it’s what allowed me to think. So just being able to walk places … is unbelievable. Obviously it’s different for people who live their lives with disabilities but I still don’t know how to function other than with my feet.

JK: It’s the small things. Like, Wow, I don’t have to wait for the elevator! I can use the stairs! I can do a lot more on my own. Most people are like, “Ugh, Thayer.” I’m like, “Wow, Thayer!”

AW: Do you think RISD’s architecture and infrastructure are reformable? Or do you think because of its campus RISD is doomed to be inaccessible?

AH: I don’t think it could ever be ideal. But it doesn’t even seem like they’ve really tried. There are a bunch of ramps on campus that aren’t actually handicap accessible.

JK: The ramps are too steep. They made me roll backwards.

AH: With my pegleg, I couldn’t go up inclines—I needed flat surfaces or an elevator. And constantly, whenever I asked for something, people would direct me to ramps. But they simply weren’t accessible to me. We need a more comprehensive understanding of the ways disability can function. This is a private design institution that we’re paying an enormous amount of money for and the needs of individual students need to be tended to—RISD needs more people who can take care of that.

JK: Bigger elevators would be good, too. In What Cheer my wheelchair barely fit in the elevator. They told me to twist and turn to fit in and somehow eventually I got in, but not without worrying about getting my legs chopped off by the closing elevator door. Maybe it’s expensive?

AH: It doesn’t matter if things cost money— accessibility should be the number one priority in terms of expenses. Like, why can you redo ProvWash and you can’t fix a ramp? And also fix those door-opening buttons. The stuff is there and they don’t even make sure it functions.

AW: So it feels like the means are there but solutions are not being implemented.

JK: The buttons are just decor.

AW: So you’re both at opposite ends of your RISD careers. How does having to confront this side of RISD frame your experiences with the school?

JK: I was shocked! I was like, “Oh, they don’t have anything for me!”

AH: It confirmed what I have slowly learned my whole time at RISD: there are so many good things and people here, but it’s mostly dependent on the individual’s ability to push through. A lot of things about RISD are confusing. With this experience it became clear how much I just need to get things done for myself—not just in terms of having a temporary disability but with so much … I never felt like RISD was my scaffold.

October 24, 2021

All in all, I’m extremely grateful for Public Safety’s help. I’d like to thank everyone who had to put the wheelchair in the car every day so I could go to class. I’m also super grateful to one particular Public Safety officer, who answered all my calls and memorized my schedule to help me get around. He put me in a good mood every day. In my EFS Spatial Dynamics class, my professor had us create a large-scale copy of any object. I decided to make a giant boot as an end to my broken ankle journey at RISD. —JK

All in all, I’m extremely grateful for Public Safety’s help. I’d like to thank everyone who had to put the wheelchair in the car every day so I could go to class. I’m also super grateful to one particular Public Safety officer, who answered all my calls and memorized my schedule to help me get around. He put me in a good mood every day. In my EFS Spatial Dynamics class, my professor had us create a large-scale copy of any object. I decided to make a giant boot as an end to my broken ankle journey at RISD. —JK

JK: I felt pretty low at first. I felt like the institution was like, “Either get through it or don’t come here,” but my professors were like, “I will help you no matter what.” I guess I saw the light in the professors, who I really admire. Now that I’m seeing all the holes that they need to fix, it definitely motivates me to speak up more for those who are disabled. My disability was only temporary, and this was only Providence. It’s a small school in a small city. I can’t imagine what it’s like in New York or LA or somewhere so much bigger where this is probably ten times as big an issue. I realized I need to say more.

AW: Does it feel like the conversation in itself is productive?

JK: It does, yeah. If you don’t ask for help and you don’t talk about your problems, nobody knows! So you have to bring awareness—nobody knows but us!

AH: What you said about specific professors being supportive and helpful is really important. I feel so grateful for the adults that cared.

JK: You can tell when they really care. It’s different.

In this exploratory conversation with Juri and Alex, I sensed their hesitance to speak too authoritatively about the experience of physical disability at RISD. Both were quick to point out that their injuries were only temporary setbacks, and none of us had experienced physical challenges beyond these two exceptions. The very limits of our experience begged the question as to why we hadn’t heard from more experienced voices in the first place.

Our conversation revealed just how little we as a student community know about RISD’s approach to physical disability, and we hope it can serve as a preliminary inquiry that sparks further discussion and action. Could it be true that those facing mobility challenges “just don’t go here”? What are the RISD Admissions messages and policies on this matter? What do other schools do? What are the quickest short-term solutions? (Door buttons... please!) What requires deeper investment? How can we reorient the campus—both physically and socially—to better serve students with physical disabilities?

In 2013, the artists Constantina Zavitsanos and Park McArthur wrote a series of compositional scores to be performed by two or more individuals. These choreographies of intimacy and awareness were inspired by the rituals of assistance that McArthur, who uses a wheelchair, requires from close friends and collaborators. Each one is gorgeous, at once a dance, a guided meditation, and instructions for care. My favorite is Score from Before VI. It opens with this set of gentle yet firm directives:

Look up the floor plan online.

Guess the width of the stairs.

Go to the site; imagine holding the weight of another body as you use the stairs up and down.

Express your worry.

Show up together.

Look at everyone looking at you with expectation.

Look back with expectation.

Feel the expectation of embodiment.

Reassure each other.

Accept help from others.

AW: Does it feel like the conversation in itself is productive?

JK: It does, yeah. If you don’t ask for help and you don’t talk about your problems, nobody knows! So you have to bring awareness—nobody knows but us!

AH: What you said about specific professors being supportive and helpful is really important. I feel so grateful for the adults that cared.

JK: You can tell when they really care. It’s different.

In this exploratory conversation with Juri and Alex, I sensed their hesitance to speak too authoritatively about the experience of physical disability at RISD. Both were quick to point out that their injuries were only temporary setbacks, and none of us had experienced physical challenges beyond these two exceptions. The very limits of our experience begged the question as to why we hadn’t heard from more experienced voices in the first place.

Our conversation revealed just how little we as a student community know about RISD’s approach to physical disability, and we hope it can serve as a preliminary inquiry that sparks further discussion and action. Could it be true that those facing mobility challenges “just don’t go here”? What are the RISD Admissions messages and policies on this matter? What do other schools do? What are the quickest short-term solutions? (Door buttons... please!) What requires deeper investment? How can we reorient the campus—both physically and socially—to better serve students with physical disabilities?

In 2013, the artists Constantina Zavitsanos and Park McArthur wrote a series of compositional scores to be performed by two or more individuals. These choreographies of intimacy and awareness were inspired by the rituals of assistance that McArthur, who uses a wheelchair, requires from close friends and collaborators. Each one is gorgeous, at once a dance, a guided meditation, and instructions for care. My favorite is Score from Before VI. It opens with this set of gentle yet firm directives:

Look up the floor plan online.

Guess the width of the stairs.

Go to the site; imagine holding the weight of another body as you use the stairs up and down.

Express your worry.

Show up together.

Look at everyone looking at you with expectation.

Look back with expectation.

Feel the expectation of embodiment.

Reassure each other.

Accept help from others.

Juri Kang wants to create sustainable and accessible work for everyone.

Alex Hoffman is doing their best.

Asher White has stopped rollerblading for the time being.

Editors’ note: Before publication, we asked Jack Silva, Vice President, Campus Services, and Mollie Goodwin, Academic Disability Specialist, to read this interview and let us know if he wished to offer corrections or comment. We thank him for his response:

Thank you for your thoughtful article regarding access on the RISD campus. I share the concerns you raise, and my team and I are committed to improving accessibility. It is a primary focus in our daily work, and also a priority as we plan for new construction and renovations. For example, most recently, the residence hall construction and renovations included door opening systems, ramps and elevators, along with other code improvements.

The examples you shared and descriptions you offered are important information for us to hear as RISD moves forward with both the Strategic Plan and Campus Master Plan. If others in the community have suggestions or observations, I would appreciate the feedback anytime. My email is jsilva@risd.edu.

***

Thank you for your thoughtful comments regarding accessibility at RISD. RISD Disability Support Services and Facilities continue to work in collaboration to make our campus as accessible as possible. All projects completed will be compliant with the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) and as buildings get renovated accessibility updates are made. If you have any campus accessibility concerns please contact Disability Support Services at 401 709-8460 or disabilitysupportservices@risd.edu. Concerns or questions about physical accessibility can also be submitted directly to the Department of Facilities Management through their work order request form at workorders.risd.edu.