“I Will Not Act in the World Before Understanding the World”: A Conversation with Alfredo Jaar

Tatiana Gómez

→MFA Graphic Design 2018

Alfredo Jaar is a Chilean artist whose conceptual work engages his audience in both intellectual and emotional ways, responding to contemporary ethics, politics, and violence around the world. His background in architecture and filmmaking—he never studied art—is reflected in the way he builds narratives using space, light, and language, among many other materials. This interview, which touches on topics from ambiguity and clarity to the artist’s responsibility in the world, took place in Spanish at the artist’s studio in New York City in March 2018. I translated it and co-edited both the Spanish and English transcripts with the artist.

• • •

TG: You work with both images and language. Can you tell me how you understand the relationship between ambiguity and clarity in language and how you apply it in your work?

AJ: Many of the pieces I have made are pure language. I have made work on paper, neon, and installations that are just text. When I use language, I rarely work with ambiguity. I try to be very clear. This does not mean that the texts I use cannot suggest different readings, even contradictory ones, but the very first meaning of the work is always a quite clear message. If some of my projects have any ambiguity, it is related to the poetic forms that I use in my work. For example, A Logo for America is a project on semiotics that I made back in 1987. My intention was to react against the shocking situation I confronted when I got to this country. I was horrified when I discovered that people said, “Welcome to America” and “God Bless America” when they were referring just to the United States, not the whole two continents. This was shocking to me. For me, America is North and South America and we are all American. Chileans are Americans, Colombians are Americans. The concept of America is treasured. There is a whole romanticism to being American, it has a rich history behind it. I was hurt to see that people from the United States had stolen the word America to refer just to their country. To me, this is a way to erase us from the map. So, when I was invited by the Public Art Fund to make a project, I took it as an opportunity to say something. You have seen it, right?

• • •

TG: You work with both images and language. Can you tell me how you understand the relationship between ambiguity and clarity in language and how you apply it in your work?

AJ: Many of the pieces I have made are pure language. I have made work on paper, neon, and installations that are just text. When I use language, I rarely work with ambiguity. I try to be very clear. This does not mean that the texts I use cannot suggest different readings, even contradictory ones, but the very first meaning of the work is always a quite clear message. If some of my projects have any ambiguity, it is related to the poetic forms that I use in my work. For example, A Logo for America is a project on semiotics that I made back in 1987. My intention was to react against the shocking situation I confronted when I got to this country. I was horrified when I discovered that people said, “Welcome to America” and “God Bless America” when they were referring just to the United States, not the whole two continents. This was shocking to me. For me, America is North and South America and we are all American. Chileans are Americans, Colombians are Americans. The concept of America is treasured. There is a whole romanticism to being American, it has a rich history behind it. I was hurt to see that people from the United States had stolen the word America to refer just to their country. To me, this is a way to erase us from the map. So, when I was invited by the Public Art Fund to make a project, I took it as an opportunity to say something. You have seen it, right?

Alfredo Jaar, Un logo para América, 1987, animación, 45 segundos. Imagen cortesía del artista.

Alfredo Jaar, Un logo para América, 1987, animación, 45 segundos. Imagen cortesía del artista.TG: Yes, of course! But I did not know that it had started as a commission by the Public Art Fund.

AJ: Yes. A Logo for America is a forty-five second animation that was shown every six minutes, in the middle of other ads, for a month. It was very controversial. It was in the newspapers, on the TV news, it turned into a media event. I was attacked from all fronts. Even National Public Radio sent a journalist to Times Square to interview people and ask them what they thought about the artwork. You could hear, live, on public radio, somebody say, “This is illegal! How did they let him do that?!”

This is a problem about education, and there is not much we can do about it. But more importantly, it has to do with the fact that language is not innocent. Language is a reflection of geopolitical reality. Therefore, as the United States rules the continents, it is very obvious that, through language, they also dominate the name of the continents. That political, cultural, and social control is reflected in language. And this is something that is not going to change until the domination of the empire of the United States over the continents ends. It is sad, but it is true. It is the geopolitical reality we live in. So, this is how what started as a semiotic piece about language ended up being a very successful project. It is my most reproduced artwork in art books and in school books.

TG: In school books here in the United States? You entered the education system then!

AJ: Yes, school books that are teaching children what America really is. Twenty-seven years later, in 2014, the Guggenheim Museum acquired the animation and to celebrate their acquisition, decided to show it in Times Square again. But Times Square had changed since 1987. Then, there was a single electronic sign, while in 2014 there were more than a hundred and twenty. You have seen how it looks today, correct?

TG: Sure, it is crazy.

AJ: So, in August 2014 at midnight we screened it again simultaneously on sixty signs and repeated it over three days. It was amazing! But something quite extraordinary happened. This work was born as a semiotic project—I have always been very interested in language, semiotics, and signs—but in 2014 the reading of the animation changed. It changed because the Obama administration was in the process of expelling millions of immigrants, almost four million of them. So the meaning itself of being American was being questioned. People were talking about it. Mexicans and Latin Americans in general, some here illegally, were saying, “I am American too.” So in 2014 nobody is talking about the language issue, no, people are talking about the significance of being American. After that, we showed it in Mexico and in Piccadilly Circus in London. The Guardian published an article called “Anti-American Art,” which read the piece as anti-American, when in my opinion there is no artwork as American as this one.

In conclusion, I can say that I completely lost control over this work. And this is one of the cases where, for me, language is not ambiguous at all, it is a reflection of power. Whoever has the power controls the language and adjusts it to their own convenience. This is what is so extraordinary about power. Whoever has the power says: this word means this, but from now on, I decide that it is going to mean this other thing. There is nothing ambiguous about that.

TG: I am intrigued by the Guardian response because I have been thinking for a long time that this way of referring to the United States as America actually comes from the British.

AJ: Well yes, this situation is quite generalized in Europe. When I go to Italy and my friends tell me, “I am going to America next week” I am always correcting them. “Do you mean you are coming to the United States next week?” “Yes, right, I am sorry.” This problem is part of the universal language and is transmitted worldwide through the media, and we have no control over it.

TG: I also want to ask about your perspective on the clarity and ambiguity of visual language.

AJ: It all depends on the goal of the artist, but as I said, I generally do not use ambiguity in my work. For example, in 1992 I made a work titled 1992. In that moment, the European Union was starting to close their borders and expel immigrants. I thought that Europe could sadly become an anti-immigrant fortress, which is exactly what is happening nowadays. So I made this piece where you can see, at the bottom, a section of the flag of the European Union—with the blue background and yellow stars representing the countries of the Union. On the top, I used a horrific fence, an image from a concentration camp for Vietnamese refugees in Hong Kong. There is no obvious sign that this place is in Hong Kong, so I decided to use this image as a generic one to suggest that Europe was becoming a prison. The composition implies that the circle of stars completes itself with the symmetry of the image of the fence. To me, there is no ambiguity in this piece. I am sending a clear message about what is happening in Europe in 1992. Now it has become so pertinent that we are going to show it again. People will see it and will understand that things have not changed, at least since 1992. So, there are artists who use ambiguity but, I am very Cartesian, and I try to make sense.

Alfredo Jaar, 1992, 1992. Image courtesy the artist.

Alfredo Jaar, 1992, 1992. Image courtesy the artist.TG: Yes, you are very generous with your audience and also very responsible. I have read about your research process, how you understand a topic you work with before you decide to bring it to the light. What do you think about your responsibility as an artist?

AJ: This comes from my architecture background. I studied architecture, I never studied art, and for architects, context is everything. For an architect it is impossible to think about starting a project in a specific place without having an understanding of, for example, where the sun rises. Or where is the wind, how is the soil, who lives next door, who is in front? Where does this road take you? These are basic things that, believe me, artists sometimes do not even ask. They make art while totally ignoring the context. To me this is unconceivable. I am an architect who makes art and I use the methodology of architecture where the context means everything. Therefore, my modus operandi, my manifesto is this:

“I will not act in the world before understanding the world.” In my practice, the process of research, of understanding the place before acting, is very important. I act only when I reach a certain level of responsible understanding. Only when I fully understand the place do I allow myself the right to formulate ideas, thoughts, and speculations about the place. When I visit a place for a couple days, people invariably ask me: “Do you have any ideas?” No, I do not have any. When I was younger I could have ideas in two seconds. But I have done this for so long that I have trained myself and reached a point where I know how to control myself and I do not allow my brain to think about any ideas because they are very likely to be stupid. They will not resist the passing of time if I have not fully understood the place.

TG: As a graphic designer I relate very much to your research process, but I wonder: How do you digest all the information you work with? Do you have a formula to balance the strong topics you constantly work with? Does it ever become an overwhelming task?

AJ: Well, I am used to it. I have always done it like this and I have grown a sort of alligator skin, if you know what I mean. I think we can all develop these psychological or mental abilities to deal with certain tasks. It takes time and a lot of experiences in different places on the planet—many of them terrible ones—but I have built psychological tools to be able to do this kind of work.

TG: The Rwanda Project—a series of projects in response to the Rwandan genocide in the mid-1990s—involved a very long and I would imagine very difficult process. Can you tell me more about this particular experience?

AJ: I worked on that project for six years and it probably would take forever to explain it in detail. But to answer your question, I can say that I faced a very hard situation in Rwanda, the hardest I have ever had in my life, and I did not have any answers. Nobody had answers for that horror. What I did is that I collected data to try to understand, to be responsible with the material I had. Then I decided to turn the Rwanda Project into a series of exercises. I knew that I was going to fail, so the exercises were failed exercises even before starting them. It was a situation I did not master. I had never done something like this, so I was just going to make exercises. I wanted to learn from each of them and be able to apply what I had learned to the next exercise. That is what I did and I ended making twenty-five projects in six years. The exercises relieved me from the fear of failing, allowed me to learn but also to release everything I had accumulated inside of me. In the end some of the projects ended up being better than others, but the most important thing is that I learned so much through those six years. I always say that in my career there is a pre-Rwanda and a post-Rwanda. The strongest effect that it had in my practice was that I had always used photography in a more indiscriminate way that I do now. After Rwanda I learned to have much more respect for the images I work with and to use fewer images. I think that this summarizes what Rwanda represents for my practice.

TG: I want to ask you about your relationship with Chile nowadays. You left the country in a very complex moment and since, it has changed a lot.

AJ: Yes, I left Chile in 1982 in the middle of the dictatorship. I did not show my work there until 2006, when I returned with a large retrospective. At that moment, a beautiful encounter was triggered with the new generation of artists, and since then I have had a much better relationship with my country. Also, we are now a democracy. I had a lot of trouble with people from my generation when I lived in Chile, so I have always felt like there is a chasm between us. But with the new generations, things are different. I come back to Chile with pleasure now and I have had small exhibitions there once in a while. Now people there—from the art world and also the general public—know about my work. In 2013 I got the National Prize of the Arts (Premio Nacional de Arte). I also created a memorial for the victims of the dictatorship for the Museo de la Memoria in Santiago. This work gives me a certain presence in Santiago as it is part of the permanent collection. All these things have straightened my presence in Chile’s cultural life.

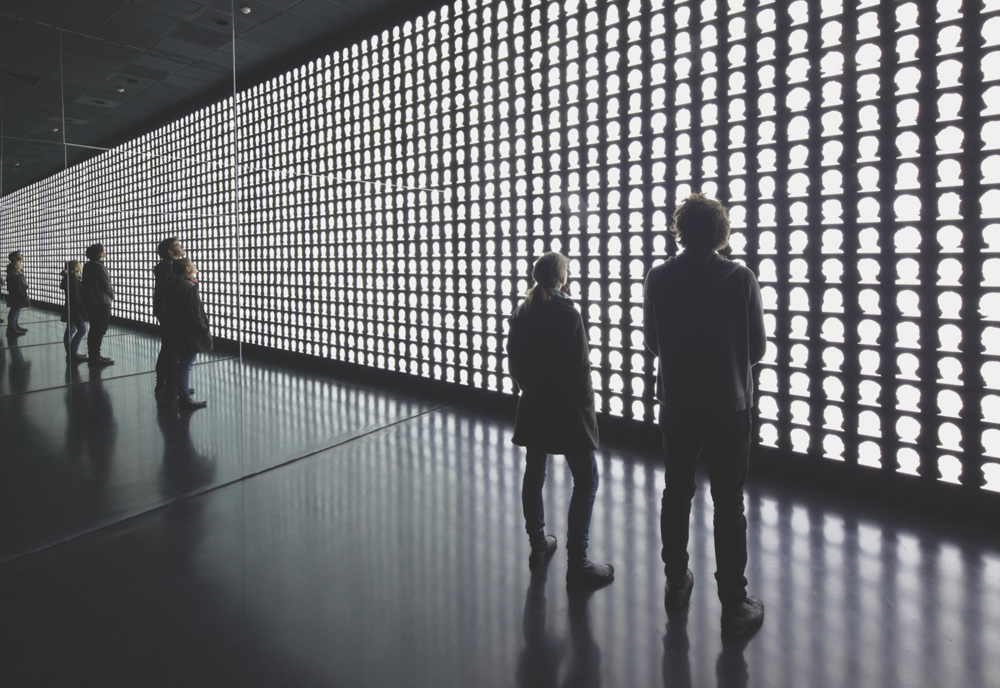

Alfredo Jaar, The Geometry of Conscience, 2010. Museo de la Memoria, Santiago de Chile. Image courtesy the artist.

Alfredo Jaar, The Geometry of Conscience, 2010. Museo de la Memoria, Santiago de Chile. Image courtesy the artist. TG: Your piece at the Museo de la Memoria is so beautiful. I am happy that Chileans have the chance to experience your work at home now. I have one last question. I know that you start your day reading newspapers from all over the world and accumulating information from different sources. In terms of politics, what is on your mind these days?

AJ: I think that our generation is facing an unprecedented political reality. I find it exhausting, depressing, and I think that, until now, we have not found the right models, in the world of culture—nor in the political world either but I am interested in culture—to react to this new political reality that we are living in, in this country and in the world. It is a world-wide phenomenon. Trump is not alone, a dozen fascists like him have emerged in Europe, Asia, and Latin America. We are living a sort of new fascism that makes me very nervous. And I am very pessimistic in this regard, as I do not see that the opposition to these fascist winds has created an adequate model to counteract, to confront them, to defeat them. And that is where we are.

TG: That is why we need to keep making art.

AJ: That is right.

TG: Thank you, Alfredo.