Accessing Color: Dissecting the Harvard Art Museum’s Forbes Pigment Collection

Makoto Kumasaka

→ BFA FD 2019

Edward Waldo Forbes was instated in 1909 as the director of the Fogg Museum at Harvard University, where he set out to develop one of the first laboratories devoted to the scientific study of art materials and their applications. Within the Department of Research and Restoration, Forbes assembled material collections from around the world with the aim of investigating art forgery. Over several decades, the collections grew under Forbes’s voracious patronage, and the most prominent collection was eventually named in his honor: the Forbes Pigment Collection.

![]() The Straus Center for Conservation and Technical Studies in the Harvard Art Museums’ Forbes Pigment Collection.

The Straus Center for Conservation and Technical Studies in the Harvard Art Museums’ Forbes Pigment Collection.

Today, the Department of Research and Restoration is known as the Straus Center for Conservation and Technical Studies. Still housing the Forbes Pigment Collection, the center is located on the top floors of the Harvard Art Museums’ glass-capped Calderwood Courtyard. I first learned about the Pigment Collection while conducting research for a design charrette on a cross-disciplinary laboratory dedicated to the study of color. I read about Renzo Piano’s 2014 redesign of the museums and his plans to create a space that was “open to the city and to the light.” Piano rendered the museum courtyard space as an atrium. For the average museum patron, the collection exists as a flirtation of rainbow pigment vials just visible beyond a dazzling field of glass.

Around the turn of the 21st century, Australian conservation researcher Narayan Khandekar joined the research team and initiated a program to extend the collection to include three thousand synthetic pigment colorants. Around this time, in 2007, the lab conducted a pivotal investigation corroborating the forgery of three Jackson Pollock paintings. Thanks to Khandekar’s efforts to modernize the collection and this investigative study, the Forbes Pigment Collection has appeared in mainstream publications—the New Yorker, Hyperallergic, and Fast Company, to name a few—and drawn a growing number of visitors interested in catching a tour.

At the moment, one of the challenges facing the Straus Center is a lack of structure to accommodate this surge of interest. According to Peter J. Atkinson, the Harvard Art Museums Director of Facilities, the placement of the collection was, in large part, a default decision. Given a limited amount of space, the cabinets were siloed into a narrow hallway, only accessible to the public for close inspection through scheduled tours. This interaction with the Pigment Collection is reminiscent of early anatomy theaters, in which an educator stood at a central table and performed dissections of human or animal bodies. Viewers were allowed only one point of entry—through the instruction of the performer.

Architecture has a long history of balancing the needs of specialists and laypeople. In the early 1500s, “memory theaters” allowed philosophers to present thoughts or “memories” to an audience through methods rooted in the occult and allegorical, organizing content into amphitheatrical shapes. This architectural phenomenon signaled a shift in the understanding of the structure of the universe. A collective reconsideration of celestial order that began in the Enlightenment came to bare in the design of intellectual and educational spaces.

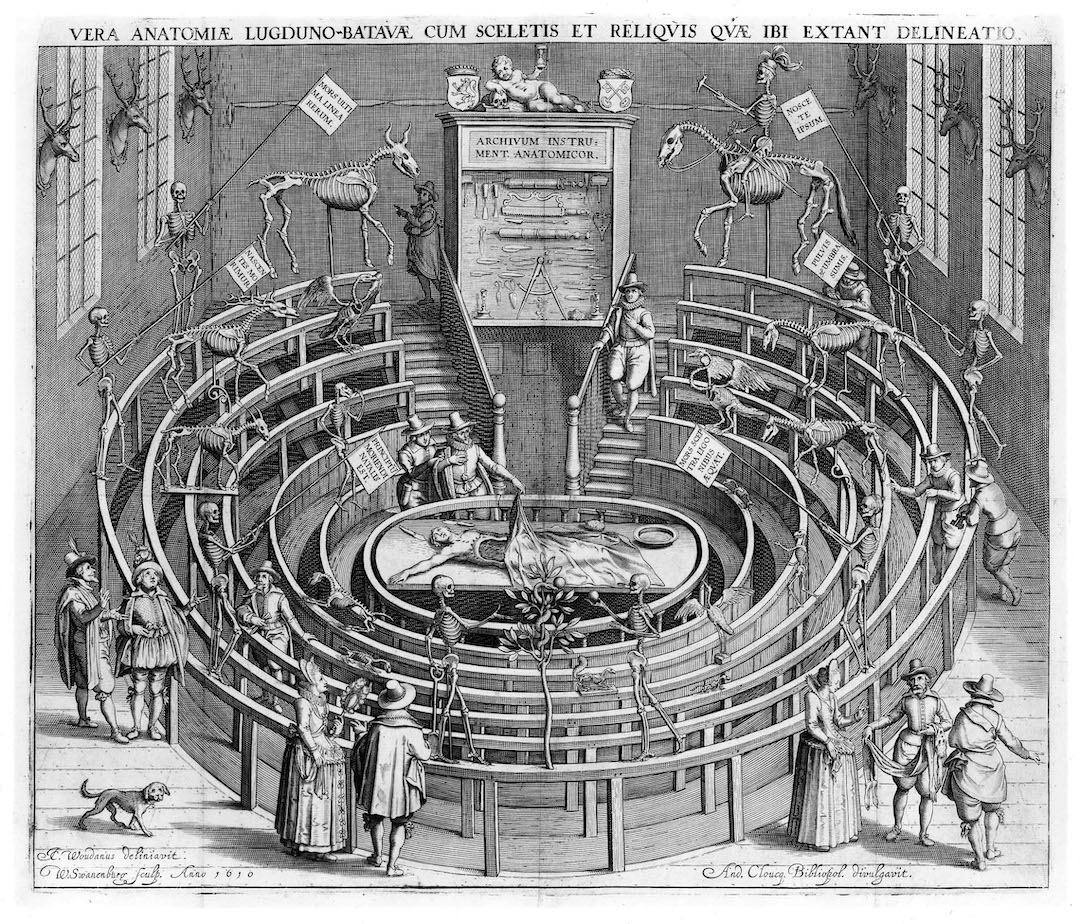

![]() Leiden Anatomy Theatre, engraving by Willem Swanenburgh, circa 1610. Image from Wikimedia Commons.

Leiden Anatomy Theatre, engraving by Willem Swanenburgh, circa 1610. Image from Wikimedia Commons.

The Straus Center for Conservation and Technical Studies in the Harvard Art Museums’ Forbes Pigment Collection.

The Straus Center for Conservation and Technical Studies in the Harvard Art Museums’ Forbes Pigment Collection.Today, the Department of Research and Restoration is known as the Straus Center for Conservation and Technical Studies. Still housing the Forbes Pigment Collection, the center is located on the top floors of the Harvard Art Museums’ glass-capped Calderwood Courtyard. I first learned about the Pigment Collection while conducting research for a design charrette on a cross-disciplinary laboratory dedicated to the study of color. I read about Renzo Piano’s 2014 redesign of the museums and his plans to create a space that was “open to the city and to the light.” Piano rendered the museum courtyard space as an atrium. For the average museum patron, the collection exists as a flirtation of rainbow pigment vials just visible beyond a dazzling field of glass.

Around the turn of the 21st century, Australian conservation researcher Narayan Khandekar joined the research team and initiated a program to extend the collection to include three thousand synthetic pigment colorants. Around this time, in 2007, the lab conducted a pivotal investigation corroborating the forgery of three Jackson Pollock paintings. Thanks to Khandekar’s efforts to modernize the collection and this investigative study, the Forbes Pigment Collection has appeared in mainstream publications—the New Yorker, Hyperallergic, and Fast Company, to name a few—and drawn a growing number of visitors interested in catching a tour.

At the moment, one of the challenges facing the Straus Center is a lack of structure to accommodate this surge of interest. According to Peter J. Atkinson, the Harvard Art Museums Director of Facilities, the placement of the collection was, in large part, a default decision. Given a limited amount of space, the cabinets were siloed into a narrow hallway, only accessible to the public for close inspection through scheduled tours. This interaction with the Pigment Collection is reminiscent of early anatomy theaters, in which an educator stood at a central table and performed dissections of human or animal bodies. Viewers were allowed only one point of entry—through the instruction of the performer.

Architecture has a long history of balancing the needs of specialists and laypeople. In the early 1500s, “memory theaters” allowed philosophers to present thoughts or “memories” to an audience through methods rooted in the occult and allegorical, organizing content into amphitheatrical shapes. This architectural phenomenon signaled a shift in the understanding of the structure of the universe. A collective reconsideration of celestial order that began in the Enlightenment came to bare in the design of intellectual and educational spaces.

Leiden Anatomy Theatre, engraving by Willem Swanenburgh, circa 1610. Image from Wikimedia Commons.

Leiden Anatomy Theatre, engraving by Willem Swanenburgh, circa 1610. Image from Wikimedia Commons.Over the course of centuries, the utilization of space to convey knowledge has evolved, with an increasing emphasis on explorative and autonomous viewing experiences. Many modern collections operate on principles of kinesthetic learning, immersing visitors in a subject matter, literally and physically, in an attempt to shift the viewer from a passive observer to an active learner. RISD’s Nature Lab, for example, is composed of a disparate array of collections related to the natural world, and accommodates a wide variety of technical laboratory equipment with the intent of fostering a hands-on learning environment that explores the connections between art, design, and science.

In many ways, the inaccessibility of the Pigment Collection’s content can be addressed through its design. Signage, audio tours, and including the Straus Center in the museum’s wayfinding systems (curiously enough, the Straus Center cannot be found on current museum maps) could prove effective in fostering a more active relationship between the public and the Pigment Collection. The vitrine installed opposite the Art Study Center reception desk, perhaps the most accessible aspect of the Collection, could be expanded to include a larger array of pigments and convey more information about the contents and history of the collection. These changes also have the potential to liberate employees from the tasks of providing guided tours and deliver a more autonomous viewing experience to museum patrons.

It is never enough to simply instigate a design intervention and walk away. Maintaining an effective display for public education requires constant critical evaluation and targeted adjustments. In his 2005 article “Objects and the Museum,” the theorist Samuel J. M. M. Alberti argues for the importance of more focused research on museum patrons and the development of human-centered designs. For spaces like the Forbes Pigment Collection, the implementation of intelligent design alterations that deliver autonomy to museum visitors are integral to its continued existence. As rumors begin to suggest the development of a RISD Color Lab, we, too, have an opportunity to imagine how students, faculty, and visitors might engage with the study of color.

In many ways, the inaccessibility of the Pigment Collection’s content can be addressed through its design. Signage, audio tours, and including the Straus Center in the museum’s wayfinding systems (curiously enough, the Straus Center cannot be found on current museum maps) could prove effective in fostering a more active relationship between the public and the Pigment Collection. The vitrine installed opposite the Art Study Center reception desk, perhaps the most accessible aspect of the Collection, could be expanded to include a larger array of pigments and convey more information about the contents and history of the collection. These changes also have the potential to liberate employees from the tasks of providing guided tours and deliver a more autonomous viewing experience to museum patrons.

It is never enough to simply instigate a design intervention and walk away. Maintaining an effective display for public education requires constant critical evaluation and targeted adjustments. In his 2005 article “Objects and the Museum,” the theorist Samuel J. M. M. Alberti argues for the importance of more focused research on museum patrons and the development of human-centered designs. For spaces like the Forbes Pigment Collection, the implementation of intelligent design alterations that deliver autonomy to museum visitors are integral to its continued existence. As rumors begin to suggest the development of a RISD Color Lab, we, too, have an opportunity to imagine how students, faculty, and visitors might engage with the study of color.

Makoto Kumasaka enjoys the middle ground.