Addressing the Empty Plinth: Lessons from Gallery Shows and Public Art

Jeremy Wolin

→ BIA 2019

Illustration by the author.

Illustration by the author.

This past September, a retrospective of the work of British sculptor Rachel Whiteread opened at the National Gallery of Art in Washington, DC. Whiteread is well-known for casting the negative spaces created by objects as small as a toilet paper tube and as large as a house, pushing the boundaries of the medium in the process. The show winds through Whiteread’s work chronologically, starting with her earliest explorations of space and highlighting her most high-profile sculptures, including Ghost (1990), a plaster cast of a North London parlor, and House (1993), the temporary concrete vestige of a demolished East London terrace house.

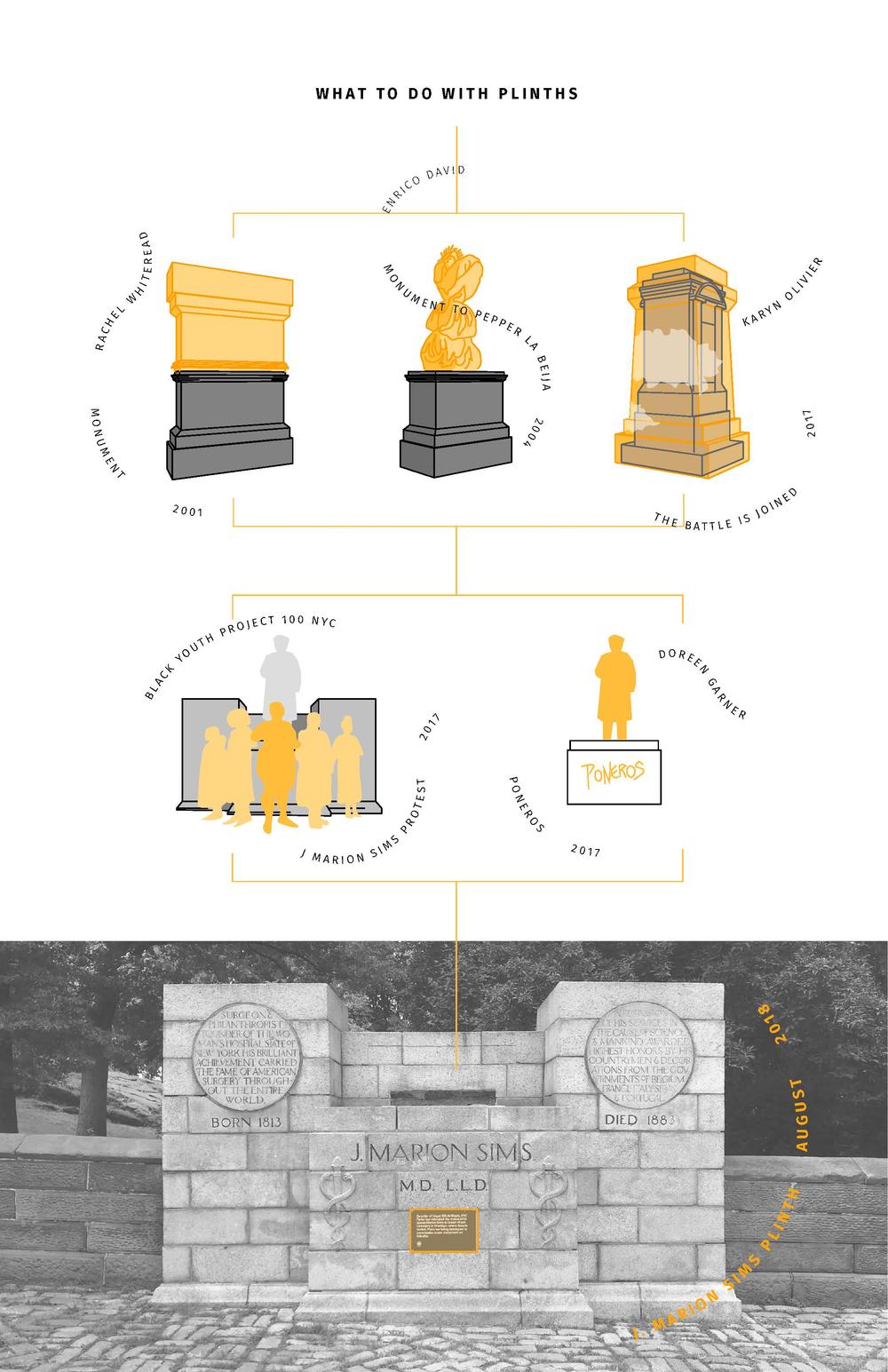

At the show’s end sits a maquette, about three feet tall, of Whiteread’s Monument(2001), the third installment of the Royal Society of Arts’ Fourth Plinth Project. The project began in 1998 as an effort to temporarily inhabit the lone empty plinth in London’s Trafalgar Square, a pedestal left open since its construction in 1841 due to a combination of insufficient funds and controversy over whom to memorialize at that location. Whiteread’s two predecessors, Mark Wallinger and Bill Woodrow, each alluded to social themes in their works, but both fell back on the male figure or bust as a means of symbolizing humanity. Whiteread’s intervention signified new territory. Visible in the show’s documentation images and in the maquette itself, her gesture inverted the base in both form and materiality, recreating a replica of the solid plinth in cast resin and placing it upside-down on the original to create a mirror image.

The removal of Confederate monuments throughout the United States, increasingly frequent since the Charleston church shooting and Charlottesville Unite the Right rally, has provided many municipalities with empty plinths like that of Trafalgar Square. Under an hour’s drive from the National Gallery, the city of Baltimore, Maryland, removed four statues in summer 2017, leaving four open platforms. Earlier that year, New Orleans officials removed three monuments amid protest, resulting in similarly unresolved plinths. This past August, students in Chapel Hill, North Carolina, pulled down a Confederate soldier themselves, one year after activists in neighboring Durham toppled that city’s statue.

Whiteread’s Monument is not alone in alluding to the diverse potentials of these newly empty spaces. By 2001 and even much earlier, the plinth already stood as a relic of an earlier era. Modernists, like Constantin Brancusi, subsumed it into their sculpture, Minimalists discarded it in favor of a more direct relationship between the viewer and the work. With Maya Lin’s Vietnam Veterans Memorial, the plinth became old-fashioned in more populist monumentation as well. Yet plinths remain in the built environment, supporting monuments that long outlive their makers. Instead of decisively answering the question of what to do with the space atop this outdated object, Whiteread forgoes the statue and materializes the absence in its place.

Though undoubtedly the photos and maquette of Monument do not compare to experiencing the work in person, their presence in the National Gallery alludes to the roles of documentation and proposal materials in exposing such works to a wider public. Artist sketches and renderings often lack the awe of built works, but have the power to distort the image to create highly curated messages about the artist’s intent. The space of the proposal also allows for the communication of works too impractical, too expensive, or too provocative to build in full physical form. This, in a way, makes the proposal a more democratic monument.

Several years after Whiteread’s installation, the CCA Wattis Institute of Contemporary Art in San Francisco mounted the exhibition Monuments for the USA. A collection of proposals for new monuments, the show included more than sixty artists from the US and abroad. A replica of Trafalgar Square’s empty plinth appeared in Italian-British artist Enrico David’s contribution to the show, Monument to Pepper LaBeija. Working across mediums, David often produces figures distorted into shapes that verge on the sinister or uncomfortable. In this work, David takes the monumental vocabulary of a statue atop a plinth and replaces the white heterosexual man with an African American drag queen in a gold lamé gown. LaBeija, of the Harlem drag ball House of LaBeija, was immortalized for a wider public by Jennie Livingston’s 1991 documentary Paris is Burning. In David’s rendering, she stands out against a backdrop of Lever House, a building located where Midtown East meets the Upper East Side and which symbolizes a certain New York elite. Miles from where the the House of LaBeija operated, David’s placement of LaBeija against this backdrop signifies a transplantation of Black queer culture into the center of wealthy, white New York. Rather than remove the sculptural base altogether, David reclaims it, siting a figure of his own admiration in its place of public honor.

A decade later, as part of the Philadelphia Mural Arts Program’s Monument Lab, Philadelphia-based artist Karyn Olivier proposed another answer to the question of plinths. In The Battle Is Joined, Olivier wraps the city’s Battle of Germantown monument in mirrored acrylic, creating a reflective surface. Here, Olivier reverses the viewer’s gaze toward the solid stone with a view outward. In its existing state, the monument had become easily ignored, no longer representative of the collective memory of the neighborhood’s new communities. With Olivier’s mirrors applied, the plinth reflects the neighborhood around it. The material also makes the plinth disappear slightly at a distance, only revealing its scale when viewers are close enough to see themselves in the monument’s skin.

While Olivier constructed the mirrored shell that encased the Battle of Germantown monument in summer 2017, Black Youth Project 100 was protesting New York’s J. Marion Sims Monument. Sims was a well-known surgeon in the 1800s, known as the “father of modern gynecology.” Referencing Sims’s inhumane practice of performing experimental surgeries on enslaved women without anesthesia, four activists donned medical gowns and splashed themselves in red dye while chanting “Fuck white supremacy.” Their protests lent a visual display of anger toward the monument and the memory it carried, contributing to a long history of protest at its site.

Black Youth Project 100’s creative activation of the Sims monument serves as a counterpoint to Olivier and Whiteread in forgoing institutional support when working in public space. All three, however, complicate the idea of public space as more accessible than a gallery or museum setting. Each entailed the navigation of complex bureaucracies and laws governing public assembly that required varying levels of temporality for each activation. This limited the lifespan of Olivier and Whiteread’s works to months; for BYP100, minutes. After de-installation, each lives on through documentation, not unlike David’s first rendering of Pepper LaBeija, relying on photographs, video, and personal retellings to persist for what artist and writer Suzanne Lacy calls “the audience of myth and memory.”

Eight months after BYP100’s protest, the statue of Sims was removed from its plinth and relocated to Greenwood Cemetery in Brooklyn, the lone casualty arising out of the Mayoral Advisory Commission that formed in fall 2017 to evaluate New York’s monuments (its purview included statues to Christopher Columbus and Teddy Roosevelt as well). Throughout summer 2018, the plinth stood on Fifth Avenue at 103rd Street, devoid of its figure but still bearing his name and accomplishments etched into the stone face. A solitary plaque tells of Sims’s removal and alludes to the creation of a new sculpture in its place, but erases the history of protest at the site. In its emptiness, the plinth speaks volumes. In its presence, it remains a question left unanswered.

Jeremy Wolin is in his fifth year of the Brown-RISD Dual Degree Program and is writing a thesis in American Studies on exhibitions of artist-made monuments.