A Vagabond Viking Voyage and Midsummer Daydream

Mike Fink

→ Professor, Literary Arts & Studies

Photographs by Irina V. Wang

→ MID 2020

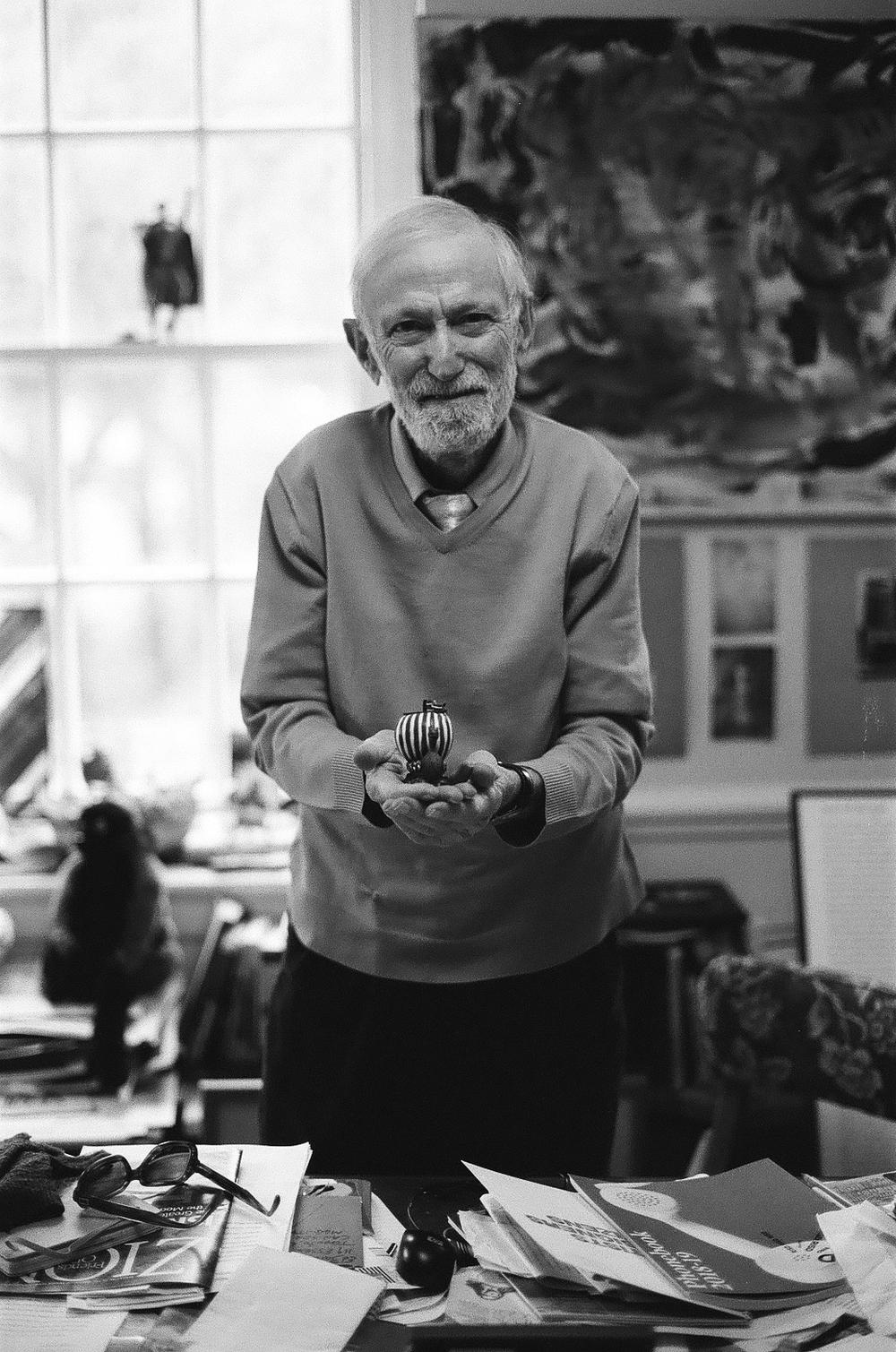

Mike Fink holds a Viking statuette, a souvenir from his Scandinavian pilgrimage.

Mike Fink holds a Viking statuette, a souvenir from his Scandinavian pilgrimage.I’d been planning this project for many a season—a poetic pilgrimage to Stockholm to visit the graves of two Scandinavian heroic figures who died but left no legacy in ash or bone or even progeny. Only in truth, myth, and monument. One, Raoul Wallenberg, the architect and humanitarian who inspired statues, memorials, books, and movies with his noble, nearly inexplicable heroism as a rescuer of the doomed. And another, Greta Garbo, the film star known for her obstinate rejection of any invasion of her privacy. Shy as she was, she conceived a plan to visit Hitler, her esthetic admirer, with a pistol hidden in her bodice to shoot him dead and thus save the world.

I grew up during the tragic eras of the Depression and then the Duration (of World War II). If I were not here in the land of Roger Williams, I would most likely have been murdered by the Nazis, or perhaps hidden by kind strangers among those who joined the Resistance instead of the Collaboration. I had witnessed the unemployment: on our block and beyond, and my generation grew used to wanderers knocking on the door seeking a cup of soup or lodging for the evening. The world was at war one way and another, and my cousins and uncles left these shores to fight the battles for the Four Freedoms (from want and fear, of free speech and religion). Among my classmates, there were some hidden Jewish refugees or survivor children. I did not suffer directly from these major events. I did, however, derive my values from events of such magnitude. The Depression taught thrift and a kind of humility, the Duration offered lessons in sacrifice, tragedy, and courage. These were my anchors—like the flag of Rhode Island and the first RISD logo.

As a boy I was always labelled a “contrarian” by classmates, cousins, and even my mother. Whatever others thought, said, wrote, I would go against. If a movie was a cash success and won prizes for its popularity, I would pan it with a sneer. On the other hand, if it lost out with the audiences, and I might find myself alone in the theater, I could find beauty, depth, and wit somewhere among the credits, the details of the design. Recently, a colleague used the term “recalcitrance” to describe a quality of stubborn resistance unique to the Swedes and their neighbors in Norseland, in the vicinity of Viking lore. I like this variation on “contrarian.” The ultimate value of “recalcitrance” is as an antidote to the bandwagon of rage and disdain that dominates our civilization, the loud opinions and mass movements instead of solitary “existential” searches. This is the quality I saw in Wallenberg and Garbo, and sought on my pilgrimage to Scandinavia.

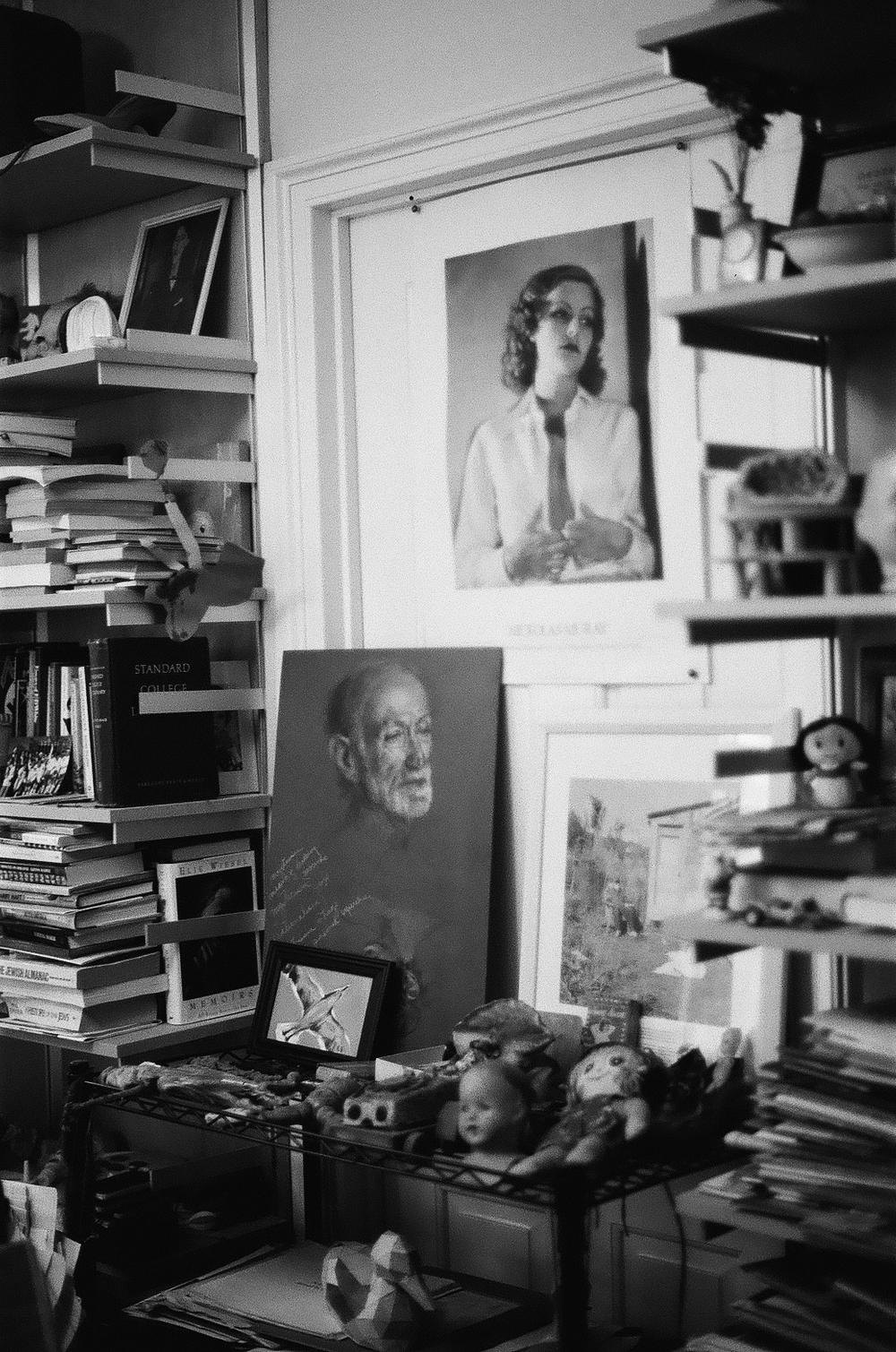

A poster of Greta Garbo on the wall of Mike Fink’s office in College Building.

A poster of Greta Garbo on the wall of Mike Fink’s office in College Building.Wallenberg studied architecture here in the US but returned to his wealthy and aristocratic clan in Sweden, which had taken a neutral stance in the Nazi era. On board the ship home, he saw and was inspired by Pimpernel Smith, the movie with Leslie Howard about a shy professor who secretly saves the Jews and helps the Resistance. Arriving safe and secure at home, Wallenberg asked his mother to pack a trunk with fine champagnes, cognac, and his fanciest wardrobe. He “set up shop” in Budapest and hosted an elegant dinner for the Nazi official Adolf Eichmann himself, warning the villain that he would lose the war and be hanged for his crimes against humanity. Wallenberg then boldly proceeded to sign papers claiming the refugees on the cattle cars bound for murder and horror in Auschwitz were legal Swedish subjects. Under the guise of this feigned arrogance and brazen style, he rescued ... how many? I dare not say, but a significant number. At war’s close, Wallenberg was arrested, but not by the Germans. The Russians assumed he was an American spy, and thus he died in a gulag after many years of solitary confinement.

I had already visited the sculpture of Wallenberg in Budapest, as well as the memorials in Washington D.C. and New York City. Several semesters ago, I came upon one Nicholas Wallenberg at the end of my alphabetical class list. Reading it aloud, I asked him, more playful than serious, if he was maybe a distant cousin or relation? His answer astounded me: “Yes, I am his great nephew.” I invited him home to dinner and took him across the street to meet a woman whose family had been saved by his great uncle. Believe me, there were hugs and tears aplenty at this rendezvous with destiny. And now here I was at the major park in Stockholm harbor where a large stone globe is inscribed with Wallenberg’s name and an account of his life and death. It took me two days to find this sacred space. A historic royal figure dominates the grand garden—a kingly military man on horseback—and I could not find the relatively modest corner dedicated to Wallenberg until my second attempt. I lost a day in my quest. I tried again the next morning. I persisted with recalcitrance.

In contrast to Wallenberg, Greta Garbo chose cremation. Her remains were to be scattered anonymously, to avoid indiscreet intrusions. So I had to be satisfied with her headstone and its calligraphy. She never signed autographs for the public except here, in a way, in a beautiful Stockholm cemetery with flowers and trees and a gracious approach of flagstones.

Garbo spoke no English at the start of her career, but the expressiveness of her face and features in close-up captivated the movie-going public. I have shelves of books about her films, her rather lonely life, her resistance to fame and its attendant publicity. She walked out and away from Hollywood, but left behind magnificent images, gestures, and memorable words once the talkies shook up the silent industry. Perhaps the most prophetic, and poetic, of her performances was as Queen Christina, who abdicated her throne and homeland in search of an impossible “happiness.” Recalcitrance? In Ninotchka she abandons her role in the Russian revolution. In Anna Karenina she rejects life itself in her rebellion against the respectability of a loveless marriage. She brought artistry, tragedy, and mystery to the screen. The three Great Beauties—Garbo, Dietrich, and Lamarr—united in their contempt for Nazi Europe and their respect for America when our culture stood for the Four Freedoms.

Homeward bound, there was a stop at the Jewish Museum in Copenhagen’s Royal Garden, where architect Daniel Libeskind tells the tale of courageous and determined fishermen who rescued the Jews of Copenhagen, shepherding them to safety in the neutral neighboring country of Sweden. It was here in this very small chamber with tilted walls, crooked floor tiles, and alcoves filled with mementos of Jewish history, that I found myself shaking with sobs. What moved me about Denmark during the War was the contrast between the humble heroism of the rescuers, the profound gratitude of the saved, and on the other hand the enormity of those who were not rescued and the recognition of the vastness of indifference toward the suffering of others that marked the era. It haunts me to this day.

During the pilgrimage, my thoughtful wife purchased a Viking statuette to add to the crazy shelves in my RISD office. So now that I am back home among the junk mail and old newspapers, I can look backward, sift and sort, and come to a sigh of satisfaction that I have indeed paid homage to my hero and my heroine and everything that inspired them. Thus: Wallenberg and Garbo; Depression and Duration; highs and lows; glimpses of greatness and the disappointments of the actual. Is there a “moral” to this travelogue? You decide: don’t join the crowd, consult your own soul!

Mike Fink welcomes visitors to his chamber, and will explain whatever amongst the threescore and more clutter interests his guest!