How to Become Trans: A Proposal for the Modern-day Gender-agnostic

How to Become Trans: A Proposal for the Modern-day Gender-agnostic

Asher White

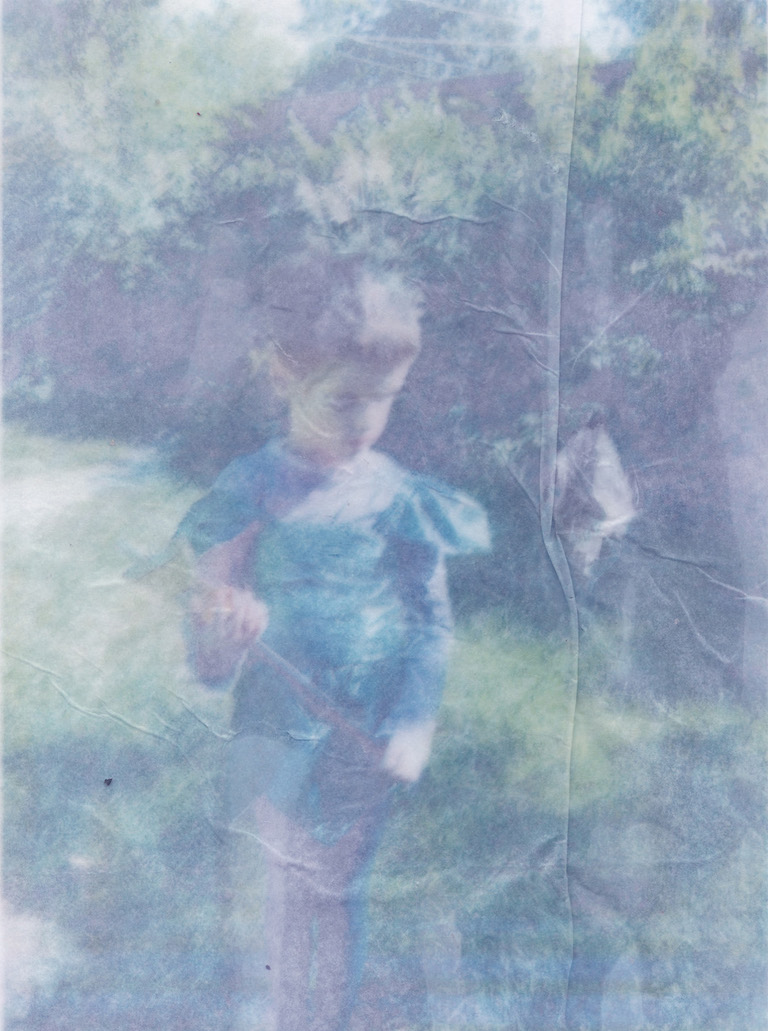

Asher as Tinkerbell (or Tinkerbell-adjacent generic brand fairy), 2005. Photograph by Shari Joffe.

Asher as Tinkerbell (or Tinkerbell-adjacent generic brand fairy), 2005. Photograph by Shari Joffe.I suppose there’s a chance I’m totally fabricating this memory in retrospect but as far as I’m concerned, I can vividly picture myself in 1st grade, explaining to a friend’s mom that I was going to cut my dick off. I can remember that grimy afternoon exhaustion, the nauseating wheeze of the swingset, the dry, sunbaked wood-chip smell. I can’t remember the order of the planets in our solar system but I can remember professing my plans for sex reassignment surgery, so apparently my brain has selectively preserved my finest moments and overridden the useless ones.

I spent 15 years—78% of my life as of now—as a boy, occasionally really leaning into it, frequently straying from it, and constantly bewildered about how I was going to operate under it. I consoled myself, deciding that I was just gay, or artsy, and that gay and artsy boys have such a fundamentally different experience of boyhood that it was well within character to feel entirely alienated from the rest of the boys. I was just a different “shade” of boyhood.1

It took one year of high school for me to discover that boyhood—no matter the shade—was getting in the way of me being Asher, and that boyhood impeded the potential of Asher, and that continuing as a boy would produce a mangled and incomplete version of Asher. Even the model of highly feminine boy felt like only a crude imitation of what I wanted to be: “femme-boy” was closer aesthetically, but neglected to fully capture the energy of womanhood.

It was after a year of high school that I finally discovered girlhood actually opened a lot more doors for Asher, and the tools of girlhood were the tools I could use to expand and develop the Asher I could be. Plus, the new cultural baggage of 21st-century American womanness (intellect, sarcasm, sensitivity, mischief, floral patterns)2 was promising. It makes sense that the music3 and art4 I fell in love with at that time all seemed to offer paths beyond Man and Woman.5

I’ve now effectively been a (flourishing) woman for almost five years, and it’s become clear to me since “crossing over” that my experience of boyhood—the years “before,” the dark past—is a chapter of the story that is supposed to be left untold. The popular trans narrative is that trans women are “women born in the wrong body” and trans men are “men born in the wrong body.” To me, this is horrifyingly regressive. It only furthers ideas of gender essentialism, like: “you can be innately man or innately woman," which is the type of cosmic-categorization that we're trying to liberate ourselves from.6

Andrea Long Chu, brilliant and revolutionary trans writer (to whom this essay owes an unreasonable amount) wrote a fearless article on transwomanhood (for magazine n+1, the blinding beacon of millenial social criticism) that breathes more nuance into the conversation than really anything else I’ve read.7 She dives headfirst, totally unafraid, into the most uncomfortable discussion in transness: How do we acknowledge our experiences as the first gender assigned to us? And how do we extend beyond those? What does it mean to be a trans woman, and what does it mean to be a woman at all?

As I’ve talked with people more and more (particularly cis women), I’ve discovered that this idea of gender as “pursuit”—of striving—is a lot more common than I thought. The most resolutely feminine empowered women I know all find a supreme amount of power in their choice to identify with womanhood, and their pursuit of divine femininity.

So I’ve sought to find new working terms that ideally can provide some clarity amidst the dense fog of gender discourse: diagnostic and aspirational gender. These terms mark my attempt to: a) discern the multiple relationships to gender in each of us individually, and b) fulfill my lifelong fantasy of Coining New Terms.

Diagnostic gender is the process of “running tests” that characterize how gender operates in your life. Like a Buzzfeed personality quiz, your diagnostic gender doesn’t reveal any “truth” about who you are, but can provide insight into your identity as it stands at the time of the test. How do you talk to men? How do you talk to women? How do you speak in a room? Do you listen to more music by male or female artists? What color schemes, patterns, architecture, etc., are you naturally drawn to? In what groups do you feel most comfortable? More often than not, these are determined by whatever gender was foisted upon you, but also would be influenced by your childhood experiences, parental relationships, media socialization, etc.

Aspirational gender is the process of choosing the gender you identify with—the set of attitudes, ethics, and aesthetics that you admire and want to embody. It is the vow of reaching towards Manhood or Womanhood. What qualities do you admire in people? What do you strive to be like? Who represents strength and power to you? Who represents success?

To place this in context: Transphobia is the belief that gender is determined by one’s genitals, and both diagnostic and aspirational gender are bogus. The most popular understanding (which is casually transphobic) is that gender is determined by a combination of one’s genitals and diagnostic gender—i.e., how you “seem,” sound, dress, act. The idea of aspirational gender as legitimate identity is rarely accepted. In other words, most generally feel that the spiritual quest of ideals does not actualize those ideals.8

Andrea Long Chu believes the opposite: that aspirational gender is all there is—that any diagnostic work is inevitably clouded by our aspirational biases, and the reach for Womanhood is in fact Womanhood. This would mean that cis men are ontologically men only because each day they strive to be men, and were they to suddenly subscribe to Womanhood, they would cease to be men.

Chu’s ideas are radical, and I ultimately think there’s a little more to occupying a gender than striving towards an ideal—that operating as a woman doesn’t just mean wishing you were a woman, but actualizing those desires. To live as a woman means to directly engage with Womanhood, to interpolate the attitudes, aesthetics, and ethics of Femininity—according to your culture/community—into yourself. Just as being a Goth means participating in Gothdom, being a woman means participating in Womanness: listening to other women, supporting the work and art and lives of other women, contributing to the universe of Women. That means considering the aspects of yourself riddled with “manness” and rethinking what you have to offer womanhood.

Could it be? Is this it? The Conservative nightmare of Leftist cucks Goldilocks-ing through gender to find what’s “just right”? It doesn’t take long into any conversation with an open transphobe to discover that they are just as terrified and frustrated with their assigned identity as anyone—they’ve just nullified the possibility of growth or critical re-thinking.9

The astrology-app wisdom of “be the best You that you can be” doesn’t seem radical until it’s placed in the context of gender, and then it’s potentially revelatory. Is the gender you were assigned at first conducive to you being the most dimensional version of yourself? Really? Think of you, but without that gender, and consider the possibilities that genderlessness / the opposite gender would award you. Maybe it feels fruitful. Maybe it doesn’t. You don’t have to be trans, but you should probably consider it, and if you identify as cis, you should carefully examine why. The most frustrating trans issue is the tendency of cis people to exempt themselves from the “gender identity” debate. It’s like declaring yourself apolitical. To be a gender agnostic to is to safely distance yourself from confronting or challenging your notions of gender—in yourself and others. If we are to develop richer and more critical understandings of how gender operates, everyone has to investigate their relationship to gender: asking both what you’re doing for your gender and what your gender is doing for you.

1. The designation of me as a “girly boy” was actually probably the biggest roadblock in the highway to womanly bliss; while seemingly innocuous, it was probably the most destructive identity that could’ve been ascribed to me. It taught me that regardless of my behavior, regardless of my interests or aesthetics or attitudes, I could only modify boyhood—“boy” was the resolute class, and though I could accessorize or addend or even amend, I was only qualifying my boyhood, not transcending it. It took me years to figure out I didn’t have to be a “girly boy”—I could just be a girl.

2. These formative years were also the first 15 years of the 21st century, when the media’s goblet ranneth over with manic pixie dream girls, whose irreverence and boldness felt like beacons of my potential. I understand this raises some red flags about who I am as a person but Zooey Deschanel, Eternal Sunshine-Kate Winslet, the girl from Bridge to Terebithia I think, maybe Because of Winn-Dixie … all of these independent, fearless young female protagonists were exactly who I wanted to be. Also, weirdly (and much earlier), I identified really strongly with Junie B. Jones.

3. The 1992 masterwork Pop Tatari by Japanese freak-psych noise-rock act Boredoms offers a universe liberated from the oppressive structures of really everything, where the human body can spit and gag and warp and twist, and drums can explode and then kind of skitter away, guitars can sting and pop . . . throughout the album, the gravity is doubled, reversed, removed. The utopian chaos of Pop Tatari uses preconceived notions we bring to the band— “rock,” “Japanese,” “female-fronted,” “experimental,” etc.—and plays them to their advantage. There’s crude, half-remembered Ramones parodies, piercing electronic feedback, Parliament-Funkadelic-esque funk dirges, fart noises, and hundreds of drum tracks stacked on top of each other. It’s the sound of a band revelling in the possibilities of sound and our expectations. It’s the least listenable party record of all time. It rules.

4. Egon Schiele’s grotesque, unflinching portraits of male and female subjects alike shows a pretty striking refusal to discern gender; he just kind of drew everyone like carcasses, and his androgynous self-portraits—blue-lipped and eye-shadowed—are the nail in his trans coffin. He was thinking about the body as little more than a body.

5. I’m leaving out a glaring aspect of my childhood experience with gender, which was the consistent and unbearable pain of not having a vagina. It’s crucial to distinguish gender dysphoria from body dysphoria: gender dysphoria is a disillusionment with gender, feeling constricted by the constructed gender binary; body dysphoria is a disillusionment with your body itself, feeling imprisoned by your genitalia (not to be confused with body dysmorphia, which is a distorted perception of how one looks). There are plenty of trans people who only experience gender dysphoria and not body dysphoria, who love their bodies but hate the way they’re perceived. Unable to divorce the concept of womanhood from the vagina, I grew up despising my penis and understanding it as an immovable obstacle that would prohibit me from womanhood. While I’ve been mostly successful at reframing both womanhood and the penis, there will always be a part of me that is tormented by my naked body, and I will have to live (and die) knowing that I was “born in the wrong body.” That sucks. (I remember attaching a lot of this dreadful emotional baggage to the phrase “YOLO,” because it brought me to realize that my one shot at life—I only live once!—was squandered by my body, and after this I will be dead forever, never having reached satisfaction with my body.)

6. Every trans woman has spent time as, ontologically, practically, a boy, and every trans man has spent time as a woman. Not because it's what they “innately are," but because it is how they were treated, socialized, and what they knew to be true at the time. This is a terrifying thing to admit, but in fact, acknowledging that I understand many of the experiences of boyhood is the best jumping off point for how I can emphasize how much of a woman I am. Those disorienting experiences of expectation and inadequacy are ultimately really useful for approaching gender going forward. Why would we dismiss them and pretend we don't know what it's like to be a boy? Our superpower is that we do know what it's like to be "the other one!"

7. Andrea Long Chu, “On Liking Women,” n+1, January 3, 2018, nplusonemag.com/issue-30/essays/on-liking-women/.

8. This is bonkers, because the world was split, destroyed, and rebuilt by people reaching for divine Christianity without ever “embodying Christ,” and every religion is built around faith that our objectives of what we want to be like are what define us.

9. A foundational pillar of inceldom is the horror of their own male inadequacy, the dread of scaling up to the male standards around them, i.e., gender dysphoria. There’s no other hate group that so brashly declares and brandishes as a weapon their own fear and inadequacy. There’s a unique absence of “supremacy” rhetoric in reddit inceldom that distinguishes it from neo-nazis, white supremacists, etc.: incels wallow and fester in their inferiority, before weaponizing it against women. The recurrent use of the “Chad” figure, a symbolic character who embodies the male ideal (blonde, buff, sexually proficient, care-free, confident), as well as his female counterpart, Stacy, demonstrates their resentment towards the gender binary. Incels fail to consider that the reason they will never be Chad is not because they were mysteriously cursed by the cosmos and banished from the kingdom of manness—it’s probably because the Ultimate Male identity just isn’t right for them.

Asher White is not undergoing hormone therapy, but she does drink a carton of Silk Soy Milk a day for the slight estrogen boost. She is also wondering if she has exceeded the age threshold for wearing velcro-strap shoes.