Written in Stone: Lineage, Legacy, and Letterforms

Irina V. Wang

MID 2020

Photographs by the author.

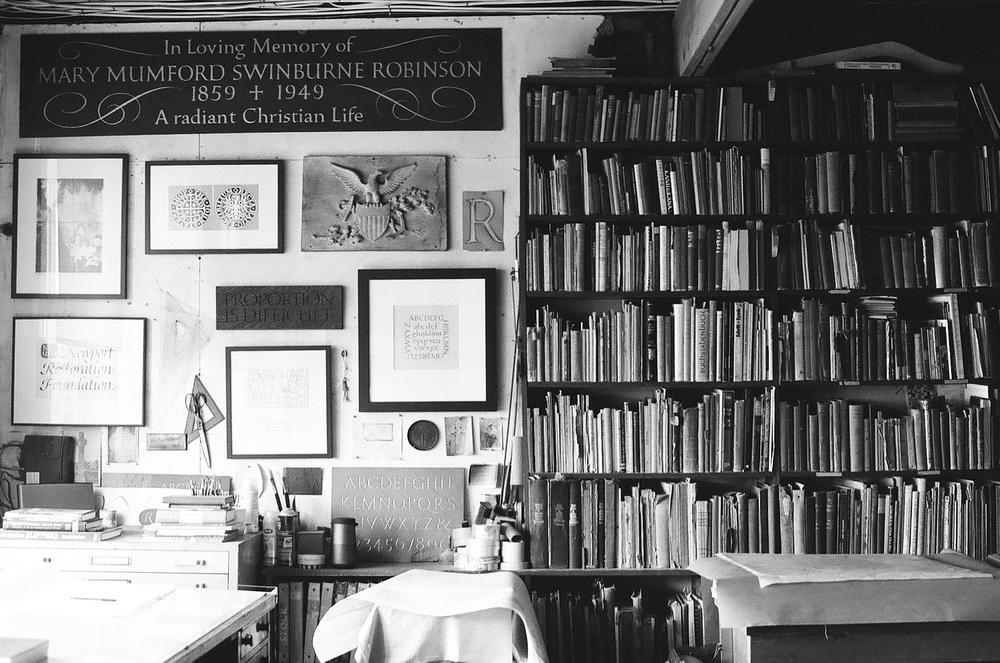

Photographs by the author.Stepping through the red door of the John Stevens Shop, I thanked the owner, Nick Benson, for letting me drop by on such short notice. He said it was no problem for him, but a shame for me considering the weather conditions. To the contrary, I had travelled grinning through the wall of white fog obscuring the bridge from Jamestown to Newport, thinking I can’t believe my luck. It was exactly the right weather for walking around an 18th-century New England burial ground.

Just up the road, the Common Burying Ground and Island Cemetery boast the largest concentration of colonial-era headstones in the country—many the handiwork of the John Stevens Shop, which has operated from the same spot for three centuries and is now run by Nick, a third-generation stone-carver.

The Bensons are a formidable family force, in both regional and national history. When John Howard Benson bought the business in 1927, it had already been at the forefront of New England monument trade tracing back to 1705 when mason John Stevens arrived from Yorkshire, England. Nearly a century later, the Bensons’ collective résumé includes carvings and inscriptions for the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the JFK Memorial at Arlington National Cemetery, the FDR Memorial, the Vietnam Memorial, the National Gallery of Art, and a handful of prestigious universities. Just within the last decade, Nick was awarded the MacArthur “Genius” Fellowship and commissioned to design and inscribe bespoke lettering for the Martin Luther King, Jr. Memorial on the National Mall.

Whether referring to the grandfather he never met or the father who raised him as a boy then trained him as a stone-carver, Nick speaks with an emphatic respect free of biased sentimentality—the sort of objective praise you’d have for a president or olympian. He seemed mildly bewildered when I asked whether a particular Benson engraving influenced his personal practice: “Oh there are many. Many, many, many that I consider to be masterpieces.”

When I pressed him to name a particular stone, he sighed with the reluctance of a lifelong bibliophile asked for their favorite book of all time. Still, risking reductiveness, he had an answer: In 1945, his grandfather carved a stone for the Jacoby family, which was situated in a small plot by St. Mary’s Episcopal Church, just up the road in Portsmouth. “What makes it such an incredible piece is that it’s very much a product of his artistic sensibilities, absolutely nothing to do with what was going on in the monument trade at that time,” Nick said. “He really took a left-hand turn; he basically made headstones that were pieces of sculpture.”

Once my expectations were primed by all this promise, seeing a photograph of the Jacoby stone on Nick’s computer screen was admittedly underwhelming. It was beautiful but terse, laid out stark and stoic on the slate like a modernist poster. Feeling sheepish about my reaction, I asked what it was like for him when he saw the stone for the first time. He thought for a while, and said, “I wouldn’t have understood it at that young an age, or even when I was beginning to work here. It takes about a decade for you to appreciate what happens with all of the subtleties involved with all of it, and then another decade or so to really dig into it. I went to Rome recently to research a whole bunch of inscriptions there, and it was like seeing them for the first time even though I’d been before.”

* * *

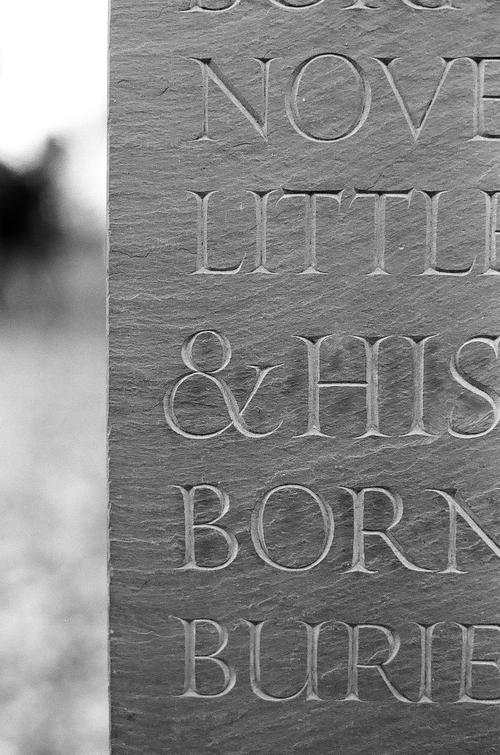

Armed with this permission, I visited St. Mary’s cemetery the following week in hopes of justifying my own ignorance. Instead, I found myself captivated: what seemed ascetic and stern in the photograph was elegant and stately in reality. John Benson’s chisel marks were evident in each groove, patterning the letterforms with striations like the marbling of the slate itself. In a plot full of lichen-covered sandstone shapes, the Jacoby stone stood surprisingly slim and perfectly rectangular, black-on-black disturbed only by a rusty tinge lining the tool marks. I circled it for over an hour, burning through two rolls of film—just as I’d decide to leave, a cloud would drift and the light would change in a way that had me greedily winding up my camera again.

By the time I made my way south for “beer-o’clock Friday” at the John Stevens Shop, the clouds had blown over altogether. Unlike that first foggy visit, it was golden hour in early April and the shop was awash with the barely-there warmth of Spring sunshine.

I was greeted by Nick and his father, a group of their friends, and a very happy dog. I felt surprisingly at ease amongst mostly middle-aged men, accomplished artisans with well-worn hands—and they seemed similarly unfazed by my presence. Sharing drinks at the end of a work week, everybody admired the balanced weight of a carving mallet, passed around an old panel of oak, and fondly remembered a particular piece of granite. I couldn’t help but feel a twinge of pride when they were taken aback by my analogue film camera, as if recognizing I was on their team.

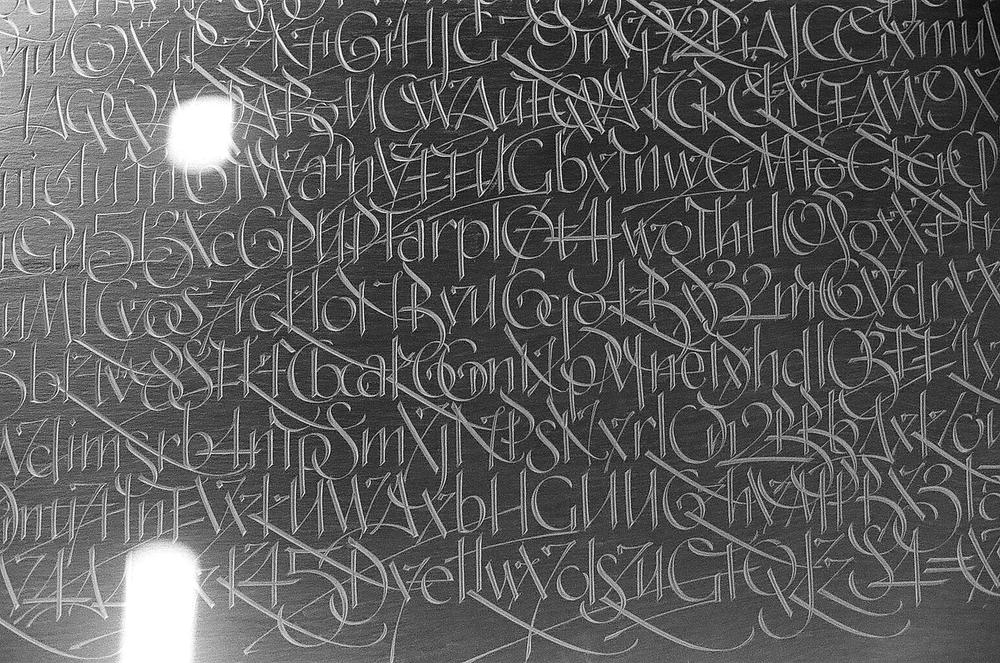

After all, the shop has been an analogue outpost for 300 years. When John Benson bought it from the Stevens, the industry as a whole was turning toward mechanized sandblasting. He steered it firmly towards designing and cutting inscriptions by hand, and it’s this commitment to craft production and the Roman capital that defines and distinguishes the Bensons’ practice today. In the modern-day interpretations of traditions he’s inherited, Nick cuts calligraphic flourishes into granite as if it were nib on smooth parchment. He still works on grave markers and monuments, but the stone has also become a medium for his own commentary. On one wall of the shop is a slate covered in elegant typographic knots: his tongue-in-cheek transcription of digital gibberish, a PGP email encryption key.

“It’s the evolution of computer technologies and how they’re applied to the monument trade and inscription work that I find difficult,” Nick says. “If you can hook up a diamond milling machine to a CNC CAD system and pump out some sort of three-dimensional carved version of something-or-another, people are enamored with the process, but the product itself is pretty pale. It has nothing to do with the human touch.” He adds, “And you know, we are human. We respond to that on subconscious levels that people don’t even realize. I ended up taking my own left-hand turn by making artwork now that’s in contemplation of all that.”

* * *

Nick’s dilemma is also on my mind, and thick in the air at RISD. Students, faculty, and administration alike are grappling with ways to hone time-honored craft while remaining relevant in an age of rapid technological change. The problem is linked to our individual practices and our departmental methods; it’s then magnified by the inheritance of RISD’s institutional legacy, by learning and practicing within a school founded upon values of craftsmanship and—for better or worse—often preceded by the reputation of that legacy. Even the Benson story is enmeshed with the RISD story: John Howard Benson was a professor here from 1931–1956 and designed the original diploma and seal; Nick’s father, Fud, studied in the Sculpture department; Nick’s brother, Christopher, graduated from Painting. How do we—all of us—acknowledge, integrate, and ride the waves of technological succession without sacrificing the traditions of institutional and familial succession?

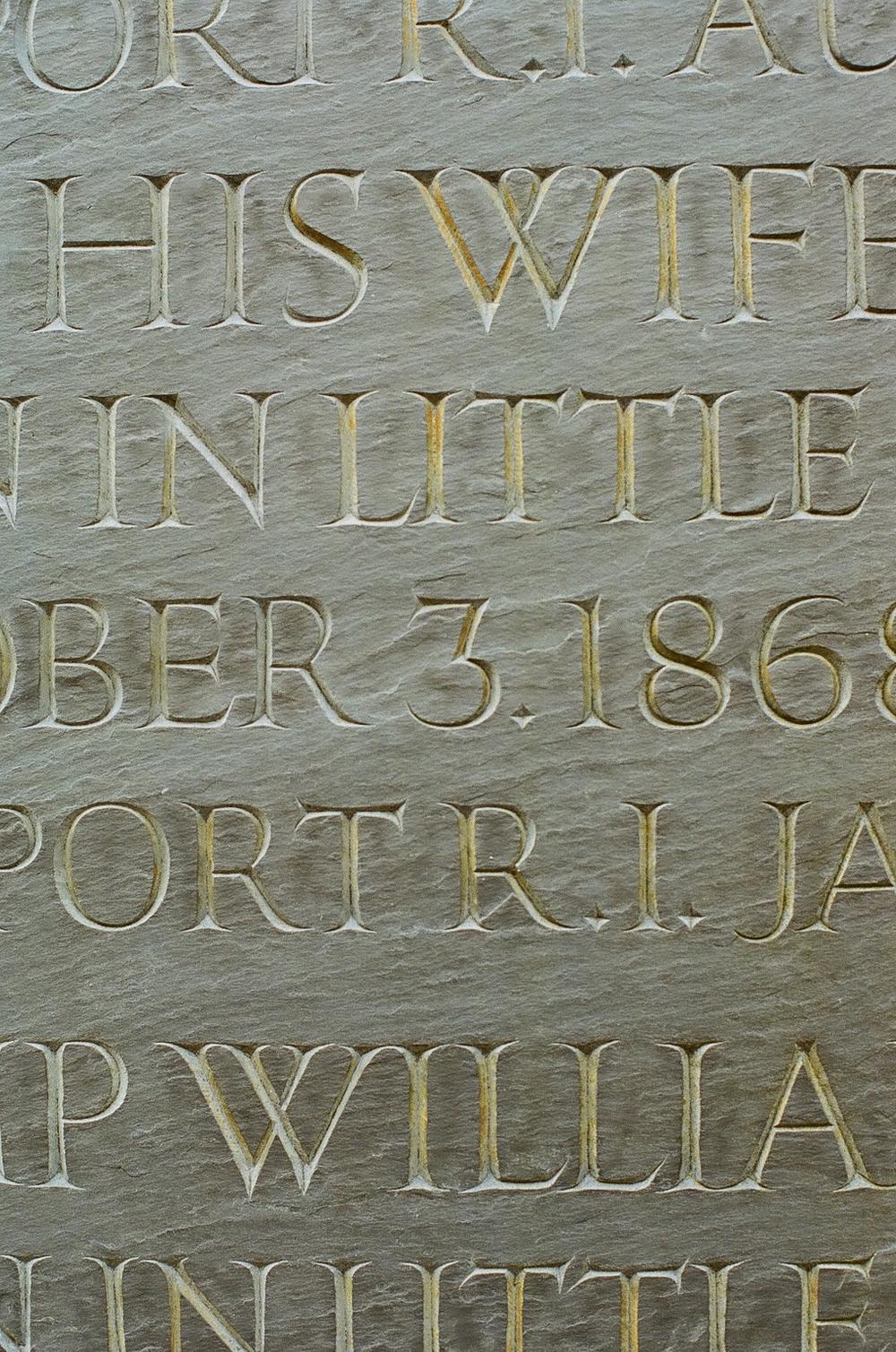

The question brings to mind another work-in-progress Nick showed me: an A-to-Z alphabet stone for the Houghton Library at Harvard. The collection’s founder, Philip Hofer, commissioned one from Nick’s grandfather in the 1930s, and later from Nick’s father; now Nick is adding his own alphabet family into the family of alphabets. During my last visit, he was painting the letters directly onto stone with a white-dipped brush in preparation for hammer and chisel—the ancient Roman way, his grandfather’s way, his father’s way, his own way.

And so, generation after generation, the Benson legacy in the monument trade is exercised through the act of chiselling others’ legacies into stone. When the most recent member of the Jacoby family passed away, it was Nick’s inherited duty to add an inscription onto the near-sacred stone that set a precedent for his personal practice. He laughed nervously, even as he recalled it to me now: “It was a little daunting because I’m not [my grandfather]. I did my best to make it look like him, but it was tricky and I felt like it was slightly sacrilegious, you know?”

I tried to smile reassuringly; I do know, in a roundabout way. My own grandfather was a renowned Chinese calligrapher practicing in Taiwan, where his craft is among the most respected of ancient traditions. In an otherwise artistically dry genetic landscape, our family always attributes my creative inclinations solely to him. Putting my own spin on this inheritance was inevitable, given that my grandfather and I were separated by generations, language barriers, a big ocean, and an even bigger culture gap. But I often imagine a parallel reality where he had trained my father who then trained me, where I might have grown up studying the complexities of pictographic language evolution across millennia and the lyricism of Classical Chinese poetry revealed by brushstroke.

In reality, I somehow gravitated towards letterforms, literature, and linguistics even without that seamless legacy. I wonder what proportion of nature and nurture was at play when I unearthed my love of typography through European graphic design.

Was it pre-written that my practice take a turn from book design to endangered language preservation? Am I straying too far, now that I’m drawn to the design of objects and the systems they exist within? My investigation into tombstones began as a fascination with mourning memorabilia; in the end, I’d arrived back at a hand-painted alphabet. My father, no artistic bone in his body, is a field scientist with a PhD in Geology. Is it a stretch to consider his lifelong fascination with rocks an iteration instead of a discontinuation? Maybe that was his own “left-hand turn,” a deep dive into the material substrate that bore all the ancient inscriptions his father chose to interpret calligraphically.

Legacy casts long and shifting shadows, even for the glyphs themselves. Modern Chinese calligraphy traces back to ancient Seal Script characters standardized during the Qin dynasty in 221 BCE. The most elemental part of Nick’s inscription work—the classical Roman capital—has been the foundation of our Western typographic landscape since Trajan’s Column was completed in 113 AD. Paul Shaw’s description of it in The Eternal Letter sounds to me like the double-bind of family legacy: “It is either an exemplary model to be extolled, worshipped, and replicated or it is an overhyped specimen to be adamantly avoided.”

Nick has mastered a third strategy of inherit-and-innovate—revering and meeting the standards set before him, but bypassing the pressure of direct comparison by pioneering a distinct style and theme within the craft. That’s just what his grandfather and father famously did before him, creating work that was so artistically distinct that it carried the industry forward to new realms; in compensating for the complications of legacy, they built upon and enriched that same legacy.

Could the same ever be said of a lineage punctuated by the distance of time, language, oceans, culture? When I hold my grandfather’s heavy jade seals or see his scrolls hanging on a stark museum wall, there’s a sense of profound knowledge-loss. When I’m magnetically drawn to his old books of poetry and leaf through pages without comprehending their contents, I imagine the parallel reality of direct inheritance, the one Nick gets to live out with all its challenges and rewards. Legacy is something solid and grounding, foundational even when its weight becomes limiting or paralyzing. But maybe distance distinguishes another model—one that acts less like an anchor, more like a beacon. I know a legacy that guides even as it remains shrouded in hazy mystery. I am not secured to it, only drawn toward it. Along the way, it grants permission in inheritance, promises thrilling freedom in iteration.

Irina Wang is still working out how to spin nuclear waste management as the current iteration.