Best! A Critical Review of Queen Elizabeth Olympic Park

Julæ Tan

→ MLA LDAR 2026

Singlish terms (in order of appearance)

Best

Horrigible

Blur like sotong

Gabra like zebra

Stunned like vegetable

Malu

Powderful

A distortion of the English word “powerful” that alludes to the ephemeral qualities of powder. Oft used in the phrase: “your England berry powderful hor!”

Gong simi

Rojak

![]()

Singlish, a portmanteau of the words “Singapore” and “English”, is an English-based creole language spoken primarily in Singapore, the entrepôt city-state in Southeast Asia that was once a British colony. The language contains combinations of vocabulary, turns-of-phrase and sentence structure from English, Mandarin, Malay, Tamil, Hokkien, Cantonese, Teochew, and Japanese, among other languages that are spoken by residents in the country. From my empirical understanding and academic research, Singlish is an elaboration of a pidgin language used between non-native English speakers as a means of communication in professional and social settings (Ong, 2017). The thread of pragmatism as well as commerce is as ingrained in the psyche of Singaporeans as it is in Singlish. Various ethnic groups were brought into the country by the British to serve various economic roles and to maintain social division and control (Chua, 2003). While most residents of the country are multilingual, Singlish serves as the de facto lingua franca.

Singlish syntax is consequently optimised for efficiency. For instance, instead of saying, “Why is it like that?”, Singlish speakers boil sentences to their essential elements, conjoin prepositions with adjacent pronouns, and inject emotion to form elegant syntactic structures: “Why liddat?” (Gwee, 2018).

End particles in Singlish are also immensely powerful and convey considerable meaning and emotion with minimal effort. Take the following set of expressions that convey increasing levels of frustration at a tricky situation.

“How leh?” — [curt, inquisitive, pleading] an earnest, curious ask for direction

“How ah?” — [medium, curious, slight annoyance] slightly frustrated plea for help

“How?” — [long, pleading voice] conveys an earnest plea for help in an unfortunate situation

“How sial?!” — [said like an expletive, sometimes with an ironic laugh] conveys intense frustration in a desperate plea to save an irrevocably bad situation

“How can?” — [desperate, said with intensity in each word] “How can this be allowed?”

Unlike Olympic Park, Singlish combines a gamut of influences to form elegant expressions of efficiency and pragmatism. Malu!

In Singlish, “Best” is oft deployed as an ironic exclamation of comedic failure.

Horrigible

A portmanteau of the English words “horrible” and “incorrigible”, implying that a horrible situation is beyond

redemption.

The word improves on the English word “horrible” semantically and aurally and “bears a Gothic weight of disgust” (Gwee, 2018).

The word improves on the English word “horrible” semantically and aurally and “bears a Gothic weight of disgust” (Gwee, 2018).

Blur like sotong

Animal and plant-themed similes are common in Singlish. “Blur like sotong” translates literally to “confused

like a squid”, “sotong” being squid in Malay.

Gabra like zebra

Similar to “blur like sotong”, “gabra like zebra” denotes

a frazzled confusion. This simile is less clear and likely

popularised due to the rhyming of “zebra” and “gabra”.

Stunned like vegetable

An overnight addition to the Singlish lexicon: this

phrase is a lyric from a faux-retro music video released

in 2015 featuring the Chinese actor Chen Tianwen

serenading his lover whilst whipping out a bouquet and

broccoli.

Malu

Means “shame” in Malay.

Powderful

A distortion of the English word “powerful” that alludes to the ephemeral qualities of powder. Oft used in the phrase: “your England berry powderful hor!”

Gong simi

This Singlish saying derives from Hokkien and translates to “What are you saying?”.

Rojak

Rojak is a common dish in Singapore, Indonesia and

Malaysia consisting of sliced fruits and vegetables served

in spicy palm-sugar dressing.

“Siapa nama mu?” translates from Malay literally as “who name you” and means “what is your name?”.

Adapted from a 2010 campaign to improve service sector hospitality in Singapore, words like “betterer”, “betterest” and “bestest” are improvements on the English word “best” that embody an impossible abstraction of being better than the best (Gwee, 2018).

“Apah sia ini?”, an Indonesian/Malaysian exclamation that translates to “What the [expletive] is this?” was the first thing that came to mind when I stepped into Queen Elizabeth Olympic Park. Whatever I saw in front of me was horrigible. I was blur like sotong, gabra like zebra, and ultimately, stunned like vegetable. The overwhelming majesty and staggering ineptitude of the visual phantasmagoria assaulting my every sensibility compelled me to learn more about this hulking monstrosity and write about the sociopolitical implications of its construction.

Siapa nama mu?

“Siapa nama mu?” translates from Malay literally as “who name you” and means “what is your name?”.

Best. Betterer, Bestest!

Adapted from a 2010 campaign to improve service sector hospitality in Singapore, words like “betterer”, “betterest” and “bestest” are improvements on the English word “best” that embody an impossible abstraction of being better than the best (Gwee, 2018).

Mampus

“Mampus” in Malay means “to die, to perish or to be

wiped out”. In Singlish, it is commonly used in a comical way to refer to oneself in a conundrum, or also as a

curse.“Apah sia ini?”, an Indonesian/Malaysian exclamation that translates to “What the [expletive] is this?” was the first thing that came to mind when I stepped into Queen Elizabeth Olympic Park. Whatever I saw in front of me was horrigible. I was blur like sotong, gabra like zebra, and ultimately, stunned like vegetable. The overwhelming majesty and staggering ineptitude of the visual phantasmagoria assaulting my every sensibility compelled me to learn more about this hulking monstrosity and write about the sociopolitical implications of its construction.

All illustrations and photographs by the author

Singlish?

I deploy Singlish as a mechanism to argue that a complex mix of disparate elements can be coherent, elegant

and pragmatic, unlike the elements of Queen Elizabeth

Olympic Park.Singlish, a portmanteau of the words “Singapore” and “English”, is an English-based creole language spoken primarily in Singapore, the entrepôt city-state in Southeast Asia that was once a British colony. The language contains combinations of vocabulary, turns-of-phrase and sentence structure from English, Mandarin, Malay, Tamil, Hokkien, Cantonese, Teochew, and Japanese, among other languages that are spoken by residents in the country. From my empirical understanding and academic research, Singlish is an elaboration of a pidgin language used between non-native English speakers as a means of communication in professional and social settings (Ong, 2017). The thread of pragmatism as well as commerce is as ingrained in the psyche of Singaporeans as it is in Singlish. Various ethnic groups were brought into the country by the British to serve various economic roles and to maintain social division and control (Chua, 2003). While most residents of the country are multilingual, Singlish serves as the de facto lingua franca.

Singlish syntax is consequently optimised for efficiency. For instance, instead of saying, “Why is it like that?”, Singlish speakers boil sentences to their essential elements, conjoin prepositions with adjacent pronouns, and inject emotion to form elegant syntactic structures: “Why liddat?” (Gwee, 2018).

End particles in Singlish are also immensely powerful and convey considerable meaning and emotion with minimal effort. Take the following set of expressions that convey increasing levels of frustration at a tricky situation.

“How leh?” — [curt, inquisitive, pleading] an earnest, curious ask for direction

“How ah?” — [medium, curious, slight annoyance] slightly frustrated plea for help

“How?” — [long, pleading voice] conveys an earnest plea for help in an unfortunate situation

“How sial?!” — [said like an expletive, sometimes with an ironic laugh] conveys intense frustration in a desperate plea to save an irrevocably bad situation

“How can?” — [desperate, said with intensity in each word] “How can this be allowed?”

Unlike Olympic Park, Singlish combines a gamut of influences to form elegant expressions of efficiency and pragmatism. Malu!

Powderful

Quotidian understandings of language as being synonymous with communication often follow from American psychologist B. F. Skinner’s behaviourist model of language acquisition. Skinner argues that environmental circumstances reward (for instance via parental approval) or punish (for instance via incomprehension) particular “verbal behaviours” to reinforce some expressions of language over others (Skinner, 1957).

However, the “father of modern linguistics” Noam Chomsky argues that there is in fact a “poverty of stimulus” that indicates children acquire language primarily through the development of a biologically innate structure as determined by the genetic endowment that all humans possess.

In fact, Chomsky asserts that communication is at best a secondary or tertiary function of language and that language is primarily an architecture of thought that develops from infancy to adolescence as a cognitive organelle (Chomsky, 1965).

It is with this idea of a biologically innate “universal grammar” architecture in mind (Chomsky, 2017) that I critically analyse Queen Elizabeth Olympic Park; its materiality is not only semantically nonsensical but syntactically unsound.

Chomsky in Syntactic Structures (1957) builds upon the transformative generative grammar model developed by his tutor Zellig Harris, an influential American linguist (Seuren, 1998). Chomsky composed the sentence “colourless green ideas sleep furiously”, which has no discernible meaning yet is a grammatically well-formed sentence of the English language to argue that syntax and semantics are independent of one another.

Language as an architecture of thought need not be expressed in written language. Well composed works of visual art including architecture can also be analysed with Chomsky’s conception of semantics and syntax.

Just as Chomsky’s “universal grammar” underpins all languages, a “universal visual grammar” can be deployed to argue that some visual representations are semantically or syntactically nonsensical.

Gong simi?

I deploy language as metaphor to analyse the structure of Queen Elizabeth Olympic Park, making the argument that the park as it stands today is rojak, or a structural and semantic mess that can be compared to Chomsky’s nonsense sentence: “furiously sleep ideas green colourless”.

Drawing from Emerald Necklace, Boston

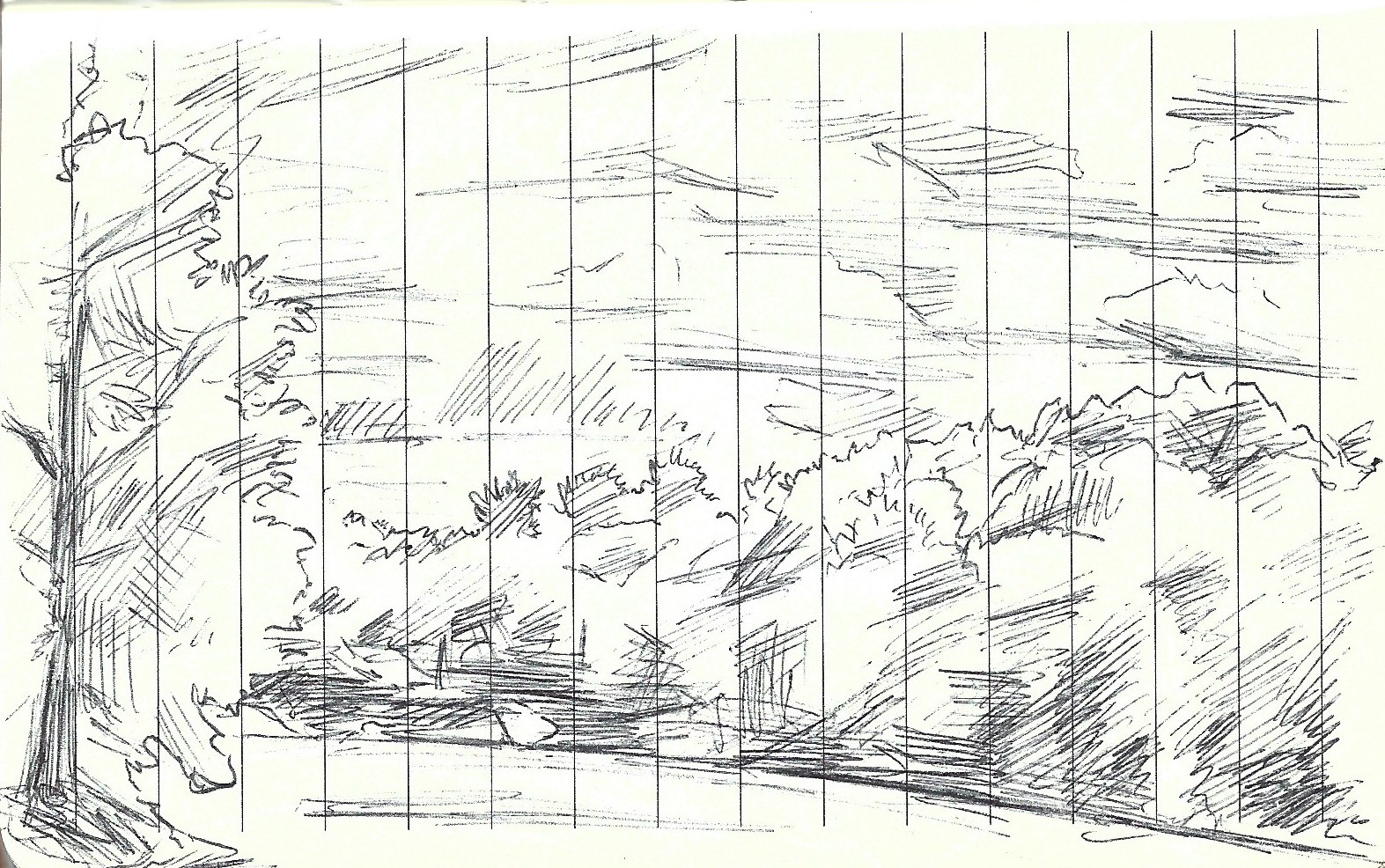

The influence of landscape painting typology on Olmsted’s work is strong.

The influence of landscape painting typology on Olmsted’s work is strong.

Siapa nama mu?

The architecture critic Rowan Moore writes for The Guardian newspaper that the south of Olympic Park is the “visual equivalent of several mobile ringtones going off at once”.

Who is the “park” in Queen Elizabeth Olympic Park? Is Olympic Park not “the biggest new park in Europe for 150 years” as promised by the UK government? (Department for Culture, Media and Sport, 2007)

The word “Park” in the context of Olympic Park is somewhat obfuscatory and should be seen as akin to the word “park” in “industrial park”, “tech park” or “retail park”, not parks in the context of landscape design.

Landscape Architecture in large part is influenced by the fine arts, in particular landscape painting. The landscape architect for Manhattan’s Central Park and widely considered to be the founder of the discipline is Frederick Law Olmsted. In Central Park and many of his other works, the idea of the sightline is integral. In fact, Olmsted designed several points and environments within Central Park in allusion to traditions of landscape painting. The intention is that park goers will step out of the hustle and bustle of the city into a virtual replica of a landscape painting (Schama, 1995).

The Austrian philosopher Ludwig Wittgenstein argues in Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus (1922) that language, or thought expression has limits and “what lies on the other side of the limit will be simply nonsense”.

I argue that the material realities of Queen Elizabeth Olympic Park are nonsensical when considered in the syntactical canon of the western landscape.

To borrow a concept from Wittgenstein’s later work, Philosophical Investigations (1953/2009), I argue that Queen Elizabeth Olympic Park bears a greater “family resemblance” to commercial enterprises like industrial parks.

Green promenades that bisect roads in Paris deploy a classic tenet of landscape architecture proportionality to make the space accommodating to pedestrians: tall trees that soften the transition between the pedestrian level and buildings on the other side of the road, followed by people-height shrubbery to soften traffic noise and to enhance the sightline, finally herbaceous plants at ground level as joinery between shrubs and the footpath.

I took a pilgrimage to Liverpool’s Birkenhead Park, widely considered to be the first civic park in the world funded by public monies. It is a public park designed by the English architect Joseph Paxton who later inspired Olmsted in his design of Central Park. What strikes me is that the industrial parks surrounding Birkenhead Park bear a greater resemblance to Olympic Park than Birkenhead Park itself.

The imperatives of a work of landscape architecture like Birkenhead Park are primarily civic: the design of the landscape architect intentionally generates a social and epidemiological good for the community.

The imperatives of industrial parks are more mercenary and certainly do not prioritise the experience of the park-goer.

Wittgenstein (1953/2009) argues that some concepts previously considered to be connected by a common essential feature can be better described as having a series of “ family resemblances” or a set of overlapping similarities with other objects of the same group. The paradigmatic example is the concept of a “game”. The argument is that there is not one essential feature that underpins all games but a series of similarities that link games, like a family.

Take the example of Football, Chess and Ring a Ring o’ Roses. All these are games but they do not have a common essential feature that coheres them as such. Instead, family resemblances like “both Football and Chess have clear rules and a winning objective”, or “both Football and Ring a Ring o’ Roses are social activities that can be enjoyable” cohere one game to the next like a family tree.

Following Wittgenstein’s framework of family resemblance, Olympic Park adheres more to the typology of a commercial park than to a civic work of landscape design.

My heartrate noticeably rises and I feel cortisol running through my veins as I step into Olympic Park. Scenes like the one depicted in this photograph illustrate the park’s semantic and syntactic vacuity.

There is a complete disregard for the proportional relationship between elements and the juxtaposition of forms can only be described as a relentless assault on the visual and emotional palate.

Best. Betterer, Bestest!

Comparing Queen Elizabeth Olympic Park with other large-scale works of landscape architecture within urban contexts helps to elucidate its failure to accomplish the explicit goals of its conception.

For instance, Olmsted’s Emerald Necklace in Boston, Massachusetts weaves the city together in a series of green walkways that link parks and gardens in a coherent and elegant form that provide immense social, ecological and practical function to the inhabitants of the city. Expanding parks like this into the urban fabric using techniques to improve biodiversity and access to ecological services is a much stronger approach to landscape design than developing a new region like Olympic Park.

Cities need to grow organically and with civic intent. Artificially imposing a new urban typology can seem like the best way to create a radical reimagining of the urban fabric, but the mercenary imperatives of big projects inevitably take over and consume the region in a grab-bag of floundering missteps.

Perhaps not surprisingly, the strongest instantiations of large-scale works of urban design happen in the context where state power supersedes all other imperatives (Waldheim, 2016).

The Chinese landscape architect Kongjian Yu and his firm Turenscape essentially designed a landscape plan for the entirety of China. Yu’s idea of “deep forms” and “sponge city” transformed swathes of urban landscapes in the country for the better, improving stormwater management to reduce floods, creating recreational space and helping improve the health of millions of inhabitants (Shannon, 2013).

While I find the authoritarian rule of law deplorable and repugnant, the overwhelming authority of the state allowed for a coherent and coordinated ecological transformation of an urban landscape that perhaps has no precedent.

Mampus

Queen Elizabeth Olympic Park is horrigible — semantically, syntactically and systematically unsound. It feels like the cauterisation of the decades long haemorrhage of British social democracy and represents the triumph of unaccountable private tyrannies over the built environment of London. I deploy Singlish in this review with the aim of demonstrating that pragmatism, efficiency and elegance can undergird a syntactic structure only through organic growth and experimentation, against the odds of imperial imposition.

This essay is reworked from a dissertation completed in 2022/23 for the Bartlett School of Architecture BSc Architectural and Interdisciplinary Studies ARIII Dissertation at University College London, supervised by Dr. Edwina Attlee.

Works Cited

Chomsky, Noam (1957), Syntactic Structures. The Hague: Mouton & Co.

Chomsky, Noam (1965), Cartesian Linguistics. New York: Cambridge University Press

Gwee, Li Sui (2018), Spiaking Singlish: A Companion to How Singaporeans Communicate. Singapore: Marshall Cavendish Editions

Schama, Simon (1995), Landscape and Memory, London: Harper Collins Publishers Seuren, Pieter A. M. (1998), Western Linguistics: An Historical Introduction. New Jersey: Wiley-Blackwell

Shannon, Kelly (2013), “(R)Evolutionary Ecological Infrastructures”, Designed Ecologies: The Landscape Architecture of Kongjian Yu, edited by William Saunders, Berlin, Boston: Birkhäuser, pp. 200-211

Waldheim, Charles (2016), Landscape as Urbanism: A General Theory, Princeton: Princeton University Press

Wittgenstein, Ludwig (1922), Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus. London: Kegan Paul, Trench, Trubner & Co., Ltd.

Wittgenstein, Ludwig (1953/2009) Philosophical Investigations, 4th edition, Oxford: Blackwell Birkenhead Park (1847), “The People’s Garden”, https://birkenhead-park.org.uk

Chomsky, Noam (2017), “The Galilean Challenge: Architecture and Evolution of Language”, Journal of Physics: Conference Series, 880 (1)

Chua, Beng Huat (2003), “Multiculturalism in Singapore: an instrument of social control”, Race and Class, Vol. 44(3), pp. 58-77

Moore, Rowan (2014), “Queen Elizabeth Olympic Park review – no medals for visual flair”, The Guardian, April 6, https://www.theguardian.com/uk-news/2014/apr/06/queen-elizabeth-olympic-park-reviewdisneyfied-new-york-high-line

Ong, Kenneth Keng Wee (2017), “Textese and Singlish in multiparty chats”, World Englishes, Volume 36, Issue 4., pp. 611-630

Wainwright, Oliver (2022), “‘A massive betrayal’: how London’s Olympic legacy was sold out”, The Guardian, June 30, https://www. theguardian.com/uk-news/2022/jun/30/a-massive-betrayal-how-londons-olympic-legacy-was-sold-out

Julæ Tan is contemplating the purchase of another book she’ll never read.