Seeking Fair Game on Hidden Fields

Reilly Blum

→ BFA FD 2020

Illustration by Ian Williams (BFA IL 2021)

Illustration by Ian Williams (BFA IL 2021)I was recently duped into ordering several pints of Ben & Jerry’s ice cream through a low-fi, emoji-driven delivery-service app called goPuff. Despite the fact that I live a 12-second walk from a store carrying everything I could ever want to order from the app, the pretense that I would receive $15 off my first purchase made me feel like I was winning something.

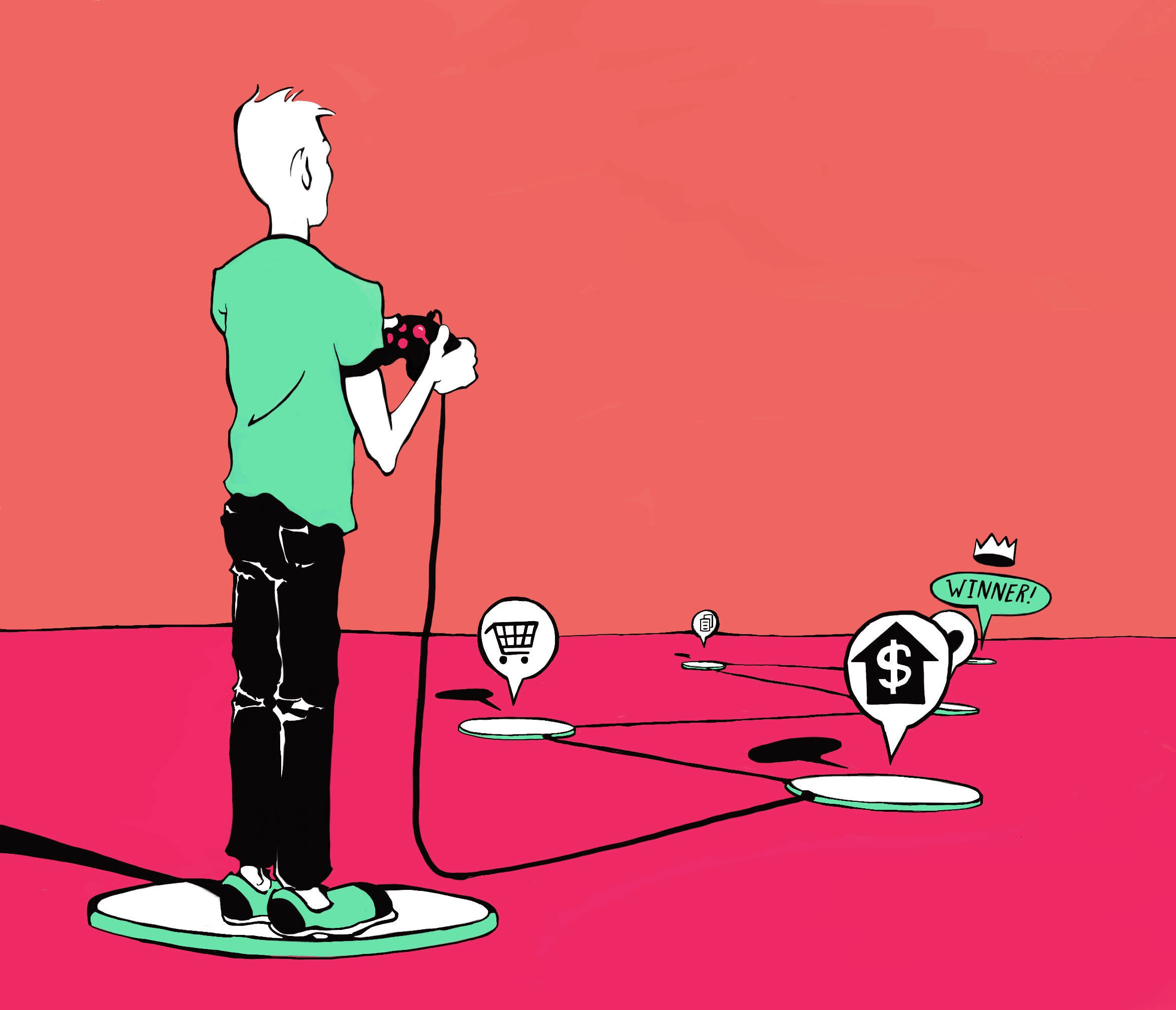

Games are an inextricable part of our culture, so inseparable from more “serious” pursuits that we have embedded game structures into areas of life traditionally unrelated to play. This process, known as gamification, has proven an effective strategy across disciplines. Elements of game design (such as point- or reward-value systems) crop up in credit card rewards, vocabulary study, advertisements, language-learning apps—even news and media sites leverage game-based mechanics to optimize reader engagement. Mashable.com, for example, employs a social engagement system called Mashable Follow that rewards users badges for commenting on articles, connecting other social media profiles to their Mashable accounts, and actively participating in the site’s discourse. It isn’t too far of a leap to suggest that virtual social systems hold sway because their quantified engagement (5 likes, 2 shares, 7 followers, 1 mention, 3 matches) gives us a sense of gaining points. If we reduce social relationships to metric systems buoyed by the reality that numbers have social clout, aren’t matches or retweets a sort of prize, and isn’t the whole internet a sort of game? Games are inescapable, but what happens when we no longer know that we’re playing?

Within 40 minutes of first encountering goPuff’s highly localized and specifically targeted Instagram ad, the game was set. Gone was my lingering guilt over instantaneous submission to capitalism and gone was my disappointment at being so easily swindled by an algorithm; I was making significant progress on a pint of The Tonight Dough. Somehow, being aware of the fact that I’m being duped, and then consciously deciding to submit to the duping, negates the original trickery by making me feel like I have the upper hand. The best part? The prize I received for making that purchase: 30 Puffpoints, which I may save or instantly redeem for free items. Currently I have enough points to purchase a bottle of Bic Eco-Friendly White Out or one Lindt Lindor Milk Chocolate Truffle.

There’s something about existing in a very silly, ironic/post-ironic/post-internet/post-truth/post-intellectual/image-based/content-driven/low-fi/hi-tech/socially quantified culture that makes me shockingly irrational. Maybe I’ve been poisoned by the internet, or maybe I just love to win. Either way, goPuff provided a diversion from more pressing unpleasantries such as Reading Response Week 4. And at the end of the day, I don’t think the app’s structure and arguably hypnotic interface is all too different from games and apps that have much greater cultural sway: Candy Crush, Subway Surfers, Angry Birds, and, by extension Instagram, Facebook, Snapchat, Twitter, Tinder—even my mobile banking app gives me prizes when I spend money. All of these systems promise both short- and long-term rewards for completion of relatively simple tasks.

Task-reward or otherwise gamified systems are highly effective in helping us commit stimuli to memory because they act as immediate applications of knowledge. Unless we partake in a (largely involuntary) system of cerebral cherry-picking, we lose the vast majority of the information we intake. Because we can only perceive so much, games help our brains filter information by diversifying the modes through which stimuli may be processed. Educational theorists suggest that gamified lessons may increase students’ absorption of new information; the same holds true for any breed of engaging and immediately gratifying diversion, whether it’s a mind palace à la Sherlock Holmes, a vocabulary game, or a targeted ad that lures you into buying several pints of ice cream you don’t need. A 2013 report suggests that gamification is effectively a study in behavioral economics and that this system becomes effective through an understanding of its target audience and context.1 For sometimes better but more often worse, advertising is a practice that totally usurps consumer logic. Perhaps the most potent proof of this is that recognizing or being aware of manipulative commercial practices does not necessarily lessen their power.

A recent study on developmental cognitive neuroscience suggests that human attention is “malleable,” insomuch as it lengthens and shortens in different environments.2 The study posits causal evidence that engaged and purposeful play may shape the bounds of human attention. In this instance, frequent players of video games (as compared to a control group) displayed enhanced attention in certain scenarios and were better able to filter irrelevant information. Companies and technology moguls are profoundly aware of the limits of human attention, and games, long used to help us remember our multiplication tables or to while away an afternoon, have eclipsed the realm of play to enter the realm of capital. And while capital gain can be distinct from user benefit, gamified advertisements—geared toward young, internet-poisoned minds such as mine—can cause even the most sensible and rational person to mindlessly absorb coded information. If game structures truly do augment the way we take in and file new information, how should we react when our attention is being actively sought after and monetized?

While the experience of play is characterized by its lack of practical applicability, games necessarily partake in a set of established rules or structures. Play is a social and evolutionary necessity: it’s how we experience alter-realities and take actions without undergoing any personal or social risk. Gamified experiences are distinct from play insomuch as they rely upon either an understood purpose or an application of some sort: they are pseudo-games that exist only to serve a larger system or purpose. While exploitation of the human need for play isn’t necessarily a bad thing (NikeFuel, for example, arguably promotes more active lifestyles by creating a network through which users compete on regular personal fitness challenges), our culture’s insistence upon metrics as a useful social tool, when conflated with gamified social systems, cannot be healthy. How many of our day-to-day interactions and decisions are implicitly guided by the potential of “winning” a game (real or imagined)?

In application, gamification typically reduces the complex experience of play into a simplified point system that lacks significant interpretability—a credit card rewards system, for example, does not truly mimic the strategy or intellectual rigor of sport. And while it may be dangerous to operate under the implicit assumption that certain games or modes of play are intellectually superior to others, I’m hard-pressed to find any sort of larger interpretability for most of the tournaments in which I partake on a day-to-day basis. Maybe Monopoly implicitly encourages players to penny-pinch, but what has Candy Crush done for society? If social interactions, educational practices, and economic transaction have entirely embraced the model of the game, does there still exist a reality totally distinct from simulacrum, or does the question of gamified systems become a moot point altogether? Or, rather, has the system become the game itself?

goPuff now lives in my “important essentials” folder, next to Gmail, Messages, Spotify, and Maps. While eating that fateful pint of The Tonight Dough, I began to wonder if operating within a totally gamified socioeconomic system is ultimately destructive, or, rather, whether one’s own elimination, agitation, ruination, liquidation, invalidation, mindless preoccupation, et cetera, is made both inevitable and sickeningly pleasurable through participation in a tournament, series of tournaments, or challenge of which you are both a co-conspirator and a player. Despite the fact that it effectively exploits human psychological weakness, I’m not sure whether or not this “destruction” is necessarily a moral evil. If I’m having fun and a corporation is having fun, perhaps gamification suspends morality altogether. Maybe I’m putting too much stock into the advertised microgame, or maybe I just have network fatigue. Of course, that doesn’t change the fact that, for reasons which I would like to believe are beyond my control, there is very little space in my freezer.

1 Wendy Hsin-Yuan Huang and Dilip Soman, “A Practioner’s Guide to Gamification of Education,” inside.rotman.utoronto.ca/behaviouraleconomicsinaction/files/2013/09/GuideGamificationEducationDec2013.pdf

2 Courtney Stevens and Daphne Bavelier, “The Role of Selective Attention on Academic Foundations: A Cognitive Neuroscience Perspective, sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1878929311001101

Reilly Blum dreams in pixels.