When Hope Walked Through the Door: To Every Orange Tree (A Review)

Anonymous

→BFA 2026

All images by the author and RSJP.

“What would a moment of peace look like? How can you frame [Palestinian solidarity] as a celebration of life and living so we know what we’re fighting for?”

—RSJP member

My steps were rushed, but somehow they dragged. Nowadays, I shrink into my shoulders, avert my eyes, and withhold breath. All in all, something like an ostrich. I came to the US with hopes of safety secured by a student’s “temporary contract” to be here, under the bygone assumption of American liberalism. That hope dissipated long ago.

I was on my way to the opening of the show To Every Orange Tree, organized by members of RISD RSJP (RISD Students for Justice in Palestine), which opened at AS220 on November 1st. In my time at RISD, I mostly watched the many student protests from afar. Even back at home, I was never too involved in activism. For much of my life, I believed I had little agency, and I would never be able to vote. That sentiment, that lack of courage, had lingered, blanketing over how I interpreted everything that was happening. The minute I entered the show, though, something shifted.

There was nothing but joy and celebration in the air. Song and conversation filled the room. A local musician sang merrily about life (albeit under capitalism and fascism), and at one point, a faculty member passed out triumphant red carnations for all the student organizers. I had never seen a show that was so LOUD: with solidarity and with hope.

I admire my peers, members of RISD RSJP, deeply for their resilience. RISD RSJP is a chapter of the National Students for Justice in Palestine. In the past two years, they mobilized a relentless series of protests, culminating in an encampment in 2024. Students from RSJP occupied and renamed the Prov Wash building Fathi Ghaben Place, and issued demands for RISD to divest from Textron and provide full financial transparency in RISD’s investments. They encountered significant pushback, from their demands not being met to their initial installation of To Every Orange Tree in Carr Haus going awry. This, then, is the second iteration of the same show, featuring work from RISD community members with additional local Providence artists. This was the first show I’d seen here that successfully gathered students, alumni, staff, faculty, and the local community together.

To Every Orange Tree started with an impassioned, wide open call for work that dissects imperialism’s many faces and legion of teeth and puts ideas of resistance into practice. The curatorial statement reads: “To Every Orange Tree addresses anti-imperialism and political resistance. It rejects monopoly capitalism, commits to decolonization, and mobilizes toward tangible power.” In addition to curating the exhibition, RSJP activated the gallery space with programs, including a letter-writing workshop with Providence Boycott Divest Sanction (BDS), a documentary screening of Foragers by Jumana Manna with Brown Sunrise, and a teach-in about Black liberation and political art with RISD’s Black Artists and Designers (BAAD).

The show itself asked and maybe even answered some hard-pressed questions: How do we unite branches of anti-imperialist thought? How does art evolve to occupy space? And how does art inspire hope for resistance? Each artist featured in the exhibit is grappling not only with anti-imperial and anti-capitalist themes, but with what it means to be decolonial in their own lives. At times, the works rhyme; at times they contradict in tone. Regardless, by simply being protest art in a gallery space, they evolve the tried and true strategies that art has used to occupy space.

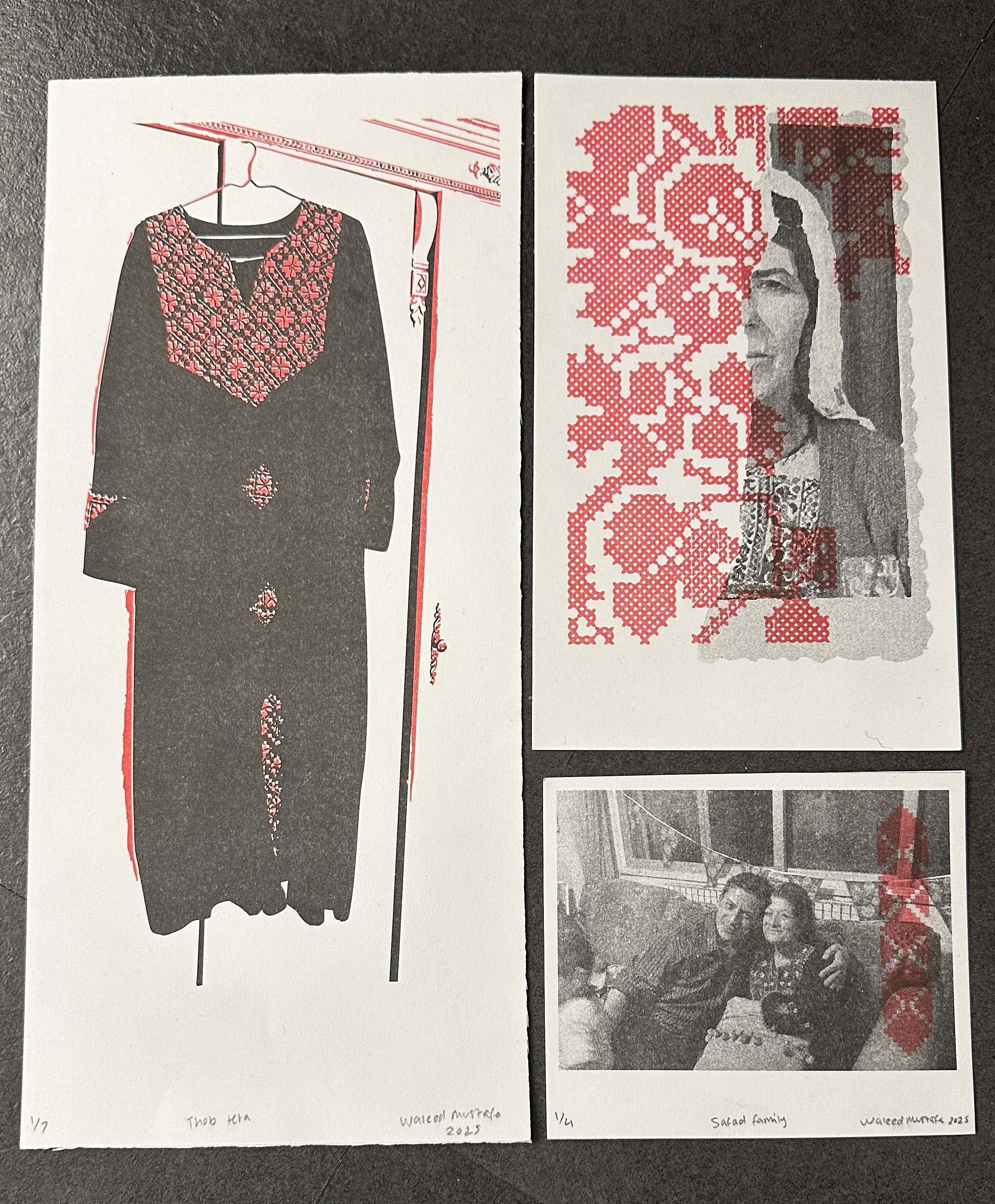

Let’s start with the smallest modules of meaning in this show. Tatreez embroidery patterns are a recurring motif; each pattern, a syllable sounding resilience. In a risograph-printed series, a Palestinian artist collaged portraits of women from their family, overlaid with patterns from the thobes they wore. Behind the scenes, the artist shared tirazain.com/archive with members of RSJP, and the designers took inspiration from this archive for the show’s graphics; for example, the شجرة الحياة (Shajarat Al Hayat Tree of Life) symbol is featured on the program cover. I admire this artist’s generosity in transmitting knowledge so that others can share this collective visual language of unity. These small increments of meaning, repeated and circulated artwork by artwork, accumulate into something that can begin to fill a cultural absence and take up space.

Anonymous, يدها، قصتها (her hands, her story), risograph print on paper

Anonymous, يدها، قصتها (her hands, her story), risograph print on paper Another small, simple piece stood out, with its agitated presence and frank attitude. At once an artwork and a weapon, this piece—a laser-cut brick inscribed with the words “I am not impressed by societies who build their innovations from the blood of the third world,” wants to disturb our comfort as beneficiaries of the Western world. As a literal piece of New England’s colonial and enslavement history, the brick is fraught, and yet it’s tempting to put it in the palm of our hands, arming us with the courage to resist dulling complacency with the promise of cathartic justice. These imperialist powers are, in fact, right on our doorstep.

These two works are among a wall of protest art that encompasses a wide emotional register: from holding space for grief and confusion to incendiary urgency. In posters, a painting, zines, and a decorated denim jacket, the line between “protest art,” a utilitarian instrument, and “political art,” which is more poetic and contemplative, blurs.

Throughout To Every Orange Tree we see different artists negotiate levels of respectability, preserve opacities, and find modes of speaking at volumes that suit their positions, allowing the show itself to strike a balance between the charged and the intimate. And this thread carries on. Just down a corridor, The Fence and The Wall face each other from opposite walls. The Fence calls attention to the illegal blockade built by Israel, here constructed with what the artist calls a “keffiyeh with its fencelike pattern, that also includes birds in flight.” The Wall is a painting inspired by “witnessing the images from the second Intifada and especially the image of Faris Dodeh throwing stones at the tank.”

Anonymous, The Wall, acrylic and mixed media on canvas

Anonymous, The Wall, acrylic and mixed media on canvasThe two artists offer contrasting visual gestures: a glimmer of hope that almost blends in with the fence until it escapes upwards to the sky; and a weighted call to break down and dismantle the wall. The curators shared that the coincidence of the “wall” and the “fence” facing each other across the corridor did not occur to them until opening night.

Another highlight of the exhibition was Lily’s massive charcoal drawing, which was a personal introspection “ on displacement, bureaucracy, and the absurd architectures of belonging.” In the context of the show, the drawing reads as a way to connect her experience of displacement with that of the Palestinian people under Western imperialism. With green cards on legs and migratory creatures absurdly traversing across the drawing, the artist seems to ask: How do we rebuild after displacement and destruction? In this genocide, we’ve grown emotionally desensitized to spectacles of horror through the sheer amount of social media exposure that freeze-frames the victims in perpetual suffering. It feels important, then, to see artists offering their own emotional vulnerability rather than subjecting Palestinians to further visual extraction.

At the center of the exhibition, Joanna’s blanket tapestries embody a comforting speculation on the possible futures of a liberated Palestine. What goes unsaid at first is the stories behind the soft pastels. The artist created the first tapestry to commemorate the “June 2025 Gaza Freedom Flotilla that had Greta Thunberg and 13 other activists on board.” The group was intending to deliver aid to Gaza’s manufactured humanitarian crisis, but was stopped before reaching their destination. The second tapestry is an homage to “farmer Yousef Abu Rabee, who was killed by US-backed Israel in a drone strike near his nursery in October 2024. He had been working towards a degree in agriculture at Al-Azhar University in Gaza City, a university that has now been completely leveled along with every other university in Gaza.” Here we are charged to feel tenderness in the face of unspeakable horrors. This too, is a kind of resistance.

One of the first and last things you’d see in this exhibition is a wall filled with woodcuts, illustrations, and works on paper that feel like artworks you might encounter in everyday life. Activism depends on the circulation and dissemination of information, and it was exhilarating to see the medium of print, long hailed as the pinnacle of Western Enlightenment technologies (think of the Gutenberg Press, for example), appropriated to speak new truths.

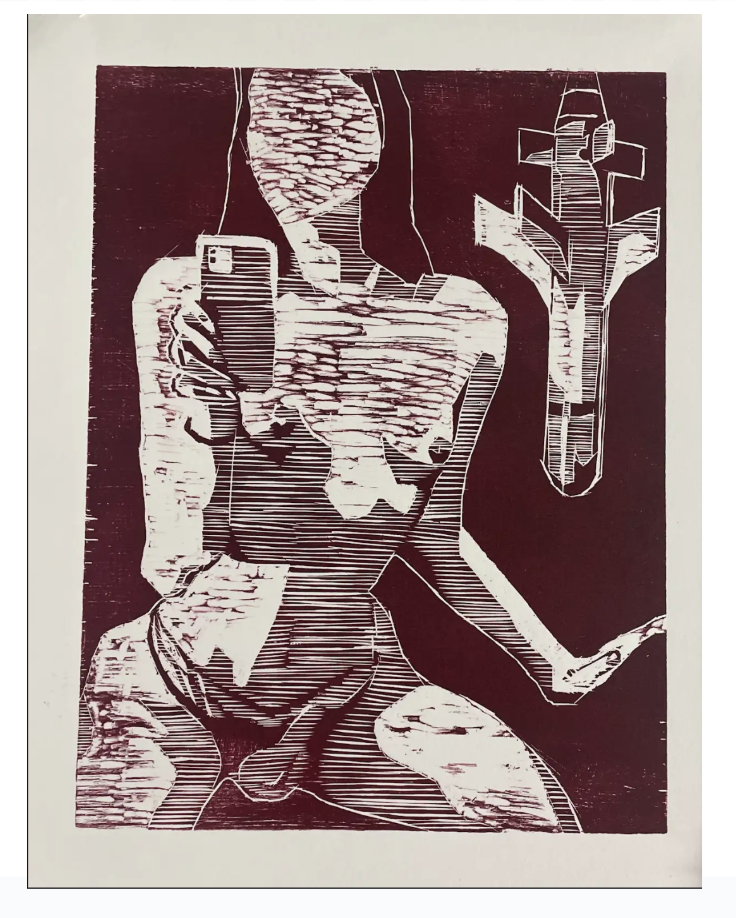

Damiana, Naked truths, woodcut Print on paper

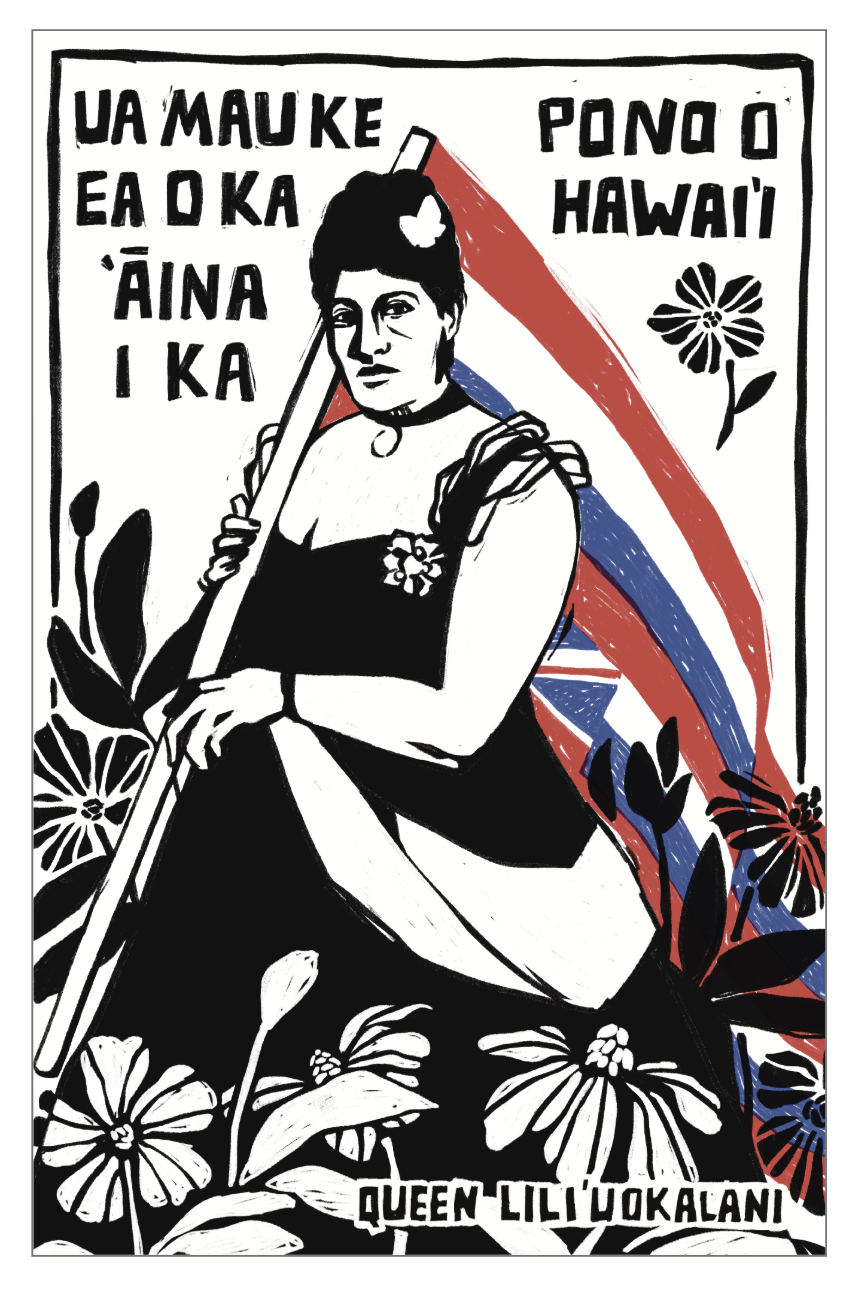

Damiana, Naked truths, woodcut Print on paper Koji, Ua Mau Ke Ea O Ka 'Āina i ka Pono o Hawai'i, print on paper

Koji, Ua Mau Ke Ea O Ka 'Āina i ka Pono o Hawai'i, print on paperIn these prints, we see a coalition of intersectional identity, a call to collective solidarity, and to use rage as a fuel for change. In Naked Truths, Damiana is speaking to a complex set of entanglements when she says: “I’m trying to process how I benefit from the proliferation of this military technology abroad while also being impacted by worsening domestic politics regarding trans women…[in] a political landscape that sees trans bodies as dangerous, predatory, capable of damage like a weapon.” Koji’s print of Queen Liliʻuokalani “holding the Hawaiian Kingdom’s flag upside down to signal a nation in turmoil” and calling for land sovereignty “perpetuated in righteousness” in turn calls for sovereignty for all.

The message throughout this exhibition is loud and clear: the pathway forward to collective liberation is radical hope. In process and in outcome, isn’t there always an inherent hopefulness in making art? There is never a guarantee in getting from point A to point B (or else we’d never make anything at all). But there is the “artist’s belief” that our work will matter when we look back on this chapter of history. I can’t claim to know the exact intentions of these artists, but I know they have touched many people, including myself. As of the time of this article, a fragile ceasefire was reached. Despite this, Israeli airstrike attacks continue in Gaza. The impact we each have is not always perceivable, and that also gives me hope.

In the exhibition, most artists were identified by first name only, and some remained anonymous, as did the author of this review, who couldn’t come up with a pen name.