English Is a Torrent

English Is a Torrent

Ryan Yan

→ BFA GD 2025

English is hard; the rigid enforcement of “proper” English demands adherence from a system filled with contradictions. Why are “cough,” “though,” “through,” and “tough” all pronounced differently? Why does “knight” hide half its sounds? And what’s up with the deadly homophonic trio of “there,” “they’re,” and “their”? Why don’t the sounds and spellings in English line up? This isn’t aksidental—it emerges from the ongoing tenshun between power strukchures imposing standardizshun and communities activly rezisting these norms.

Historically, English has always had a voracious appetite for linguistic borrowing, collecting more and more words with sounds our writing system couldn’t represent. Our alphabet, composed of 26 letters, is stretched thin over 44 phonetic sounds, making writing English an Oulipian exercise in representation. This lexicon borrowing brings orthographic ghosts from their languages of origin, forcing the English writing system to evolve away from the uniform ideal attempted by colonial Britain.

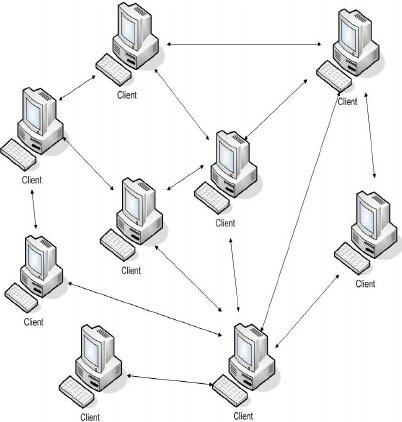

Peer to Peer network (Diagram from “Architectural model for Wireless Peer-to-Peer (WP2P) file sharing for ubiquitous mobile devices” (2009), Ayodeji Oluwatope et al.)

Today, digital spaces open up new possibilities for orthographic adaptations, deployed and distributed in something closer to guerrilla tactics rather than an organized effort. Our language network might seem like an open source project—a communal effort we all contribute to—but the absence of organized repositories,

documentation, and governing maintainers who approve or reject changes makes it more like a torrent system. With no central server hosting definitive meanings, cultural understanding is seeded peer-to-peer across overlapping networks as users simultaneously download and upload fragments of meaning. This torrent-like quality means that no single source ever possesses the complete codebase of our language. Its inaccessibility creates spaces where communities can develop their own linguistic sovereignty away from dominant culture’s standardizing impulses.

Power Systems Shape Writing Systems

Writing systems have never been neutral reflections of language, but rather technologies wielded by those in power. From the Roman Empire’s spread of the Latin script (also known as the Roman script, used interchangeably in this article), to the Cyrllic-based scripts that replaced Arabic scripts in Central Asia, powerful states have long recognized that controlling how people write is nearly as important as controlling what they write.

The standardization and policing of written language is achieved through orthography, the system governing how a language is represented in written form. It’s a broad blueprint that determines which symbols correspond to which sounds, how words are segmented, and how grammatical features are marked on the page. The term derives from Greek orthos (correct) and graphein (to write)—its normative function embedded from the very beginning. Sociolinguists assert that “orthography is one of the key sites where the very notion of “standard language” is policed.”1 This policing of correctness is often systemic and institutionalized, from academic style guides to publishing houses, to classrooms and standardized testing.

With the imposition of orthography comes potential for faulty transliteration between languages. Romanization systems map Latin characters onto diverse phonological systems with little consistency across languages. Some letter combinations suddenly contradict expectations, producing completely different sounds depending on linguistic context. Ironically, the Latin alphabet wasn’t even designed for English. It was created, well, for Latin. Nevertheless, the Latin alphabet has become a “global script”—for roughly 70% of languages worldwide—pressed into service for languages it was never designed to accommodate.2 Yet this ubiquity creates a dilemma: while the Roman script makes languages more legible in a global audience, it simultaneously flattens their rich phonetic landscapes. Tones, glottal stops, and the musical rhythms of speech dissolve into silent letters. This standardization isn’t neutral, instead privileging certain ways of speaking while erasing marginalized communities. But what’s the most fascinating, is how communities are resisting homogenization by reclaiming the Latin script with our new technologies.

With just the clicks of our fingers now, digital communication creates turbulent spaces where language is sampled, remixed, and transformed through community usage rather than institutional decree. When Jamaican Creole speakers write “yaad” for “yard” or “wid” for “with” in their texts, they're making deliberate choices to preserve vernacular authenticity and establish community boundaries, holding language close from the scripted pull-away of autocorrect. Similarly, in Singapore, Singlish orthography flourishes online despite the government’s official Speak Good English Movement.3 Discourse particles like “lah,”, “lor,” and “leh” and distinctive spellings like “liddat” for “like that” become assertions of a multilingual identity that resists both standard English dominance and language purism policies.4 I try to play a small part in the quiet rebellion against linguistic homogenization too by stubbornly keeping my keyboard set to Canadian English, deploying “colour” like a small flag of resistance against the wave of red squiggles. The “I'm not American!” signal, while definitely annoying enough for a lot of my friends, immediately creates a connection with fellow Commonwealth spellers; a single “u” becomes an unlikely but effective community marker.

The Internet was Built for English

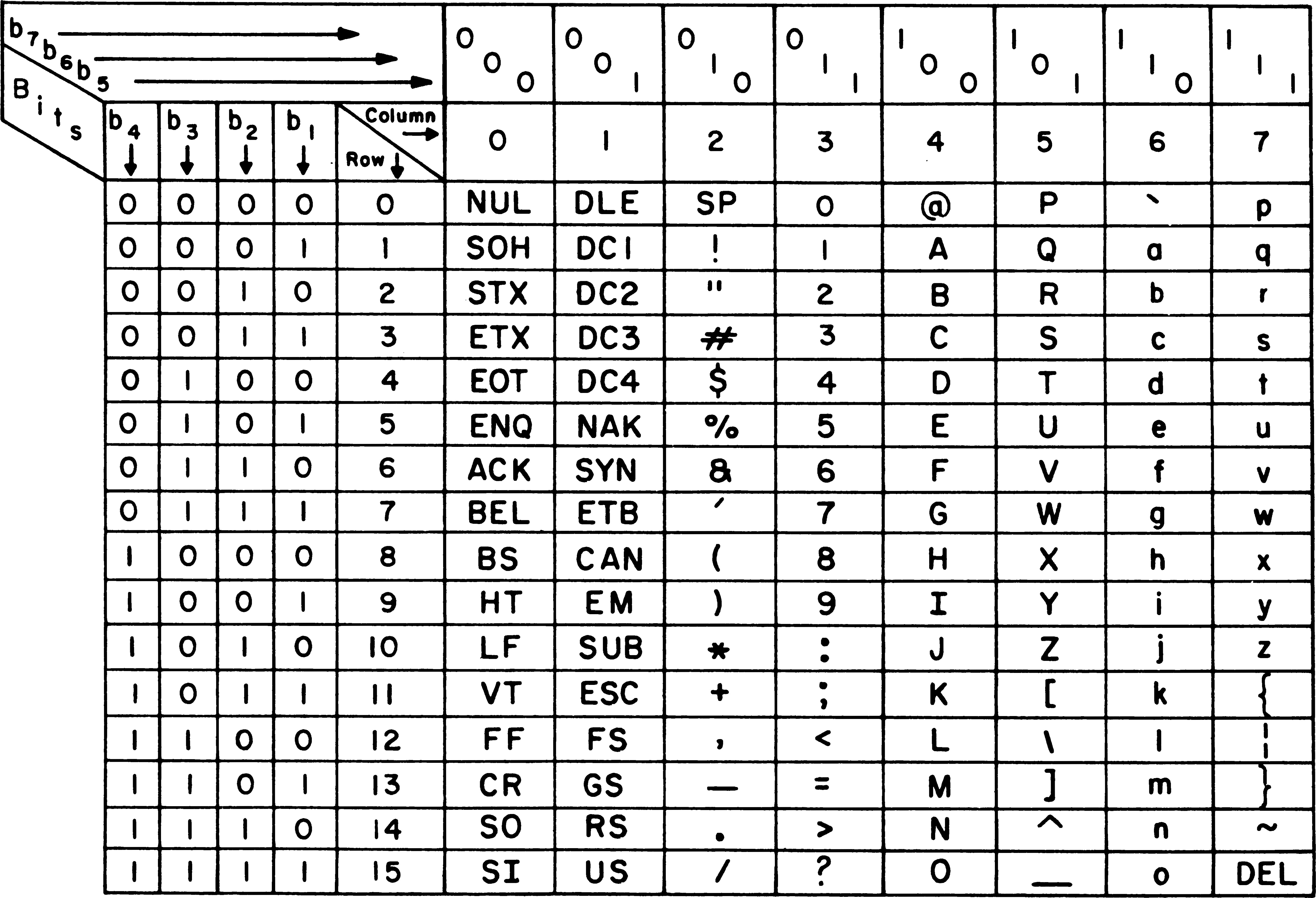

Could our resistance against the red squiggles be part of a bigger struggle against the internet’s systematic enforcement for language standardization? The Internet’s climactic rise made a thrilling promise of liberating communication. But it came with a caveat. Digital orthography, language transcription on the internet, was designed with architectural decisions that privileged language communication in English. Born in the labs of the American defense establishment in the 1960s, the internet’s foundation rests on ASCII (American Standard Code for Information Interchange)—a character encoding standard supporting only 128 characters, comfortably adequate for English but woefully insufficient for most of the world’s writing systems.

https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:USASCII_code_chart.png

ASCII’s limitations reflected the practical priorities of its American developers who were primarily concerned with standardizing computer communication in English. The resulting character encoding standard created an electronic medium that inadvertently privileged Latin-based scripts while presenting significant challenges for other writing systems. As the internet expanded globally throughout the 1980s and 1990s, the Latin character set became the internet’s de facto linguistic currency—a medium of exchange that non-English users were forced to adopt despite its poor exchange rate for their native scripts. This technical foundation highlighted previously blurred boundaries between English as a language, English orthography, and the Latin character set itself, as users worldwide had to consciously navigate these distinctions to participate in digital communication. This created a peculiar scenario where billions of people, as they connected to the rapidly expanding internet, found their native scripts unsupported by the very technology promising to connect humanity.

Faced with this digital “straightjacket”, language communities worldwide developed workarounds that transformed constraints into creative opportunity. Arabic speakers repurposed numerals as visual stand-ins for sounds without Roman equivalents, with <3> representing <ع> and <7> standing in for <خ>. Greek users similarly employed visual equivalence, substituting <w> for <ω> and <8> for <θ>, much to the horror of the Academy of Athens, who promptly declared such adaptations are “a threat to the Greek language.”5 What language purists and institutional authorities often label a “language crisis” might better be understood as the birth pangs of new digital language conventions. Languages with Cyrillic alphabets underwent similar transformations—eliminating diacritic marks, substituting vowels and modifying consonants—not as a surrender to English dominance but as tactical adaptation. Even as Unicode, an expanded standard for online text encoding, eventually widened our digital character set, these early adaptations created a new set of needs in digital orthography: a distributed, community-driven approach to digital communication, something that could maintain distinctive linguistic identity with limited tools.

The adaptive results of early internet constraints reveal a common pattern: humans bending technical systems to serve communicative needs rather than the reverse. Just as linguists recognize language change as an inevitable process driven by natural adaptation, digital platforms serve as their own ecosystems where non-standard forms naturally emerge in response to developing technical and social constraints.6

Technologies Perform Language Compression

Long before the globalization of an English internet, communication technologies were already forcing us to reimagine how language could function and look. Together with the desperate need to optimize efficiency of time, space and capital, our orthographies shift from mechanical limitations to cultural signifiers.

When telegrams first connected our world in the 1860s, language underwent a radical “compression” driven by economic necessity. At nearly $100 for just twenty words, early messages sparked elaborate coding systems where single words represented entire phrases, introducing “a clipped way of writing which abbreviates words and packs information into the smallest possible number of words or characters.”7 Mining companies developed codebooks where words like “REVERE” weren't even acronyms, but compressed versions of full sentences like: “WIRES BEING DOWN, YOUR TELEGRAM DID NOT REACH US IN TIME TO TRANSACT ANY BUSINESS TODAY, AND AS YOUR ORDERS ARE GOOD FOR THE WEEK, WE WILL TRY TO EXECUTE TOMORROW.” This served as a fundamental reimagining of how meaning could be packaged and transmitted. Companies even debated whether “MAGFDYHFJU,” which decompressed to “Delivered in time to San Francisco,” could be sent as one chargeable word instead of two.8 Language was a commodity, measured and priced by the character.

As telecommunications evolved through the 1990s, economic pressure gave way to new mechanical constraints. The introduction of mobile phones with nine-key T9 keyboards had users navigating multiple letters per key. So, we developed novel shortcuts, not primarily to save money, but to save precious thumb movement. “l8r” and “gr8” became practical solutions to a physical problem. This era of abbreviation began to wane with the introduction of full QWERTY keyboards on phones, followed by increasingly sophisticated smartphone keyboards. With these advancements, “l8r” eventually became slower to type than just “later” once digital keyboards required users to switch to the number interface just to reach “8.” Despite this technological evolution, the early 2000s saw new platform constraints emerge with character limits on Twitter and other social media revitalizing abbreviations to preserve digital space.9 Simultaneously, popular media embedded these texting conventions into depictions of youth culture, elevating compressed forms from mere conveniences into markers of generational identity. Beyond understanding the wordplay of “8” as a phoneme of “ate,” these patterns demonstrate how language can be packaged with cultural context. Even as typing technology continues to improve, expressions like “u r” and “lol thx” remain as signals of digital community membership.

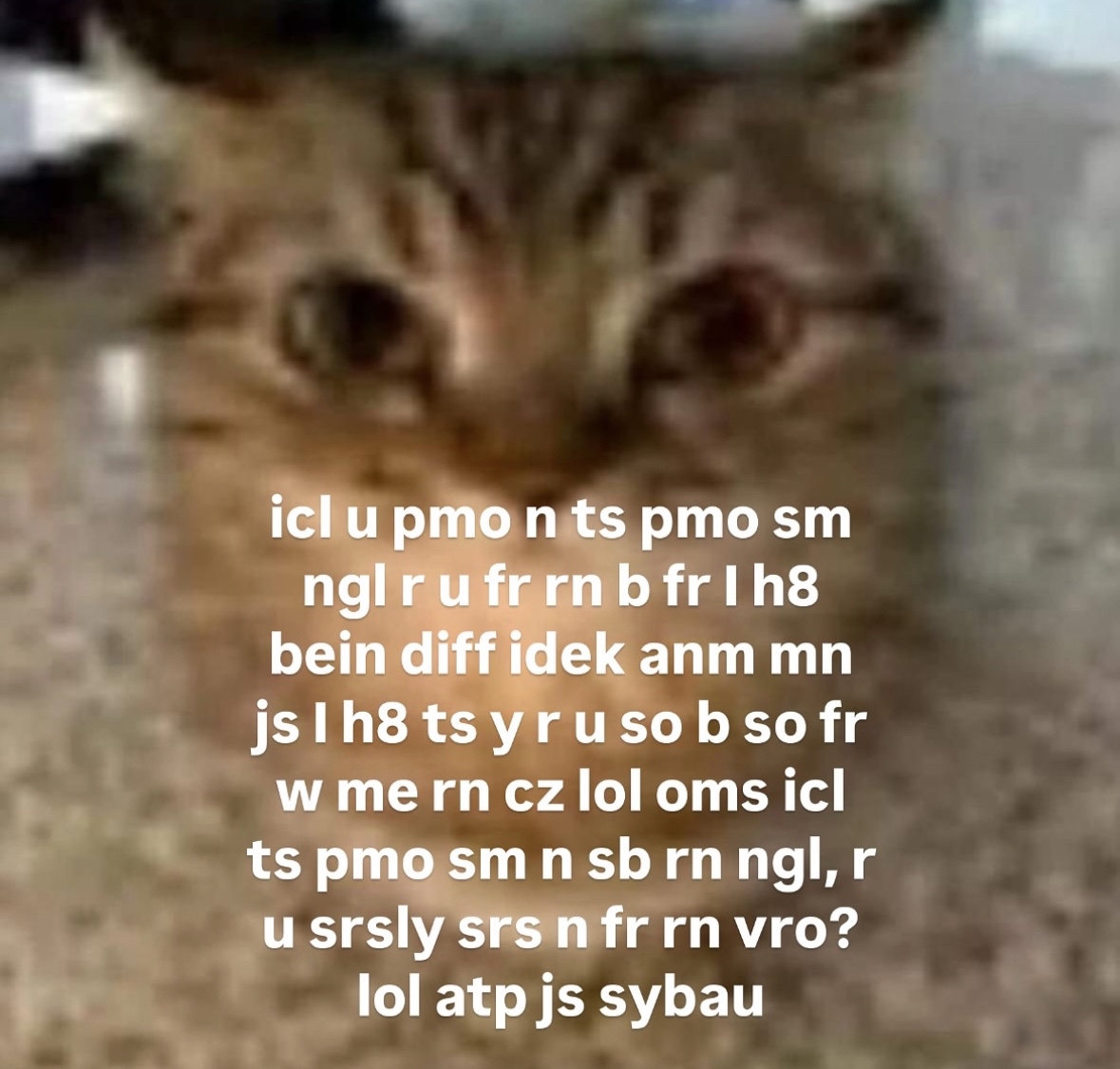

Compression and decompression isn't just about shortening and decoding words though—it’s a cultural methodology of packing complex meaning into minimal forms. Consider memes, where a single image with brief text can convey elaborate cultural narratives, inside jokes, and political commentary that might otherwise require paragraphs to explain. Similarly, linguistic compression condenses identity markers and social positioning into efficient typographic packages. The receiver then decompresses these signals, extracting layers of meaning beyond the literal text. This process transforms simple orthographic decisions into rich conveyors of sociocultural positioning—all without requiring explicit explanation.

In traditional semiotics, meaning emerges through the relationship between sign, signifier, and interpretant—a framework for understanding how we derive meaning from symbols. But in digital semiotics, even the subtle choice between “u r,” “U R,” “u are,” “you are,” or “you're” can decompress differently depending on who’s receiving your message. Something as simple as capitalization is a compression of social signals: From using aLtErNaTiNg CaPs to convey mockery, to turning off auto caps for texting, and even unconsciously Title Casing Your Sentences to signal political affiliation.10, 11These patterns transform ordinary text into paralinguistic markers. Even the ™ symbol can be used to turn words into mock-proprietary concepts, functioning as “honorary proper nouns, like the linguistics version of Gretchen Wieners trying to make Fetch™ a thing in Mean Girls.”12

Our digital texts are highly referential, requiring shared knowledge of the cultural weight each compression carries. Feeds, algorithms, and online social circles form these unique semantic anchors, exemplified through the hacker subculture language of leetspeak (“1337”) to the localized typographies of laughter across global scripts.13

But while linguistic content can be compressed across digital spaces, the emotional and contextual cues of communication remain difficult to package. The reduced social cues (RCS) model suggests that text-based communication loses crucial social signals present in face-to-face interaction, yet rather than making conversation “less fluid,” online communities actually develop what some researchers call “textual paralanguage”—written manifestations of nonverbal audible, tactile, and visual elements.14

Recently I’ve been noticing rise in these “acronym chaining” memes, perhaps as an ironic response to the heightened misuse of acronym usage—its form is reminiscent of comprehension practices in early telegram messages.

But while linguistic content can be compressed across digital spaces, the emotional and contextual cues of communication remain difficult to package. The reduced social cues (RCS) model suggests that text-based communication loses crucial social signals present in face-to-face interaction, yet rather than making conversation “less fluid,” online communities actually develop what some researchers call “textual paralanguage”—written manifestations of nonverbal audible, tactile, and visual elements.14

Economy of Time/Cues and Tone

Our faster, more direct modes of digital communication demand new techniques for compressing social cues through orthographic choices. Text stretching (“nooooooo”), keysmashing (“asdfghjkl”), punctuation repetition (“????”) are just some examples of these innovations we created to be visually processed as emotional shorthands.

Emojis and emoticons are primary examples of these “elaborators,” created in the 1980s and 1990s when the “promise of digital communication … was being offset by this accompanying increase in miscommunication.”15 Intended to facilitate the missing contextual information, these visual elements serve as semiotic resources that translate potential nonverbal communication elements into text. Emojis have since evolved beyond tone clarifiers into social markers, as their usage and employment signal differently across communities.16 These “virtual communities of practice” developing specific linguistic norms, such as capitalization patterns, that become part of their distinctive sociolects.17 In text-based communication that lacks traditional paralinguistic cues, these seemingly chaotic texting practices actually reveal a system of social positioning and community membership that continues to evolve.

But perhaps the bleaching of emojis over time has reached a point where they are no longer effective in communication anymore. Maybe we should try something new that could explicitly mark intent rather than rely on increasingly ambiguous symbols.

A text from my partner last year that sparked my initial research

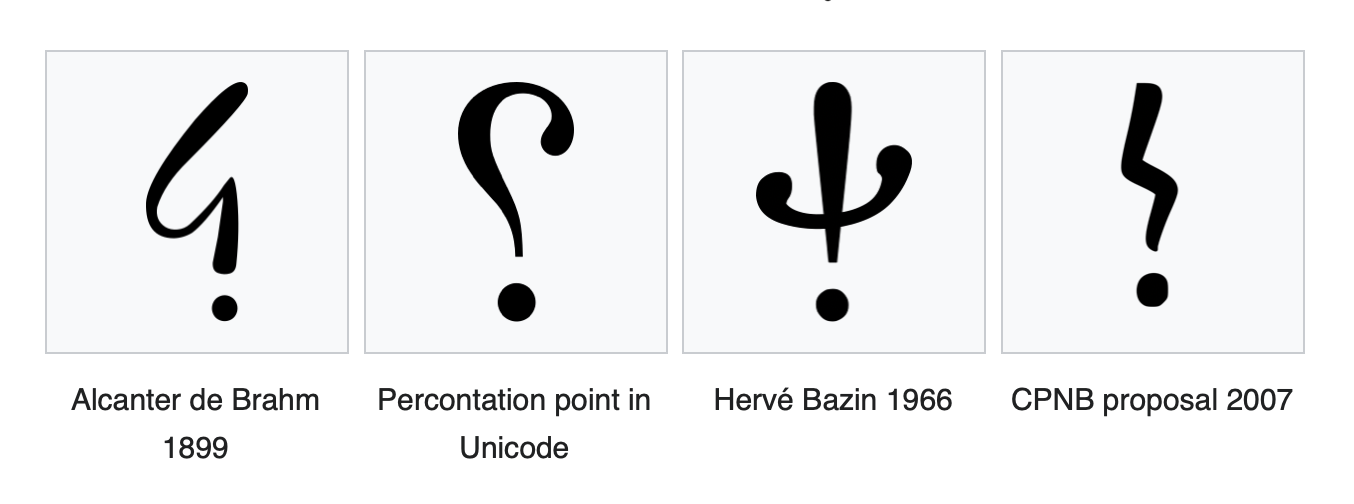

Tone indicators (like “/s” for sarcasm, “/j” for joking) emerged from neurodivergent communities online addressing the fundamental challenge of conveying tone without vocal inflection or facial expressions. They represent an accessibility solution to a universal digital communication problem—how might we make our intended meanings clearer when stripped of physical cues?

And yet, these indicators aren’t revolutionary innovations so much as digital manifestations of historical punctuation experiments. The percontation point(?) for rhetorical questions and irony mark (¡) for ironic statements represent previous attempts to solve this same puzzle. Are . ? ! really sufficient for capturing the full spectrum of expression through text? These historical marks didn’t disappear because they were rejected outright, but because they simply weren’t circulated enough to achieve critical mass.

Language innovations, like the digital files of a torrent, require continuous circulation to remain viable. Without sufficient sharing and usage, they drop from our collective network. Tone indicators now sit at this inflection point—will they achieve the widespread adoption needed for permanence or fade like their punctuation predecessors?

But alt text provides the alternative outlook—once considered niche, it’s now gradually becoming standardized across platforms as accessibility awareness grows. Both represent a kind of parallel track of meaning, available but not intrusive. Perhaps the right question isn’t if these tools should be universally mandated but how they can find their natural positioning in our digital ecosystem or even mark the boundaries of communities.18

The Myth of Universal Communication

These communities, once bound by geography, are now bound by accessibility, formed through the intersubjectivity of internet communication. But unlike the telegraph’s codebooks or computer program documentations, our internet language doesn’t have a handbook that grants us access to every convention and poetic function.

This is particularly prominent in what’s noted as a “gentrification of AAVE” into what’s now labeled as TikTok “brainrot” language.20 Expressions with significant cultural and historical ties to Black and Queer communities are stripped of their contexts, redistributed through algorithmic amplification, and consumed as novelty in the attention economy. The compression efforts of packaging cultural context into linguistic conventions is nonconsensually extracted, mirroring a process of non-Roman scripts undergoing systematic transformation at the hands of dominant writing systems—in both, powerful forces impose standardization that serve dominant groups while erasing cultural context.

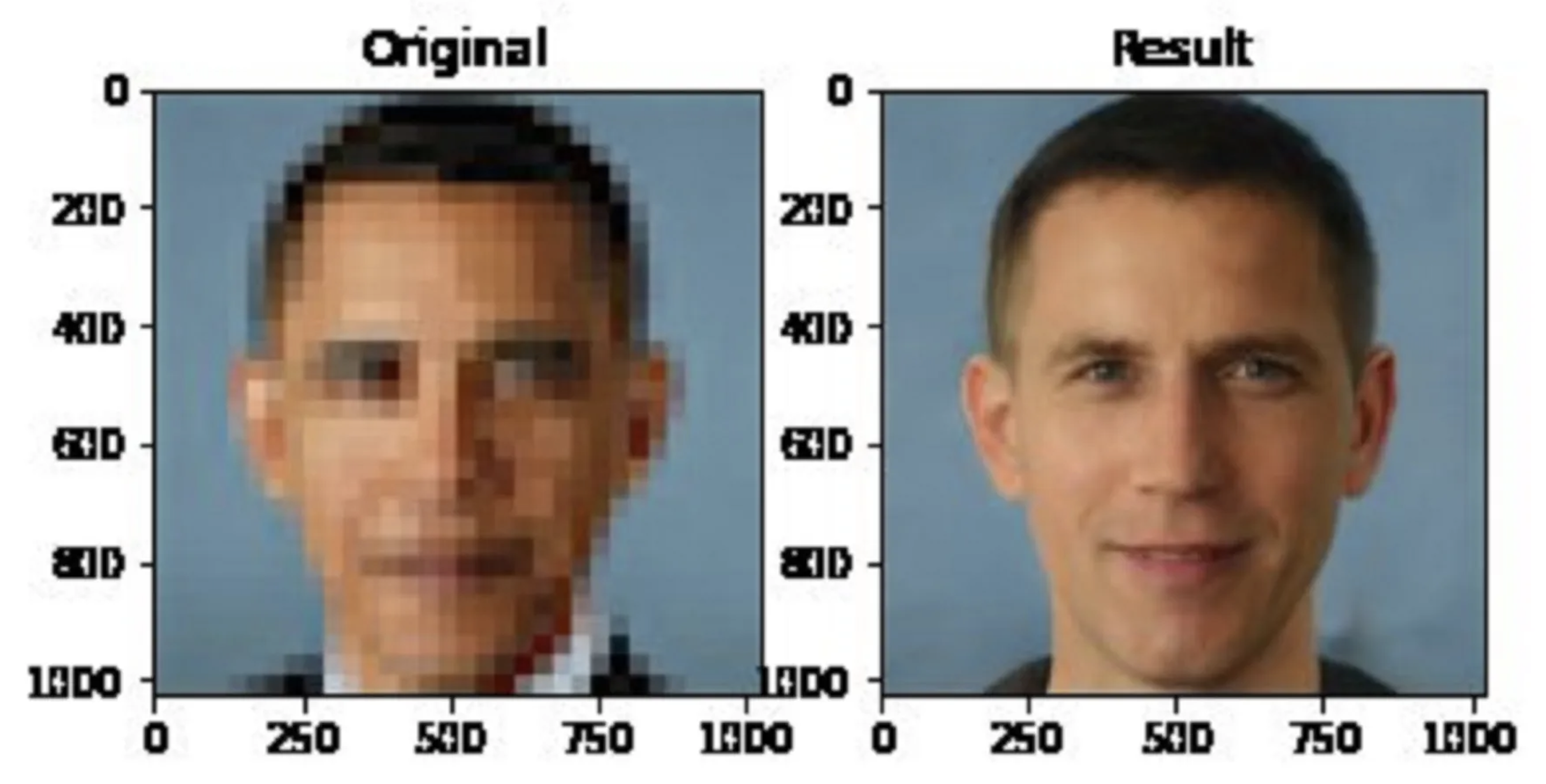

Barack Obama becomes a white man through image upsampling (Image: Twitter / @Chicken3gg)

Perhaps the most insidious danger lies in how this process reinforces existing power dynamics while masquerading as democratic language evolution. The torrential nature of internet language means we’re all consuming meaning, while simultaneously participating in a form of semantic bleaching by propagating corrupted linguistic fragments. So even though platforms create spaces where language transforms through community usage rather than institutional decree, we should always be questioning who benefits when linguistic innovations become commodified. Just as torrent networks operate beneath official channels, our linguistic innovations flourish in these same unregulated spaces. But these parallel decentralized networks risk becoming potential sites of extraction in this site built to uphold colonial English. The very qualities that make torrenting powerful now render our linguistic expressions vulnerable to higher dimensional forms of surveillance and commodification.

In the distance, a brewing storm sweeps through our communities and pummels our language into raw tokenized material. Conventions once born through technological constraints, shaped by social practices, and evolved into sociolinguistic markers, are now consumed and produced without cultural agency. In this next era of digital text, as community tools are stripped of their resistance and boundaries are flattened into probabilities, what becomes of our language when machines start torrenting us?

For further reading: McCulloch, Gretchen. Because Internet: Understanding the New Rules of Language, 2019

Ryan Yan is asdfghjkl…??

Notes

- Jaffe, Alexandra. 2000. "The Voices People Read: Orthography and the Representation of Non-Standard Speech." Journal of Sociolinguistics 4 (2): 561-87.

- Encyclopædia Britannica. n.d. "The World's 5 Most Commonly Used Writing Systems." https://www.britannica.com/list/the-worlds-5-most-commonly-used-writing-systems.

- Deuber, Dagmar, and Lars Hinrichs. 2007. "Dynamics of Orthographic Standardization in Jamaican Creole and Nigerian Pidgin." World Englishes 26 (1): 22-47. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-971X.2007.00486.x.

- Wong, Tessa. 2015. "The Rise of Singlish." BBC News, August 6, 2015. https://www.bbc.com/news/magazine-33809914.

- Themistocleous, Christiana. 2010. "Online Orthographies." In Handbook of Research on Discourse Behavior and Digital Communication: Language Structures and Social Interaction, edited by Rotimi Taiwo, 267-79. Hershey, PA: IGI Global. https://doi.org/10.4018/978-1-61520-773-2.ch020.

- Ekayati, Rini, et al. 2024. "Digital Dialects: The Impact of Social Media on Language Evolution and Emerging Forms of Communication." International Journal of Educational Research Excellence (IJERE) 3 (2): 605. https://doi.org/10.55299/ijere.v3i2.986.

- "Telegram Style." n.d. Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Telegram_style.

- Bellovin, Steven M. 2025. "Compression, Correction, Confidentiality, and Comprehension: A Modern Look at Telegraph Codebooks." Cryptologia 49 (1): 1-37.

- Boot, Arnout B., et al. 2019. "How Character Limit Affects Language Usage in Tweets." Palgrave Communications 5 (1): 76. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-019-0280-3.

- Jobe, Nyima. 2025. "The Death of Capital Letters: Why Gen Z Loves Lowercase." The Guardian, February 18, 2025. https://www.theguardian.com/society/2025/feb/18/death-of-capital-letters-why-gen-z-loves-lowercase.

- Tatman, Rachael. 2017. "Can Your Use of Capitalization Reveal Your Political Affiliation?" Making Noise and Hearing Things (blog), July 29, 2017. [URL to be added]

- Gallucci, Nicole. 2019. "A Look at the Ubiquitous Habit of Capitalizing Letters to Make a Point." Mashable, June 18, 2019. https://mashable.com/article/capitalizing-first-letter-words-trend.

- Grundlingh, Lezandra. 2020. "Laughing Online: Investigating Written Laughter, Language Identity and Their Implications for Language Acquisition." Cogent Education 7 (1). https://doi.org/10.1080/2331186X.2020.1833813.

- Luangrath, Andrea Webb, et al. 2017. "Textual Paralanguage and Its Implications for Marketing Communications." Journal of Consumer Psychology 27 (1): 98-107. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcps.2016.05.002.

- Blagdon, Jeff. 2013. "How Emoji Conquered the World." The Verge, March 4, 2013. https://www.theverge.com/2013/3/4/3966140/how-emoji-conquered-the-world.

- PLOS. 2024. "Emojis Are Differently Interpreted Depending on Gender, Culture, and Age of Viewer." ScienceDaily, February 14, 2024. https://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2024/02/240214150229.htm.

- Neus, Andreas. 2001. "Managing Information Quality in Virtual Communities of Practice: Lessons Learned from a Decade's Experience with Exploding Internet Communication." In Proceedings of the Sixth International Conference on Information Quality at MIT, edited by Elizabeth Pierce and Richard Katz-Haas, 148-60. Boston: CiteSeer.

- Koebler, Jason. 2016. "Why a Universal Language Will Never Be a Thing." Vice, April 22, 2016. https://www.vice.com/en/article/why-humans-dont-have-a-universal-language/.

- Koebler, Jason. 2016. "Why a Universal Language Will Never Be a Thing." Vice, April 22, 2016. https://www.vice.com/en/article/why-humans-dont-have-a-universal-language/.

- Lacey, Kyla Jenée. 2022. "Labeling AAVE as Gen Z, TikTok Speak Is Appropriation." TheHub.news, November 28, 2022. https://www.thehub.news/labeling-aave-as-gen-z-tiktok-speak-is-appropriation/.