Negative Space

Mays Albaik

→MFA Glass 2019

I sang a lot as a child.

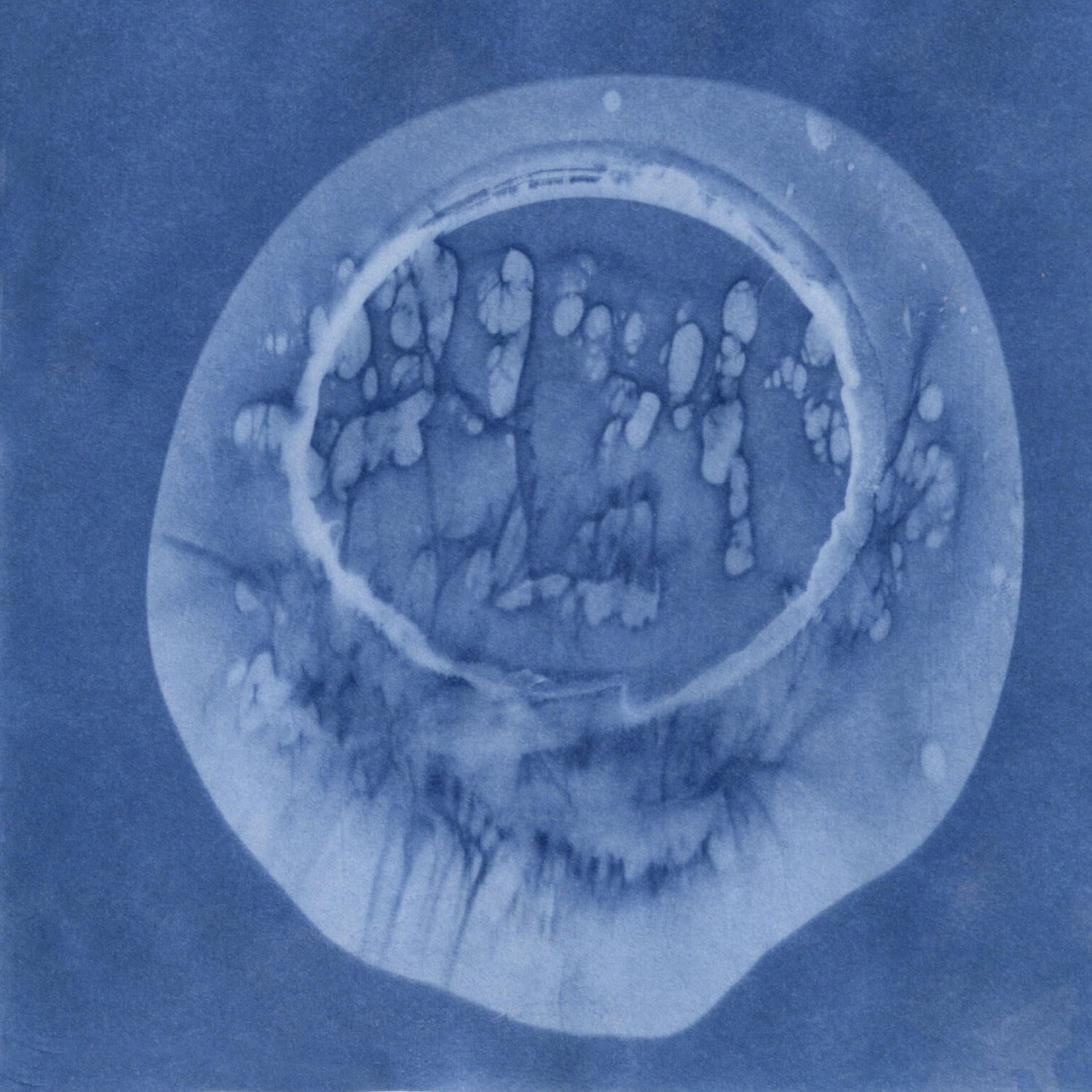

![]() This and all images below: Mays Albaik, from the series "Recordings, Translated," 2017, cyanotype prints

This and all images below: Mays Albaik, from the series "Recordings, Translated," 2017, cyanotype prints

While celebrated for its natural history collection and earthy character I had a throaty voice, and adults found it beautiful. My lungs caught bronchitis often, and the coughing scratched my throat.

The older I grew, the less sick I got, and the cleaner my voice became.

It wasn’t the same with my mouth.

The older I grew, the filthier it got, as though the phlegm that chafed my chords didn’t disappear, but instead became curses, and moved closer to my lips. Closer to the outside world.

This dirtiness sat, behind my teeth, under my tongue, for years.

It festered, and as an adolescent, I had many ulcers. I had pristine school reports, and my teeth were pearly white. But something in my stomach was pushing at my mouth. The skin broke open and my mouth bled, but my words stayed inside.

Then they slowly trickled out. They leaked between my teeth, through my parted lips, first in breaths, then whispers, then in words, and finally hacking coughs. My chest came full circle.

![]() I think, sometimes, that my body formed around my mouth.

I think, sometimes, that my body formed around my mouth.

With every cough a secret tried to escape. The belt of three stars, sea-salt drying on the shore, the taste of waves lapping against stones. My secrets, saffron kisses like warm winter tea, and words whispered like thin summer clouds.

But they were inside, pressed together, calcifying, not clouds anymore but slow rock, odorless in their immobility. In their imprisonment, tasteless.

Around them, my tongue morphed. My teeth, the teeth I ground to keep the clouds in, bled, then broke, then, around their debris, regrew anew. My lips flayed, then regenerated, and now they sit, my words’ sore and swollen gate to the world.

![]() I think bodies form around their negative spaces.

I think bodies form around their negative spaces.

Looking for someone else’s secrets, I found fossils in my ears. They looked like words, but ones I’d never heard before. They had been sitting for years, hardening, settling. The brackets that held my thoughts from tumbling, from the clouds.

I put the words back in, but my ears hadn’t stopped forming, deforming, reforming. The brackets were loose, the secrets ill-fitting, and the headaches started.

![]() I think the words inside my body are the hammer to the anvil of the world outside.

I think the words inside my body are the hammer to the anvil of the world outside.

I ignored the headaches. I was sure the problem was in the back of my neck. My skin crawled at the smell of saffron, the taste of sea salt. Every morning I’d wake to summer clouds, and my hackles would rise. Every night I’d sleep beneath three stars.

It had to be my dreams. They drained out like septic water every morning, clotting my hair, soiling my pillows. They never fit around my neck, until I redrew my head, re-stretched my spine, replaced my skin.

I slept better then, but I still ached. The sea salt was in my lungs, the sun’s fire in my gullet. I thought of bronchitis, like it were an old friend, and of words like “rock” and lungfuls of stones.

![]() I think the spaces of my body work in tandem to stop it from being.

I think the spaces of my body work in tandem to stop it from being.

I had been breathing smoke all my life.

Never a smoker when everyone else was (even the stars on moonless nights), I inhaled their tobacco breath and never breathed it out. It stayed in, pushed at itself. It coalesced, churning, flashing, a dense thundercloud of ever-changing unattainabilities.

Then I decided to sing again.

I sang in front of a mirror, “Watch your chin, your shoulders,” my instructor would say. But I watched my ears as they bled, my chest as it heaved. I watched the smoke leave my body.

This and all images below: Mays Albaik, from the series "Recordings, Translated," 2017, cyanotype prints

This and all images below: Mays Albaik, from the series "Recordings, Translated," 2017, cyanotype printsWhile celebrated for its natural history collection and earthy character I had a throaty voice, and adults found it beautiful. My lungs caught bronchitis often, and the coughing scratched my throat.

The older I grew, the less sick I got, and the cleaner my voice became.

It wasn’t the same with my mouth.

The older I grew, the filthier it got, as though the phlegm that chafed my chords didn’t disappear, but instead became curses, and moved closer to my lips. Closer to the outside world.

This dirtiness sat, behind my teeth, under my tongue, for years.

It festered, and as an adolescent, I had many ulcers. I had pristine school reports, and my teeth were pearly white. But something in my stomach was pushing at my mouth. The skin broke open and my mouth bled, but my words stayed inside.

Then they slowly trickled out. They leaked between my teeth, through my parted lips, first in breaths, then whispers, then in words, and finally hacking coughs. My chest came full circle.

I think, sometimes, that my body formed around my mouth.

I think, sometimes, that my body formed around my mouth.With every cough a secret tried to escape. The belt of three stars, sea-salt drying on the shore, the taste of waves lapping against stones. My secrets, saffron kisses like warm winter tea, and words whispered like thin summer clouds.

But they were inside, pressed together, calcifying, not clouds anymore but slow rock, odorless in their immobility. In their imprisonment, tasteless.

Around them, my tongue morphed. My teeth, the teeth I ground to keep the clouds in, bled, then broke, then, around their debris, regrew anew. My lips flayed, then regenerated, and now they sit, my words’ sore and swollen gate to the world.

I think bodies form around their negative spaces.

I think bodies form around their negative spaces.Looking for someone else’s secrets, I found fossils in my ears. They looked like words, but ones I’d never heard before. They had been sitting for years, hardening, settling. The brackets that held my thoughts from tumbling, from the clouds.

I put the words back in, but my ears hadn’t stopped forming, deforming, reforming. The brackets were loose, the secrets ill-fitting, and the headaches started.

I think the words inside my body are the hammer to the anvil of the world outside.

I think the words inside my body are the hammer to the anvil of the world outside.I ignored the headaches. I was sure the problem was in the back of my neck. My skin crawled at the smell of saffron, the taste of sea salt. Every morning I’d wake to summer clouds, and my hackles would rise. Every night I’d sleep beneath three stars.

It had to be my dreams. They drained out like septic water every morning, clotting my hair, soiling my pillows. They never fit around my neck, until I redrew my head, re-stretched my spine, replaced my skin.

I slept better then, but I still ached. The sea salt was in my lungs, the sun’s fire in my gullet. I thought of bronchitis, like it were an old friend, and of words like “rock” and lungfuls of stones.

I think the spaces of my body work in tandem to stop it from being.

I think the spaces of my body work in tandem to stop it from being.I had been breathing smoke all my life.

Never a smoker when everyone else was (even the stars on moonless nights), I inhaled their tobacco breath and never breathed it out. It stayed in, pushed at itself. It coalesced, churning, flashing, a dense thundercloud of ever-changing unattainabilities.

Then I decided to sing again.

I sang in front of a mirror, “Watch your chin, your shoulders,” my instructor would say. But I watched my ears as they bled, my chest as it heaved. I watched the smoke leave my body.